Joyce Glasser reviews Mary Cassatt: Painting the Modern Woman (March 8, 2023) Cert U, 94 mins.

What’s “modern” is relative, but there is no better painter to celebrate on International Women’s Day 2023 than the Atlantic Ocean-hopping, ex-pat Impressionist Mary Cassatt. She defied convention to become an artist on her own terms in a man’s world becoming one of only three women in the Impressionist circle, and one of the few American women awarded the Légion d’Honneur for her services to art.

Produced and written by Phil Grabsky and the film’s director, Ali Ray, Mary Cassatt: Painting the Modern Woman is a conventional biodoc, encompassing the range and depth of this unconventional woman and situating her work in the context of her times. Born in 1844 to wealthy parents from distinguished families, she grew up in Philadelphia, then the centre of the American artworld, and travelled to Europe frequently with her parents. By fifteen she renounced the prescribed life of marriage and children which would interfere with her chosen vocation.

Frustrated at the patronising attitude toward women and lack of serious teaching at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts in Philadelphia, after the Civil War, at the age of 21, she went to study in Paris, her mother going along as chaperone. As women were not allowed at the Ecole des Beaux Arts, she began a period of independent study including lessons from the renown Academic painter Jean-Léon Gérôme. Within a year, however, she was living in a rural artists’ colony studying under Manet’s teacher, Thomas Couture.

Since most of the submissions from the Avant Garde painters (the would be Impressionists) were rejected at the Official Salon – where any painter hoping to be sold had to display – in 1863 Napoleon III founded the Salon des Refusés. It is here that Édouard Manet’s Déjeuner sur l’herbe and James McNeill Whistler’s Symphony in White, No. 1: The White Girl were first shown and greeted with ridicule. Cassatt was still entering her paintings in the Official Salon, where the stream of rejections was broken by A Mandolin Player, one of only two paintings by a woman shown in the Salon of 1868.

During the Franco-Prussian War Cassatt returned to the USA, trying her luck in Chicago where a few of her paintings were exhibited – before being destroyed in the Great Chicago Fire of 1871. Then, through a contact, she landed a commission that changed her life and the history of art. She returned to Europe with an American painter friend, on a paid commission from the Catholic Bishop of Pittsburgh to copy a famous Correggio Madonna and Child in Parma Italy. Cassatt then embarked on a grand tour of Italy and Spain, copying the great masters, but always giving her paintings a twist, honing in on her female model’s psychological depth.

One example is On the Balcony of 1873, showing the influence of a Spanish genre painting. Two women are on a balcony in a tight space with a dashing man in a wide hat towering over them half in shadow. The balcony might be a nod to Manet’s 1868 The Balcony, but there is an awkwardness in the arrangement, creating a tension between the overbearing man and the two women.

If Cassatt only painted women it was not only because copying male figures in the Louvre was the only substitute for live drawing classes. Cassatt considered the women in her circle worthy subjects. The men around her painted women – sleeping, bathing, at their toilettes and with children: Cassatt painted these scenes with more authenticity, treating these routine actions as such without objectifying the women or sentimentalising the acts. Her children are as real as is their bond with their mothers: Girl in a Blue Chair shows a bored, perhaps petulant, little girl plopped on a chair staring into space, her petticoat showing, her legs hanging unladylike.

Her women are thinking individuals with inner lives, intelligence and psychological depth: they work diligently like men, even if they work at domestic jobs like sewing or operating a loom, such as Lydia at the Cord (1880). Another painting shows Lydia (by this point, her pretty sister and their parents had moved to Paris to support Mary) driving a horse and carriage with the male groom with his back to us, idle. In Reading the Figaro of 1878, an intelligent, strong-minded, older woman in glasses (the artist’s mother) assiduously reads the eponymous serious newspaper.

Cassatt admired Degas’s ballet dancers before she met him, and he, struck by her talent, called her a “kindred spirit.” When they finally met in 1878, he became a mentor, collaborator and colleague, persuading her to abandon the official Salon to exhibit in what would become eight Impressionist Exhibitions from 1974 to 1886.

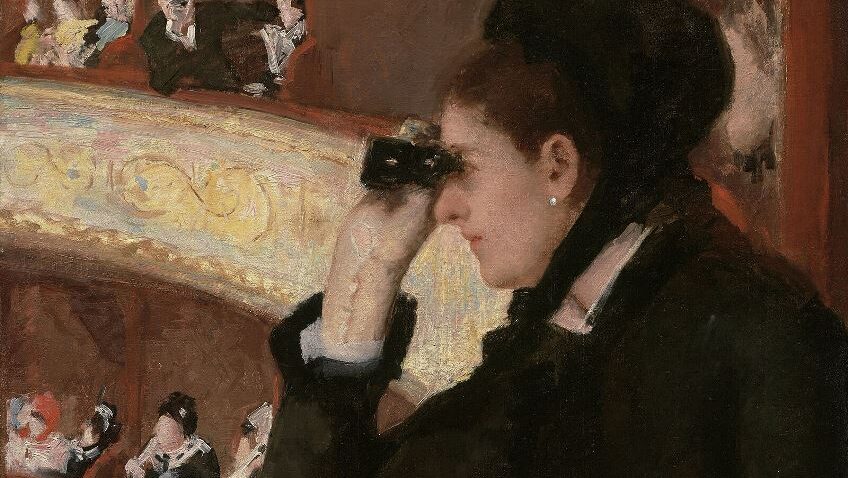

Like Degas, Manet and Walter Sickert she frequented the newly built theatres and opera house where people went to see as well as be seen. The difference is that in The Loge (1878), for example, at the interval, a woman with binoculars is watching someone oblivious to the surveillance of a man in the adjacent box. A young woman with a pearl necklace darts a joyous smile across the balcony at an unseen person, an emotion rarely painted by male artists.

When Japanism was all the rage, Cassatt was at the forefront, armed with printmaking skills she developed with Degas. A shrewd judge of the marketplace, she created a series of ten stunning, Japanese influenced etchings with aquatint showing everyday scenes of women at home. Although she sold them bundled in a pack of ten, making a purchase more expensive, they were a big hit.

When the French art market was down in the early 1880s, Cassatt helped her dealer, Paul Durand-Ruel, avoid bankruptcy by opening the Impressionist market in the USA. Later she was instrumental in advising wealthy collectors and museums in the USA how to build their collections, using her connections to hook up buyers in America with her colleagues in France.

Once written off as a sentimental Woman and Child at the National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C. is a striking painting of a red-head with a huge sunflower on her dress, holding up a mirror to her toddler daughter, as though showing her the future. Then art historian Nicole Georgopulos pointed out that in 1895 The National American Woman Suffrage Association had adopted the Sunflower as their symbol, and the painting was retitled The Woman with the Sunflower. In 1915, eleven years before her death at 82, Cassatt donated the proceeds of the sale of many works in her collection to an exhibition organised by her American friend, Louisine Havemeyer, a philanthropist, collector and ardent suffragette.