Joyce Glasser reviews The Cordillera of Dreams (October 7, 2022) Cert TBC

A long, imposing aerial view of snow covered mountains, seemingly untouched by civilisation, opens The Cordillera of Dreams, the third in a trilogy of films that bear the hallmark of Chilean filmmaker Patricio Guzmán. For they all contain the now 81-year-old filmmaker’s often profound and always perceptive ruminations on the apparent and subliminal ways in which Chile’s history and unique geography are linked to the Pinochet regime, as a result of this regime, Guzmán became a lifelong exile. All of his films are united by memory and loss.

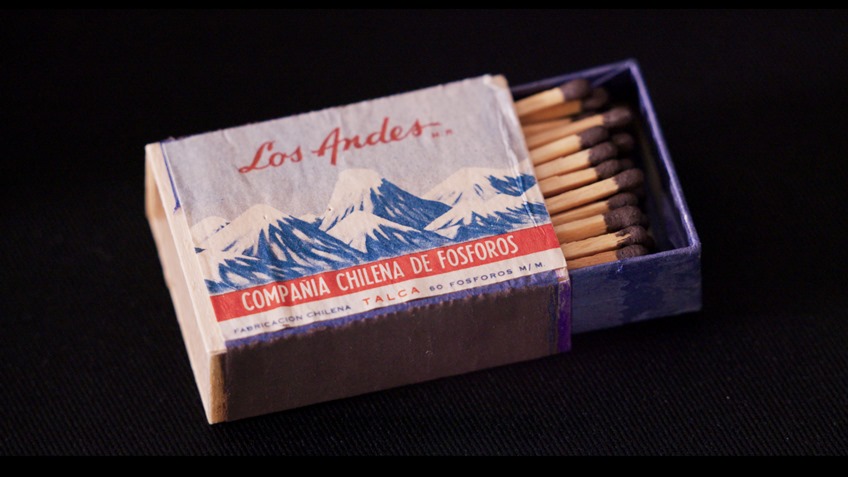

In Nostalgia for the Light (2010) he took us to the Atacama desert in the North where innocent people thought to have opposed the regime were imprisoned and women still search for the bodies of their loved ones. In The Pearl Button (2015) he took us to the extreme Southern coast where indigenous populations were destroyed and where the bodies of innocent people in the late 20th century were dumped in the sea. In The Cordillera of Dreams, Guzmán focuses on the Andes, and in particular, the chain of mountains that forms the “spine” of Santiago and has been, like the desert and the sea, a witness to the horrors inflicted on people who ignore it.

Guzmán was witness to the 1973 overthrow of President Salvador Allende – the world’s first democratically elected Socialist leader – and to the usurpation of the role by the US-backed dictator Augusto Pinochet. More significantly, his filming of the military coup between 1972 and 1973, capturing the violence and resistance, bears irrefutable witness for posterity.

In The Cordillera of Dreams he recalls being herded into the National Football Stadium after the military coup. It has more recently come to light that an unknown number of innocent people were executed in cold blood, with no due process of law in the stadium. Guzmán escaped imprisonment and perhaps death by Pinochet’s forces and smuggled his reels of film to Europe making, between 1975 and 1979 The Battle of Chile. He did not return until a visit in 1996. He has made all his subsequent films in exile (now in France) although they are all about Chile.

Guzmán’s films are intended to show the world what happened and to prevent anyone from forgetting; to hold the country to account for the sake of the future and the innocent dead and disappeared. But upon returning to Chile recently, in which part of this film was made, he does not recognise the city, and feels like his birthplace greets him with indifference. It is during this visit that the significance of the Cordillera, and its metaphoric value, looms large.

‘Most people only see the Cordillera when they are in the Metro,’ he narrates, as we see busy urban commuters rushing by frescoes of the mountain range painted by a friend, Guillermo Muñoz, who now lives in Spain. It seems the inhabitants have turned their backs on the mountains that both protect but also isolate the city.

‘My generation was too busy building a new society to be concerned with the Andes,’ Guzmán says, adding that ‘they might be a gateway to understanding Chile today. ‘ He calls on a number of local artists and sculptors to draw on this hypothesis and they try hard to oblige the prodigal son. Sculptor Francisco Gazitua says, the Cordillera ‘holds the traces of ancestors…20,000 years of traces,’ but does not expand upon that statement. Alvaro Amigo, a Vulcanologist, says, ‘the further you walk, the further back in time you go,’ which is intriguing, but fails to provide a concrete example, or link it to the history of the country in socio-political terms.

Another witness adds that ‘artists must watch over the country’s beauty. The Andes represents 80% of Chilean Territory but it’s abandoned.’ The film ignores the viewpoint that keeping industry and crowds away from nature preserves its pristine beauty, and this environmental stance remains at odds with the notion of abandonment. Unless it is not physical, but metaphysical, poetic and spiritual.

But Guzmán soon makes his point by tracking down the home in which he grew up with happy memories. Amid the skyscrapers that have made the city so foreign to him, in this poorer part of town some dilapidated houses still remain, including the façade of his. The rest of the house is in ruins. This demolition of the city can be seen as a metaphorical erasure of the past, an abandonment of the Pinochet years, that, in the testimony of filmmaker Pablo Salas, has never really changed. The same people hold the power and get richer while the rest of the country is abandoned.

The film then looks at ghost trains transporting Chile’s main source of wealth, copper, past villages with no names in trains with no timetables. Under Allende the copper belonged to the people, but the dictators sold the country to outside investors and now most of it is in private hands, including the export of copper.

‘After I left the Stadium, I left Chile to save my reels,’ Guzmán narrates. ‘Other people kept filming and one was Pablo Salas.’ Yet Salas admits that what he and others filmed represents only 5% of the atrocities. Until Pinochet was arrested in London in 1998, ‘we still didn’t know about the disappeared.’

In his most recent, cramped office Salas shows us his collection of visual testimony. The medium may have changed with technological advances but not the message. He started in 1981 and stopped when Pinochet left, moving to Belgium. He returned in 1994, filming ever since. Only now, ‘the only time you can film properly is when things get rough and there are fewer people,’ as all the crowds with raised arms holding phone cameras make filming difficult. Unfortunately, it is not apparent what Salas is filming today, when Guzmán films Salas on the streets capturing various protests, with no commentary on the issues or the presence of police violence.

In a sombre scene, we see names and incredibly young ages, carved on paving stones taken from rocks in the Cordillera. Guzmán hears the sound of tanks on those stones. Salas says, ‘those responsible have never acknowledged their abuse. They refer to mistakes…but the same people are still in charge.’ With this sentence, British audiences might be reminded of recent politicians referring to ‘mistakes.’

Guzmán ends with a wish: ‘My mother told me that each time a meteorite falls from the sky you make a wish, and if you keep it secret, it comes true’ Guzmán adds: ‘This time I am going to say it out loud. I wish Chile recovers its childhood and its joy.’