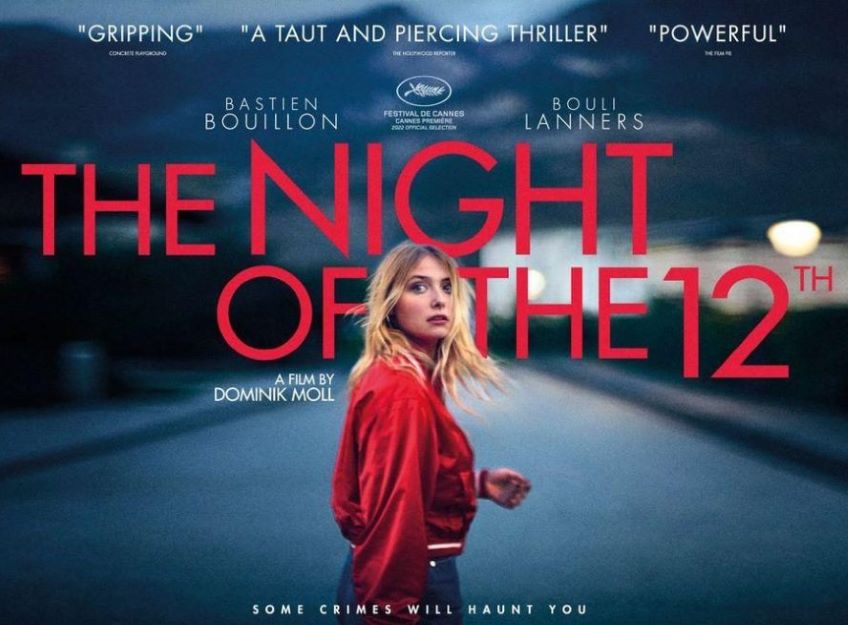

Joyce Glasser reviews The Night of the 12th (March 31, 2023) Cert 15, 115 mins.

French film director, Dominik Moll, who is arguably the greatest master of suspense since Alfred Hitchcock, loses some of the tension that went into Harry, He’s Here to Help, Lemmings and All the Animals in this true-crime police procedural, but not his grip on the audience. And that is despite the spoiler caption telling us that the crime investigation being dramatised is one of the 20% of eight hundred murders a year that remain unsolved in France. But the investigation makes The Night of the 12th strikingly topical, confronting male attitudes to female violence.

The film is based on one section of Pauline Guéna’s thick book 18.3 – une année à la PJ (18.3 – A Year With the Crime Squad). Since the author is a woman writing about the predominantly male world of police who investigate crimes against women, we expect (and this is a criticism of an otherwise powerful film) a heavier emphasis about how male police attitudes affect this particular investigation. The emphasis is instead on the long list of vile suspects that leads the head investigator to conclude that, “there’s something amiss between men and women.”

Changing the location from Paris to Grenoble is a curious decision, particularly when you associate the array of morally bankrupt suspects with all the misfits living in the cracks of large urban populations, but it provides a sense of unease, too, as did the suburban setting of Blue Velvet. Against the grandeur of the French Alps, the mundanity of Grenoble’s sky resorts, and the quiet suburban streets, murder seems incongruous. Young women think nothing about walking home late on their own.

As if foreshadowing the passage of time and the continuity of crime, the film opens with a party celebrating the retirement of Captain Turancheau who departs with his own haunted unsolved case. He formally introduces his replacement: young, affable, controlled and determined Captain Yohan Vivès (Bastien Bouillon, Le Beau Monde) who keeps fit, and sane, by cycling after work in a deserted velodrome.

Later that night, at 3:07am in fact, pretty 21-year-old Clara Royer (Lula Cotton-Frapier) leaves a party for the walk home through middle-class suburban streets. Her friends ask her to stay overnight, then jokingly suspect she is meeting Wesley, her current boyfriend. No, she just feels like going home. Clara pauses to send the hostess, Stéphanie Béguin (Pauline Serieys) nicknamed Nanie, a message telling her what a great friend she is. Suddenly, a soft voice calls her name, stunning her. A look of shock comes over Clara’s face, and she is unable to scream…

Yohan’s men type up their reports from dozens of door-to-door interviews. No one heard or saw anything. The phone has not been removed from the corpse and he calls the last number on it to learn the deceased’s identity and address.

Clara’s parents live in a large, chalet-style house and Yohan freezes when he sees a picture of Clara as a young girl holding a kitten. ‘It’s harder after you’ve seen the corpse,’ says his more seasoned, older partner Marceau (Bouli Lanners, Rust and Bone, Heal the Living). Clara’s mother (Charlene Paul) is too hysterical for questioning. Her father (Matthieu Rozé) explains that while they were close, and Clara lived at home, she did not discuss intimate matters. She seemed to be in love with Wesley Fontana whom she met at work. He seemed to be a nice guy.

A nervous, distraught Stéphanie tells Yohan that while everyone liked Clara, ‘she fell in love too easily.’ What Yohan and Marceau are to learn is that that Stéphanie’s comment, perhaps to protect her misunderstood friend, was a gross understatement.

First up is her “boyfriend” Wesley. His reaction when he learns about her death is not emotional but defensive as he had begun the interview by telling the detectives that ‘she was a nice girl, but I forced myself to date her.’ He explains that he is seeing someone else and thought she was, too. Jules Leroy (Jules Porier) who is 21 and lives with his mother, saw Clara the afternoon of her murder at the climbing gym where he was her instructor. He tells detectives they were no more than “sex friends.” Marceau gets angry at Leroy’s cavalier attitude and shouts: ‘Do you know how Clara died? She was burnt alive!’ Leroy starts giggling uncontrollably.

Then the suspects become really weird. Each is more revolting than the last. If the subject and the acting were not so obviously serious you might mistake this for a pitch black parody of all the CIA type programmes and police procedurals on television. But Moll and his regular co-writer, the brilliant scriptwriter Gilles Marchand, are not interested in the forensics, alibis, evidence, legal issues or why none of the men are charged or tried for murder. Once the viewer hears from these scum, the burning question is why Clara was sexually involved with them – if she was.

We are privy to casual discussions at headquarters, from overtime and the problems with cops getting married, to how women get burnt (Jeanne D’Arc, witches) but men get shot and stabbed. None of the discussions provide much insight into the men’s psychological reactions to the case. Marceau is having a serious mid-life crisis and takes it out on one particularly nasty suspect, but this is more a reaction to his newly pregnant wife’s decision to leave him for another man than it is to the case. Then again, Marceau might blame his long hours and preoccupation with death for the breakup of his marriage. After assaulting the suspect in anger and frustration, Marceau announces he is leaving the force to become a schoolteacher.

Three years have passed. In the second part of the film two significant female characters appear. Nadia (Mouna Soualem) is a sharp new female investigator who replaces Marceau. She talks to Yohan about sexism and racism in the force. The female investigating Judge (Anouk Grinberg) shares Yohan’s concern that his supervisor would not allocate more money for the case. She authorises funds for surveillance of the grave on the third anniversary of Clara’s death, reigniting Yohan’s waning faith in ever finding closure for him, and Clara’s parents.

In the film’s early climactic scene, Yohan is discussing the surveillance with the investigating Judge, and tells her that every cop has a case that “eats him up inside.” The Judge guesses that for Yohan, it’s Clara. ‘Maybe none of them is the killer but each one could have done it… I may be mad, but I believe we won’t find him because all men killed Clara. Something’s amiss between men and women.’ His observation is another gross understatement to round off Stéphanie’s.