Joyce Glasser reviews Rock Hudson: All that Heaven Allowed (Available on Digital Platforms from October 23, 2023). Cert 15, 106 mins.

That Stephen Kijak’s thorough and engrossing biographical documentary (or bio-doc) devotes more time to Rock Hudson’s personal life than to his films is apparent from the clever title. It refers to Douglas Sirk’s ground-breaking film All that Heaven Allows about a wealthy, suburban housewife’s affair with her gardener, a role that confirmed Hudson’s image as a heartthrob for frustrated, trapped 1950s housewives the world over. Hudson’s lovers, agent, close friends, many leading ladies and ultimately even, for a time, his token wife, guarded the secret that he was acting against type, a secret that was out of the bag by the time he died of AIDS, in 1985. A product of the Hollywood studio system that was disappearing by the time of his death, Hudson felt fortunate and was grateful for his career and that the film studios took care of everything, leaving him to focus on acting. But this heaven did not allow deviance from societal values and condemned him to live a dual life.

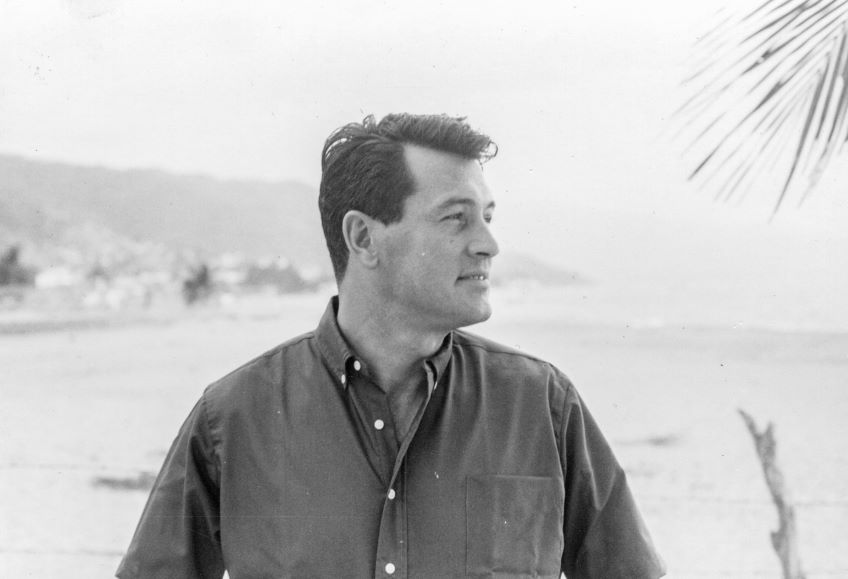

Born Roy Harold Scherer Jr in a small, midwestern town during the Great Depression, Roy’s parents divorced when he was four and his father disappeared. His mother remarried a man Roy despised who forced the boy to take the surname, Fitzgerald, but that marriage, too, ended in divorce. Young Roy had to work and had no time for extracurricular activities, but one of his jobs was an usher in the local cinema and he wondered about acting. His initial attempts were thwarted because he couldn’t remember his lines. In 1943 he enlisted in the Navy, and by 1946, he decided, ‘now is the time to do what you want to do.’

What he wanted to do was act. He went to Los Angeles where the only person he knew was his estranged father. Through a Navy buddy he met Ken Hodge, a radio producer with lots of contacts who invited Roy to live with him in Long Beach and the two became close. Ken, apparently smitten by Roy, helped him find a job by sending out photos to agents and studios. There was only one reply: from Henry Willson.

