Dr Ignaz Semmelweiss (1818-1865), the Hungarian surgeon, physicist, scientist, now recognised as a pioneer of antiseptic policy, was unacknowledged in his lifetime and died in a lunatic asylum.

In 1847, twenty years before Louis Pasteur’s findings, he put hygiene first and insisted doctors should wash their hands in chloroform and bed sheets should be changed. In Vienna’s General Hospital in the early 19th century, there was a high mortality rate in the maternity ward run by the doctors and a much lower mortality rate in the maternity ward run by midwives.

After a long investigation, Semmelweis concluded that it was the unseen bacteria, the doctors were carrying from cadaveric contamination in their autopsies, which was killing mothers and their babies. His discovery was rejected by the medical profession who did not want to take the blame for the deaths.

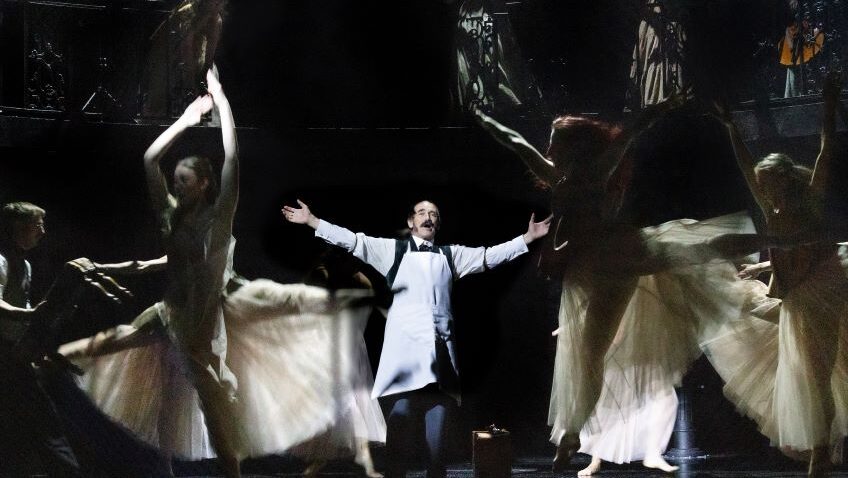

Mark Rylance had the original idea for the play which was written by Stephen Brown with him. The concept was workshopped and directed by Tom Morris, choreographed by Antonia Franceschi and designed by Ti Green. The strength of the production is the atmospheric production itself and its confident inclusion of mime and choreography.

The ballet dancers and string quartet make a considerable contribution. Sometimes they are on stage; sometimes they are on all levels of the auditorium. The dancers represent the spirits of women who had died in childbirth. They also represent Semmelweis’s disturbed mind.

The production’s extra fillip, artistically and commercially, is the sheer presence of Rylance, who gives a riveting performance as the harassed, rejected, ridiculed doctor whose deep flaws in his character, his intolerance, his rude insults and cruel behaviour towards his wife and colleagues, make him a tragic figure.

Alan Williams gives a powerful performance as Johann Klein, the head of the Viennese general hospital, who represents the sexism and ignorance of the male-dominated medical establishment. Pauline Mclynn, no less powerful, is the head midwife, a shrewd woman, who is underestimated because she is a woman. She is appallingly let down by Semmelweis in one of the play’s best and most moving scenes.

To learn more about Robert Tanitch and his reviews, click here to go to his website.

Images courtesy of Simon Annand.