Robert Tanitch reviews ENO’s Salome at London Coliseum

Oscar Wilde’s pseudo-biblical shocker, gaudy, decadent, vulgar, was written in French in Paris whilst under the heady influence of Flaubert, Moreau, Massenet, Huysmans, Mallarme, Maeterlick and the Symbolist movement.

Wilde didn’t care for either his lover Lord Alfred Douglas’s translation or Aubrey Beardsley’s illustrations which included grotesque and obscene caricatures of himself.

The play got off to a bad start in June 1892, when it was banned in the middle of rehearsals by the Lord Chamberlain who objected to biblical characters appearing on the stage. Sarah Bernhardt, who was to have played Salome, was understandably angry, and Wilde announced he was going to renounce his British citizenship.

Salome has been the plaything of theatre directors, opera directors and film directors ever since. There has been an awful lot of kitsch, including Nazimova’s 1923 silent film, Lindsay Kemp’s 1994 homo-erotic spectacle and Ken Russell’s 1987 film, a vile send-up.

One of the most memorable productions was by Steven Berkoff at the National Theatre in 1989 with himself as Herod. It was acted in languorous slow motion and not only every word but every syllable was clearly enunciated.

The play has been almost totally superseded by Richard Strauss’s opera, first staged in Dresden in 1905 and regularly revived since its British premiere in 1910.

Strauss’s lush, erotic score, awash in its multiple organisms, is as overstated as Wilde’s jewelled and perfumed prose.

ENO’s brochure warns potential audiences that the Australian director Adena Jacobs’ work is noted for questioning patriarchal attitudes with results that are radical, contemporary and feminine.

The production opens with Allison Cook as Salome and Stuart Jackson as Narraboth standing centre stage, roped off and singing in the dark, the least dramatic start imaginable.

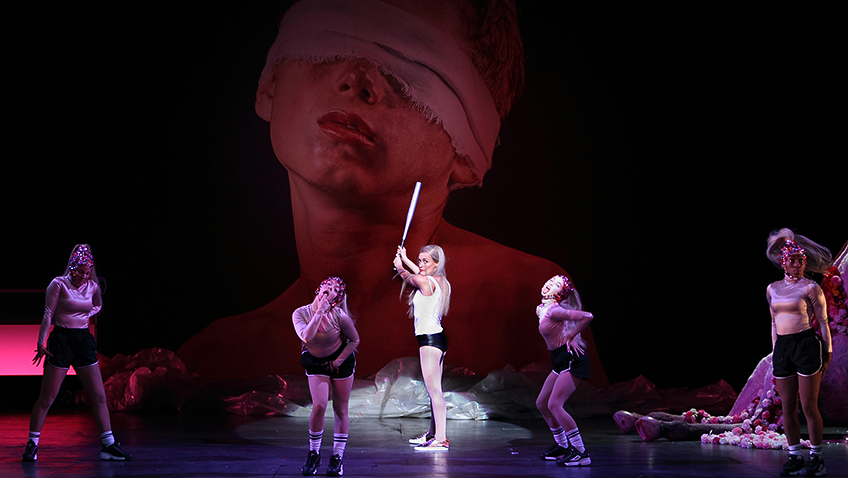

The set is a large empty space. Hanging above the stage and doing distracting gymnastics is a board containing 30 large strip lights in two rows. The back wall is dominated by a giant size photograph of the head of a blindfolded youth. The carcass of a headless horse is dragged on stage and strung up, flowers pouring out of its body.

Jokanaan (aka John the Baptist, impressively sung by David Soar) does not have a cistern for a prison. He is encased in a plastic sheet. He wears underpants and his shoes have stiletto heels. A film of Soar’s mouth in close-up is projected and magnified on to the back wall as he sings. The mouth is rotated to make it look like a vagina.

Michael Colvin’s depraved, frightened, dotty Herod is a comic cartoon. Colvin is also in his underpants. The production and performance undermine the magnificent aria when Herod pleads with Salome to change her mind and ask for anything but the head of Jokanaan.

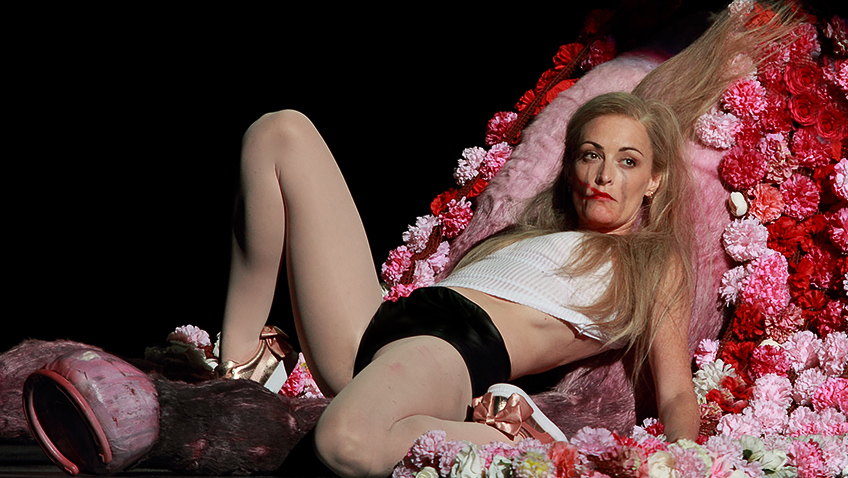

Cook sings with passion; but, like most divas, she does not dance the dance of the seven veils (a Wilde invention). Instead Salome is provided with four cheerleaders to stand in for her and they do some robotic choreography by Melanie Lane which is so appallingly bad you think it should be Lane’s head which should end up on the shining silver platter.

The play ends with Herod ordering his soldiers to kill Salome and they use their shields to crush her to death. Here she shoots herself in the mouth with a revolver.

The play ends with Herod ordering his soldiers to kill Salome and they use their shields to crush her to death. Here she shoots herself in the mouth with a revolver.

The orchestra is conducted by Martyn Brabbins. The music and the singing are so much better than the production.

To learn more about Robert Tanitch and his reviews, click here to go to his website