Joyce Glasser reviews No Bears (November 11, 2022) Cert 12, 107 mins.

Jafar Panahi is too good a filmmaker to be judged with a handicap, but few other writer-directors have made an award winning career shooting films while awaiting arrest, or an appeal on propaganda charges, or while under a twenty year ban from making films in Iran. Panahi has done more than triumph over adversity by adapting to his dire circumstances. As he sits in his prison cell on a new six year sentence contemplating the release of No Bears, he can say, like the great French poet, Charles Baudelaire, ‘Tu m’as donné ta boue et j’en ai fait de l’or’: (‘you gave me your mud, and I turned it into gold.’)

In his last movie, 3 Faces, Panahi, playing a fictitious version of himself, advises a distraught production manager whose lead actress (Behnaz Jafari) has walked off the set: ‘silver-lining; you’ll find a solution’. Something similar happens at the end of the film Panahi (playing himself) is directing remotely with the help of his production manager Reza (Reza Heydari) who is on location in Turkey. Only, now, it’s Panahi himself who is running out of solutions as the walls close in around him and his parallel love stories cannot end happily.

Situated in the guest room of his landlord, the well-meaning, unctuous Ghanbar (Vahid Mobaseri) and his elderly mother, (Narjes Delaram) in a traditional village just across the border with Turkey, Panahi wants to keep his presence as low key as possible. So does the nervous Ghanbar who climbs on the roof to try to pick up an internet signal. He advises his tenant not to access the roof, or the villagers might suspect he is spying on them.

Watching, seeing and the photos and bits of film that may or may not capture what is seen is a thread that winds through the heart of the film. Photos and film are a record, and they can be taken for truth, to prove an infidelity or, as the exasperated actress portraying Zara will protest, to create a happy ending that is fake. Panahi fans might think of This is not a Film which was smuggled from Iran to the 2011 Cannes Film Festival on a flash drive hidden inside a birthday cake.

No Bears opens on a busy, twisty street in a picturesque town where Zara (Mina Kavani), a waitress in a café, sneaks out to meet her childhood friend Bakhtiar (Bakhtiar Panjei). But the good news he is bringing her backfires. After many years, he has finally purchased a stolen passport which will enable her to travel to Europe as a French woman. When Zara learns that Bakhtiar is still waiting for his own, she tells him she will not leave without him. Who will care for him if he is alone?

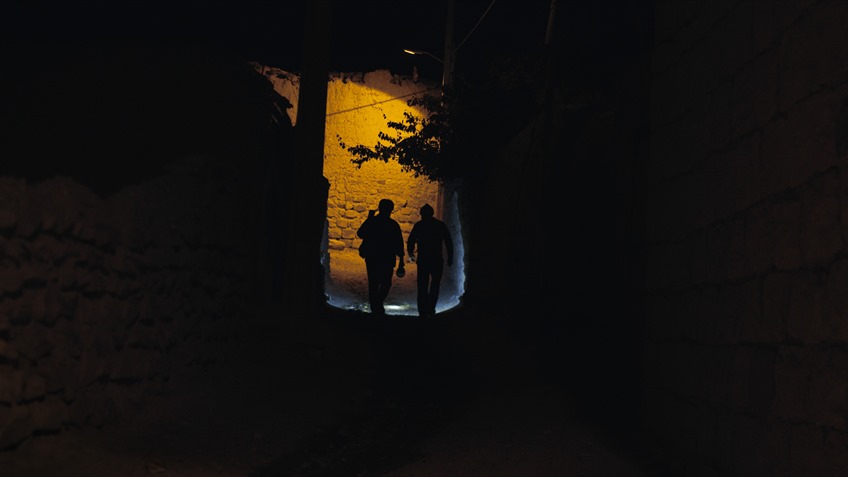

We are jolted out of the scene when Reza appears in camera giving the actress a direction. Then the signal is lost, and we find ourselves, not in the Turkish town where the production is taking place, but in an Iranian village directly across the border where Panahi, watching the filming on his laptop, has lost a signal he was lucky to have had at all. This is a village, purportedly generous and hospitable, that is insulated from the outside world by its location and the superstitions and traditions that bind the small, largely uneducated population.

When Panahi loans Ghanbar his camera to capture a traditional washing of the feet ceremony at an engagement party, he picks up snippets of background sound in which the guests gossip about Ghanbar’s suspicious guest who owns the camera.

Taking a break Panahi goes to take photos of three young boys on a wall. He also takes a few photos of subjects we do not see. Has he inadvertently captured on film Gozal (Darya Alei) and her handsome lover Solduz (Amir Davari)?

In an increasingly ominous subplot, the villagers suspect he has, and it seems every male in the village has a stake in the matter. None more so than the village’s irascible firebrand Jacob (Javad Siyahi) who maintains that when Gozal was born the umbilical cord was cut in his name, betrothing the two from her birth.

The hapless Solduz (who, interestingly, is the only villager to have had some further education) pops up in Panahi’s studio, asking the director to hide the photo for a week, by which time he and Gozal will have eloped. Meanwhile, we return to the location village where Bakhtiar is negotiating to purchase a recently stolen male passport. When he does, he and Zara will finally escape to Europe.

Meanwhile, after being subjected to various attempts to acquire the photo, including an impossibly tense meeting with the duplicitous sheriff (Naser Hashemi), Panahi offers to give his camera drive to the mob to prove he has no such photos. Probably suspecting they would be fooled by technology, they want Panahi instead to swear in a makeshift Sharia court.

But Panahi has other problems. Driven to the border with Reza, he learns that his every move is being watched, not by the government agents, but by smugglers who control the area with the border police’s knowledge. Reza has arrangements with the smugglers and with a Turkish fixer who can get them to Ankara. Panahi resists stepping over that vague line of demarcation in a wasteland on top of a hill.

‘If you are not going to cross the border you should have stayed in Tehran,’ Reza remonstrates. ‘Why come to this place with no internet connection?’ Reza is doing the best he can, but they need the film’s director to take charge. Panahi says he felt it essential to be as close to the shoot as possible, but he won’t cross the border.

Then suddenly, Gozal appears out of nowhere, pleading with Panahi like a prophetess of doom, not to show the picture to anyone or ‘there will be blood.’

The fear that Panahi captures seems real, and it is contagious. We are caught up in what is really a dark thriller taking place in real time. The threat of bears in the borderland might be a way of keeping people from wandering, but there are no bears. There are, however, ancient traditions, outmoded customs and lines in the dirt that serve a similar purpose. We never learn whether the photo of two lovers under the walnut tree exists, but in the end, only the belief that it does matters.