Joyce Glasser reviews The Great Escaper (October 6, 2023) Cert. 12A, 96 mins. In cinemas

The idea of old people escaping from retirement homes (80 for Brady), hospitals (The Bucket List) or from overbearing, anxious children (Last Vegas) is a staple for comedies aimed at the boomers, allegedly sympathising with their status as coddled toddlers. The Daily Mail was relying on this cliché with their June 2014 headline, “The Great Escaper” about a Hove nursing home resident and 89-year-old war veteran who took himself to Sword Beach in Normandy in early June. Fortunately, for the double Oscar winners Glenda Jackson and Michael Caine, director Oliver Parker (Dad’s Army) and writer William Ivory (Made in Dagenham) delve behind the headline to deliver a weepie with comic flourishes, touching on trauma and PTSD, survivor’s guilt, heroism, old age and 70-year-love affairs.

Bernard Jordan (Will Fletcher) first saw the Normandy beaches when he was 19, in love with Rene (Laura Marcus) a munitions factory worker who watches the skies and fears for the worst. We are shown their whirlwind love affair in flashbacks that are familiar fare, but almost as engaging as the present day action. When Bernard, called Bernie, returns from the war they marry and have a happy life (although no children are mentioned). Throughout their long marriage, Bernie never discusses his brief acquaintance with a fellow fighter who has haunted him for seventy years.

In 2014 Bernie (Caine) is living in a retirement home in Hove, Sussex, to keep Rene (Jackson) – who has a heart condition – company. When the 70th anniversary of the D-Day landings comes around he realises it is his last chance to return to Normandy. With Rene’s tacit blessing, he departs to make peace with his past.

The care home had tried to book Bernie a place with the British Foreign Legion for the 70th anniversary celebrations but missed the deadline. Undeterred, Bernie simply walks out earlier than usual one morning before breakfast and makes his way to Dover (in reality, it was Portsmouth) where he boards the ferry. Contrary to the eye-catching tabloid headline, Bernie hardly needed to “escape” from the care home where residents, especially those without specific medical conditions, were free to come and go as they pleased.

A young veteran recruited as a marshal to help the delegates, Scott (Victor Oshin) offers to help Bernie boarding, and even jokes that the visibly dazed Bernie get “legless” like Scott to ease the crossing. Bernie recognises in Scott, who lost his leg in Afghanistan, the self-effacing, defensive humour that some veterans use to deal with their injuries and trauma, and later will recognise Scott’s use of transference to avoid confronting his true feelings.

On the ferry from Dover Bernie befriends former RAF Bomber Arthur (John Standing) who admires Bernard’s independence and spirit and spots his medals under his coat. He invites Bernie to share his hotel room and even his tickets to the ceremony with the Queen and President Obama. The relationship between these two veterans has not been written into the script just to give Bernie a sounding board, but to expose a darker side to The Daily Mail headline.

Behind his “together” façade Arthur, a retired English teacher, has also bottled up his grief and although he has health issues, consumes a revealing amount of alcohol. Arthur likes to quote the war poet known for his themes of survivor’s guilt, Charles Causley, a navy seaman from a working-class background whose first collection was entitled Survivors’ Leave. Bernie recognises that Arthur is externalising his own survivor’s guilt after hearing the story of Arthur’s brother, whose plane might have been shot down over Bayeux, possibly by friendly fire from Arthur’s division. Like Bernie, despite their proximity to Northern France, Arthur has never before returned.

In a moving scene, Bernie who has persuaded Arthur to accompany him to Bayeux to pay his respects to his brother, gives their event tickets to a traumatised German veteran who is there to make peace with his past as well. The ceremony, with noble speeches and grateful celebrity heads of state, is not what Bernie or Arthur need.

Instead, the two head to the Commonwealth War Graves in Bayeux where Bernie separates from Arthur to pay his respects to Douglas Bennett (Elliott Norman), a young soldier last seen alive disembarking from the landing craft door that Bernie was operating. His frightened face seeking reassurances appears in Bernie’s reveries (dramatised as intermittent flashbacks which are increasingly coherent).

Meanwhile, back in Hove The Daily Mail story goes viral and the missing resident becomes a celebrity, but Rene is once again worried about her sailor coming home.

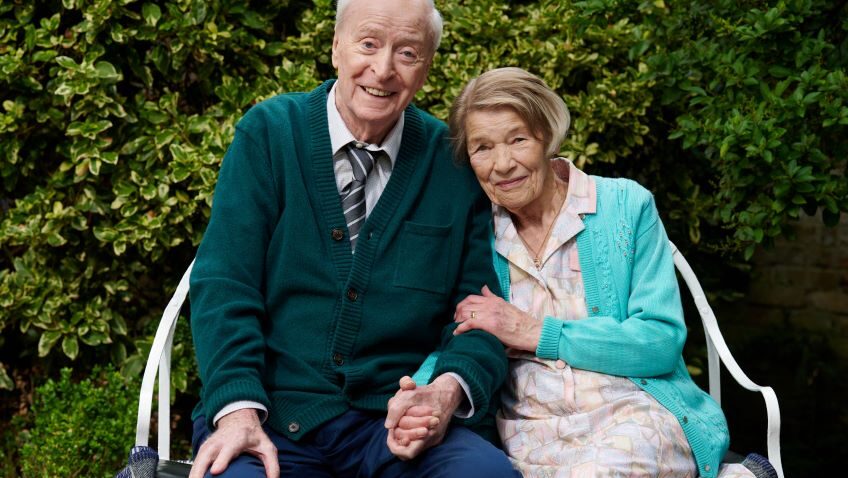

United for the first time in almost fifty years (since Joseph Losey’s The Romantic Englishwoman) Caine and the late Glenda Jackson show that “age shall not weary them, nor the years condemn.” Caine, who was 89, Bernie’s age, at the time of filming, digs deep into his personal experience as a Korean war veteran, and emerges with a totally credible, empathetic character. His and Jackson’s final scene together on the boardwalk will have you in tears, but Parker’s tendency to heavy handedness is kept in check by these two pros and by a script that largely thwarts the anticipated sentimentality or the patronising hackneyed views of older people.

Bernard’s advice to the toadying young veteran Scott is unexpectedly blunt and pungent, to the extent you might think it was an intervention from Caine himself. Surprisingly, it is not Caine who provides the film’s humour, but Jackson whose character reacts to patronising or coddling carers with appropriate cynicism. Ivory supplies Jackson with some good one liners, and she does not disappoint in the delivery. While strong as ever in her dramatic reveries and tender love scenes, Jackson’s comic timing is touted when she provides beauty tips to her nurse Adele (Danielle Vitalis) or answers Adele’s question on how long the doctors give her with: ‘he says I shouldn’t start any long books.’