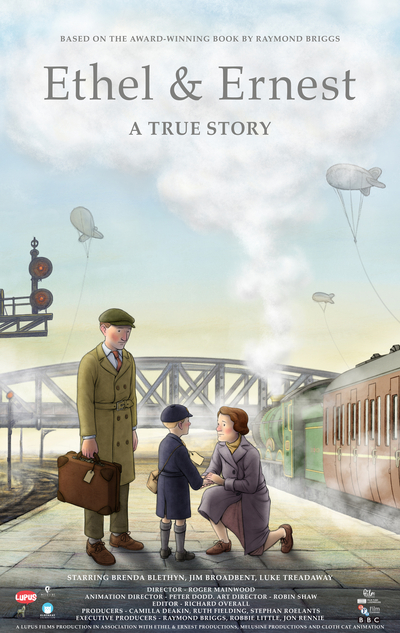

Joyce Glasser reviews Ethel and Ernest (October 28, 2016)

Sensitively decorated by Roger Mainwood, Ethel and Ernest is Raymond Briggs’ (The Snowman) affectionate and beautifully animated tribute to his parents’ 40-year marriage, based on his graphic novel. In inspired casting, Jim Broadbent and Brenda Blethyn give voice to this ordinary couple whose differing attitudes to progress and politics might elicit laughter from the audience, but rarely caused tension within the marriage. The film follows milkman Ernest and housewife Ethel’s personal life against the backdrop of the major trends and events of the 20th century, from their marriage in 1928 until their deaths, in 1971.

Ethel is 33-years-old when they meet (Ernest, 28) and working as a housekeeper to two ladies (‘a ladies’ maid’ as she prefers to call herself). She might have been resigned to a life as yet another single woman in the house when Ernest sails by on his bicycle and waves at the woman in the window. This ritual continues until Ernest presents himself at the door with flowers for their first date. It appears to have been love at first sight. Within no time Ernest is ushering Ethel into their 3-storey terrace house, (mortgaged for £800) and now worth well over a million.

Ethel is 33-years-old when they meet (Ernest, 28) and working as a housekeeper to two ladies (‘a ladies’ maid’ as she prefers to call herself). She might have been resigned to a life as yet another single woman in the house when Ernest sails by on his bicycle and waves at the woman in the window. This ritual continues until Ernest presents himself at the door with flowers for their first date. It appears to have been love at first sight. Within no time Ernest is ushering Ethel into their 3-storey terrace house, (mortgaged for £800) and now worth well over a million.

With Ethel’s sewing and Ernest’s DIY skills, they soon make a comfortable home and can turn to starting the family Ethel longs for. If the babies aren’t coming, the depression is. ‘Two million people unemployed,’ Ernest reads, and then adds, in his characteristic positive, laid back manner, ‘I’m lucky to be a milk man.’

Then one day in 1932- as Ernest announces that Hitler is publishing his book, Mein Kampf here’, Ethel announces the good news. But there are complications with the birth of their son, Raymond, and the doctor declares that given Ethel’s age (she is 38 at the time) there will be no more children.

Most of the dialogue and events in the film are triggered by the device of Ernest reading the paper. From Ethel’s reactions, we immediately learn about their different attitudes to progress (Ernest is progressive) and politics (Ethel has middle-class aspirations) This gives us only a superficial view of the couple and history, there is enough detail to paint a composite picture of three dimensional characters.

Pondering a new article in bed, Ernest says, ‘If you’re a Jew in Germany you are prohibited from marrying a German.’ Ethel, missing the points, replies, ‘I wouldn’t want to marry a German.’ When Ernest reads aloud, ‘Here’s the Duke and Duchess of Windsor shaking hands with Hitler, ‘Ethel replies, ‘Then he couldn’t be all that bad.’ And her reaction to the news of ‘peace with honour (Chamberlain’s misguided ‘appeasement’ strategy in Czechoslovakia) is a naïve, ‘that will be nice.’

But it wasn’t nice, and Hitler and the UK are at war. Ethel and Ernest are soon building an air raid shelter and sending Raymond off to the country. The war years cover a large chunk of the film but contain some real gems. Donating the rest of their metal fence to the war effort, Ernest, a volunteer fire fighter, tells Ethel, ‘they want them for spitfires.’ Ethel replies, ‘Funny thinking of our front gates as spitfires.’

When their house is bombed they visit Raymond in the country, and Ernest confesses that he always wanted a cottage in the country. Upon their return, they deal with the shortages (Ernest: ‘They say we’re supposed to share a bath’/Ethel: ‘Not at the same time!). While news arrives that Hitler is on the run and that it’s safe for Raymond to return to London, Ernest welcomes the advent of social security, affirming, ‘We won!’ Ethel is less sanguine. ‘It’s got to be paid for,’ she retorts, doing the equations instinctively.

With the news that Raymond has been granted a scholarship to a grammar school, social snob Ethel is at last able to brag about her family. Unfortunately, she is unable to pronounce ‘algebra’ when informing a neighbour that he will be doing more than just mathematics. But her dreams of a City job after Oxford for her son suffer a blow when Raymond announces he is dropping grammar school for art school.

With Russia’s explosion of an atomic bomb, and news that the meat ration is being cut, Ethel comments, ‘You can’t blame Hitler now; just your Labour Government.’ The cheery Ernest never seems to argue. You are left to wonder how his life would have turned out with opportunities, family connections or more education.

On a lighter note, Ernest reads about ‘a 26-year-old woman who wants to be an MP,’ and Ethel is frightened to be left alone with the new telephone. Alarmed, she asks, ‘What will I do if it rings when you’re out? ‘To the news, ‘They are legalising homosexuality,’ Ethel asks, ‘What’s that, dear?’

After 37-years service with Royal Arsenal Co-op Society, Ernest retires and Ethel slows down. Ernest is watching the moon landings on their new TV when Ethel asks him to turn it off. This is more than a lack of interest: Ethel is hospitalised and dies. Within months, lonely Ernest has a fatal heart attack.

With so many films focusing on those who are making history, it’s refreshing to have a film about two people who are reacting to it, but without whom society would quickly collapse. At the same time, by contrasting Raymond’s life with his parents’, we can appreciate, in part at least, how education, choice and forward thinking are necessary to improve the world for us all.

You can watch the film trailer here: