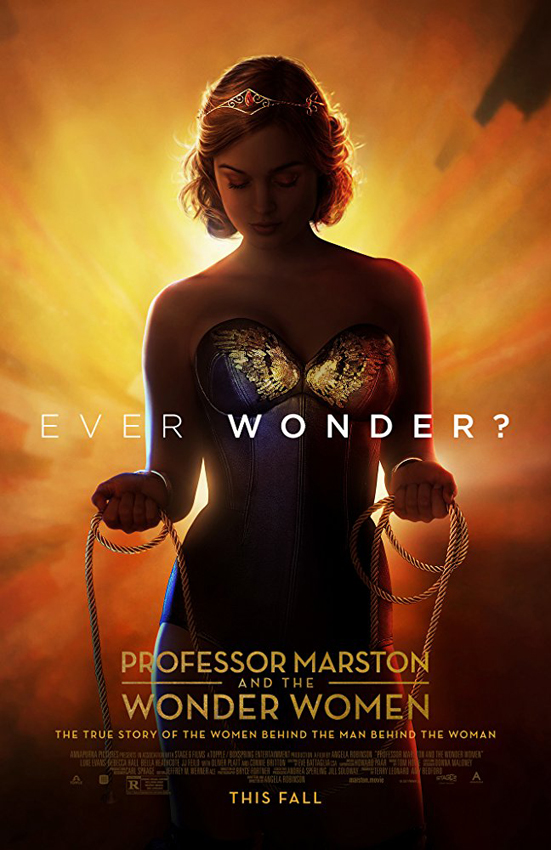

Joyce Glasser reviews Professor Marston and the Wonder Women (November 10, 2017) Cert. 15, 108 min.

Professor Marston and the Wonder Women is a truth-is-stranger-than-fiction, triple biopic of free-thinking rebels: Harvard psychologist, educational consultant and inventor Dr William Moulton Marston and the two women with whom he shared his adult life, cut short in 1947 at age 53. Like Dan Ireland’s romantic tragedy, The Whole Wide World, about Conan the Barbarian creator Robert E Howard, part of the potential appeal is the disconnect between creator and creation. Disappointingly, this disconnect is not exploited and the reality remains more intriguing than is depicted in writer/director Angela Robinson’s lacklustre direction and script.

In 1947 Marston is called to give evidence before a hostile representative of the Child Study Association of America. Robinson uses this interview as a flashback device to tell the story. It is at times disrupting but does provide a way to avoid expository dialogue in filling us in with some of the narrative and Marston’s theories.

In 1947 Marston is called to give evidence before a hostile representative of the Child Study Association of America. Robinson uses this interview as a flashback device to tell the story. It is at times disrupting but does provide a way to avoid expository dialogue in filling us in with some of the narrative and Marston’s theories.

The story begins in 1928 when Marston and his wife, Elizabeth (Rebecca Hall), a feminist with a master’s in psychology from Radcliffe (furious that she cannot get a PhD from Harvard) are teaching at Harvard. Marston is developing his DISC theory of how human emotions operate and how people interrelate. This theory is not used to create any irony in the film, however. More attention is given to Elizabeth and Marston’s experiments with his idea for a lie detector machine. If it is not made clear in the film, Marston is not only a psychologist, but a Harvard Law graduate, hence his particular interest in the polygraph machine.

In need of a teaching assistant, Marston and Elizabeth hire Marston’s pretty student Olive Byrne (Bella Heathcote). Both are impressed that she is the niece of Margaret Sanger, the birth control activist and feminist. It is soon clear, however, that Marston’s interest in Olive is not academic or theoretical.

Despite the liberal nature of her marital relationship, Elizabeth is jealous and prohibits the intimidated Olive from having sex with her husband. But it seems that Olive is more interested in Elizabeth than in Marston. Apparently, Olive’s engagement is just a façade to do what is expected, although there is no evidence from her family of pressure to conform and marry, particularly as Olive is still young. Robinson does not allow the viewer to imagine that both women come together, less out of a hidden attraction to one another than out of a desire to please Marston, who is determined to have both women. A weakness in either the casting or directing is that Marston’s charisma and attraction to women is not immediately (or ever) apparent.

In any event, the three get along a bit too well sexually and pay the cost when they start living together in a ménage à trois (the nature of which is contested by one of Marston’s granddaughter, Christie, who claims the two women were not lovers).

Eventually their private lives become too much for Harvard University and they are sacked. The trio move to a New York suburb where no one knows them. Elizabeth is forced to abandon her studies take up secretarial work and Marston discovers the back rooms of a fetish art shop run by Charles Guyette (JJ Field). It turns out Olive is as turned on as is Marston by a kinky bondage outfit she models. This incident in the shop provides the inspiration for a new comic book (Marston was a consultant to the publisher of what became DC Comics). Marston starts writing a comic book.

For all the promise in this true story, you can sympathise with the complaint of Mrs. Kinsey, wife of the contemporaneous sexologist, that, ‘I hardly see my husband since he took up sex.’ Robinson believes that the sexual exploits of this self-absorbed ménage à trois merit more screen time than does the development of the comics, their impact on audiences and the character development of the three protagonists.

Maybe it would have been more interesting if we were more a part of it. Despite Rebecca Hall’s valiant and quality performance, Robinson’s stilted direction makes it difficult to believe the eroticism felt by any of the parties, none of which is communicated to the audience.

We see Marston trying to sell his idea to Max Gaines (Oliver Platt), the publisher at the National Periodical Publications (DC Comics) who suggests the simplified name Wonder Woman, but it all happens in a flash. There is nothing about the all-important illustrations or the confusion that arose amongst readers between the feminist heroine and Marston’s belief that bondage and submission are part of a respected and noble tradition. He also sold the idea on the basis that this superhero would conquer through love rather than through combat, but if Tina Turner had been reading the comics, she might well ask what love has to do with it.

Ironically for a film about feminists, no one is bothered that Marston is credited with the invention of the lie detector despite Elizabeth and Olive’s key contributions which are actually depicted in the film very explicitly. It is Marston who is inducted into The Comic Book Hall of Fame, although it is quite clearly Olive who came up with the bondage theme and outfit and inspired the comic itself. And it is Elizabeth who told Marston to make his new (male) superhero a woman.

You can watch the film trailer here: