Joyce Glasser reviews American Fiction (February 2, 2024) Cert 15, 117 mins.

If the latest spin-off of The Color Purple didn’t have enough problems, along comes the no-holds barred manifesto of Post-Black cinema, American Literature, catapulting this late entry into the Oscar race. It’s a feel-good, comedy-drama with a brain, driven equally by its three-dimensional characters, wit and topical ideas, while being sufficiently provocative and subversively satirical to feel edgy and fresh. And then there’s the added irony – protagonist Monk Ellison would be appalled – that Cord Jefferson’s feature film debut ticks the diversity boxes with a brilliant cast.

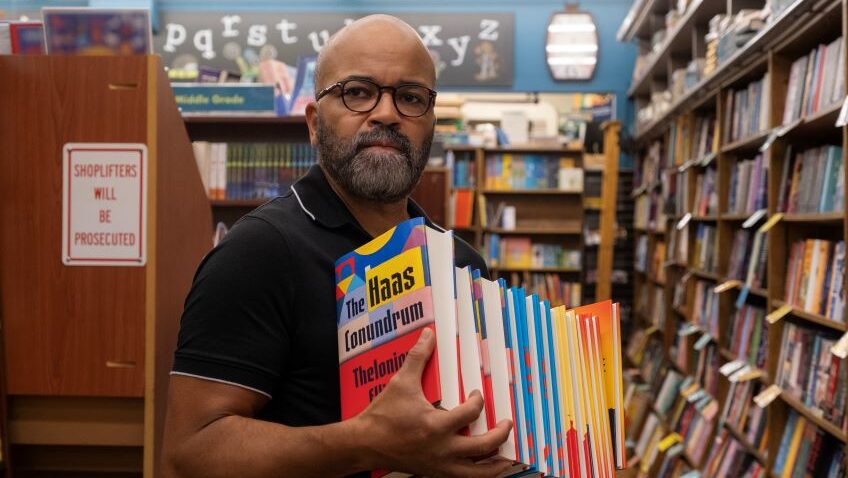

Things are not going well for published author and visiting professor Thelonious “Monk” Ellison (the superb Jeffrey Wright). When we meet him, he being politely invited to take a break after a complaint from a white, green-haired co-ed who cannot accept the word “nigger” that Monk writes on the blackboard in his Literature of the American South class. Monk’s statement that he (an African American), can accept it prompts the offended student to storm out. The discussion of the complaint in the department meeting that follows is a riotous repartee in which Monk justifies his lean output to a pompous, prolific rival.

With a welcome absence of CGI, incomprehensible mumbling, gratuitous nudity and/or sex, violence, big Hollywood names, or a huge budget, this hilarious opening scene is all the set-up we need to settle in for one of the sharpest, most entertaining films of the year. It is quite an accomplishment for a first time feature writer-director and all the more so as his cinematic screenplay is an adaptation of Percival Everett’s (The Trees) complex, multi-layered and literary autobiographical novel Erasure.

After being effectively sacked, Monk is hoping for better news from his publisher. Arthur (John Ortiz) is not optimistic about the sales potential of Monk’s latest: a reworking of Aeschylus’ The Persians. What does Aeschylus have to do with the Black experience? The joke is funny even if you don’t know that Everett’s fourth novel was a retelling the Greek story of Jason and Medea, For Her Dark Skin.

If Monk thinks about race at all, a willingness to pander to the White market’s image of the Black experience looks a lot like racism. Monk undergoes an epiphany when he observes the crowds at the New England Book Festival lapping it up to feel better about themselves. They are passing by Monk’s panel to hear literary sensation Sintara Golden’s reading from her hot new property, We’s Lives in Da Ghetto.

Monk learns that, far from being brought up in the slums, Sintara has a university education and worked as a publisher’s reader, telling an enthralled audience the origin of her first best seller. After reading book after book for the publisher, she asked herself ‘where’s my representation’ and decided to find it in her own book.

If Sintara’s book does not capture her Black experience but a commercialised form of it, Monk’s reaction to her reading harnesses his repressed rage. He goes on the attack in the only way he knows how: sitting behind his desk, writing a pastiche of a “Black book,” a kind of outrageous parody of Richard Wright’s Native Son which he submits to Arthur with the title, “My Pafology.” Arthur is despondent, telling Monk he refuses to circulate the manuscript widely, and does so only with Monk’s pseudonym, Stagg R Leigh to protect his reputation.

Monk decides to leave California for a visit to his estranged family. Although his father is deceased, his mother, Agnes (Leslie Uggams) still lives with their live-in housekeeper Lorraine (Myra Lucretia Taylor) in a large, colonial style home in Boston, although most of the film takes place at the family’s covetable beach house outside of Boston in picturesque, laid-back Scituate. If the film is satirising the White algorithm of what a Black man should be – and yes, a key plot turn in the story is Monk posing as a violent ex-con to conform to a Hollywood producer’s image of him – these locations are significant.

The Ellisons are staunchly middle-class, high achievers, and well educated. They might not fit the Black stereotype, but they fit in to Scituate and even Lorraine finds love with the local cop Maynard (Raymond Anthony Thomas). If Monk is a PhD in literature, his gay, cocaine snorting brother from trendy Tucson, Cliff (an inspired Sterling K. Brown) and his resentfully responsible sister Lisa (Tracee Ellis Ross), who works in a women’s health clinic, are both M.D.s, as was their father. Both siblings have gone through expensive divorces and with Monk out of a job and his take on The Persians rejected, who will pay for Agnes’ expensive care when he and Lisa receive the diagnosis that she has Alzheimer’s.

Director Jefferson navigates his way through the messy family situation with their squabbles, bonding, joys and tragedies without ever losing sight of the main story. These sub-plots work seamlessly to reinforce the central conceit that a Black person’s life is not defined by the White person’s perception of what it should be.

The conceit reaches its apex when, much to Arthur’s surprise, a publisher shows interest in “My Pafology.” Monk’s integrity and conscience react, prompting him to rename the book “FUCK” in order to put an end to his joke. He figures that with that title take it or leave it, even the most liberal, woke publisher will walk away.

This secret double life is a pressure-cooker for Monk, leading to the breakup of a budding relationship with his first Black girlfriend, Coraline (Erika Alexander), a public prosecutor, and to more hilarity when a Hollywood Producer named Wiley (Adam Brody) makes Monk an offer Agnes’s care home bills cannot refuse.

Jeffrey Wright, who is 58, and best known for the miniseries Angels in America, in which he reprised his Broadway role, is no stranger to TV or to the big screen (Shaft, Basquiat), but he may well be remembered for his Oscar-worthy performance here. With Wright leading a perfect cast and a strong female contingent behind the camera, including Christina Dunlap’s score, Jefferson might not have made the definitive film on identity politics, but if there’s a more entertaining one in the wings, bring it on.