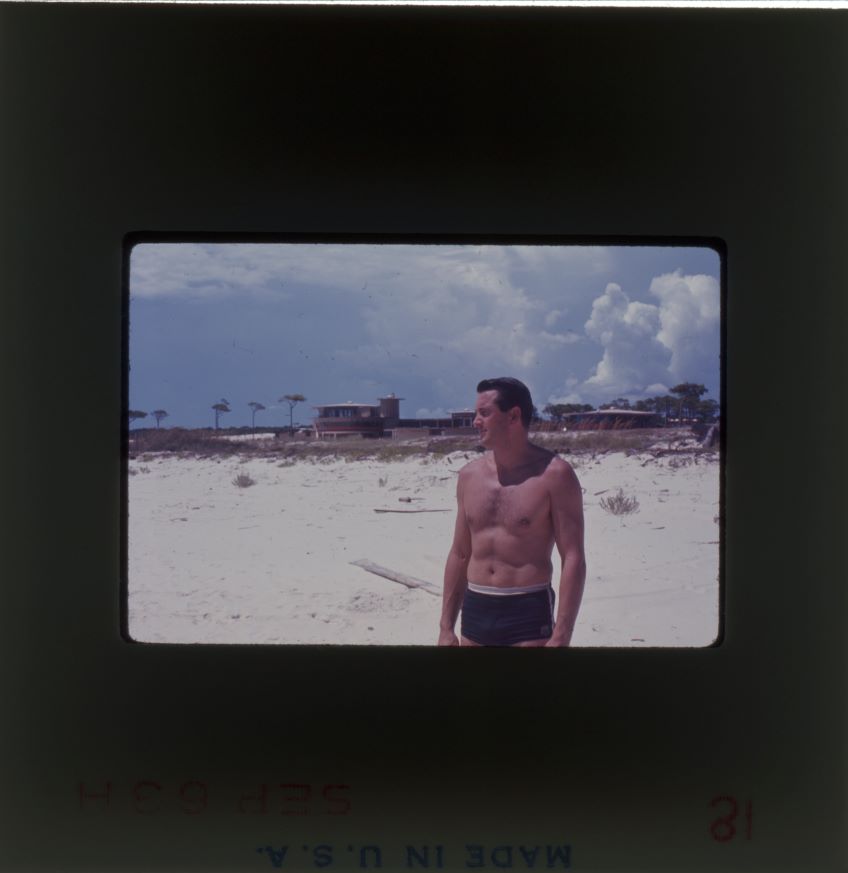

Willson headed David O Selznick’s talent department in 1943, just after he finished Gone with the Wind. The silent stars were often too effeminate for post war films that were influenced by all the patriotic photos of sailors and soldiers with their shirts off. Willson, who went on to form his own talent agency, cornered the market on beefy boys out of the armed services. He created the “beefcake craze”, with clients like Tab Hunter, Robert Wagner, John Derek, Doug McClure and Troy Donahue.

Hudson, as he now was, did not want to be a beefcake, but an actor, and enrolled in classes, seizing every opportunity to obtain training. Willson also taught his protégés something: how to be heterosexual and sexy in a masculine way. Willson, a sexual predator, exacted a price for his services. The first thing Willson had Roy do was change his name. The second was to write “Mr Hodge” an abrupt goodbye letter.

Because Hudson, one of the last actors to be coddled and corralled by the studio system, was very tall, dark and wholesomely handsome, he was cast first in macho roles in inexpensive adventure films for Universal. Selznick, who by then had his own company, never believed that Hudson had any real talent. As well as a few gangster films and Westerns, Hudson contributed to feeding the hunger for war films in the early 1950s. His early credited titles include, Gun Fury, Winchester ’73, Desert Hawk, Air Cadet, and A Bend in the River.

Then came a couple of lucky breaks in the form of the actor-turned successful producer Ross Hunter, and Hans Detlef Sierck, a German refugee who, like Hunter and Hudson, changed his name to the more all American Douglas Sirk. Sirk, who first directed Hudson in Has Anybody Seen My Gal remembers Jimmy Dean, playing a troublesome customer at the soda fountain where Hudson is a waiter, and “nobody paid any attention to him.” Sirk thought Dean was the better actor.

Hunter wanted to put romance and glamour back into Hollywood and cast Hudson opposite Jane Wyman in Magnificent Obsession (1954) which became Universal’s biggest money maker to date. Until the comedies with Doris Day, Hudson became the actor to call for glossy, romantic melodramas, and the formula paid dividends. The following year, Sirk, Hunter and Hudson made All That Heaven Allows and Hudson was given an identity that he played for the rest of his life.

Meanwhile, the fan magazines were curious about Hudson sharing a house with Bob Preble (Willson’s idea) and why nothing came of Hudson’s friendship with his friend, the script supervisor Betty Abbott. Willson’s job was to keep Hudson’s personal life private. When Confidential Magazine threatened to reveal Hudson’s homosexuality, Willson’s enlisted his secretary Phyllis Gates to play Mrs Rock Hudson. The marriage was real, but everything else, including an exotic honeymoon, was scripted.

Soon after the marriage Hudson was reunited with Jimmy Dean in Giant, but now Dean was a rising star and there was tension on the set. Nonetheless, Hudson loved working with co-star Elizabeth Taylor who, when Hudson contracted AIDS, began her long commitment to raising money for AIDS research and charities.

In 1959, a year after the three-year marriage ended, Hunter cast Hudson opposite Doris Day in Pillow Talk. The sham marriage was temporarily forgotten in the face of this huge hit that showed Hudson could do both melodrama and romantic comedy.

The film races through Hudson’s later years, where he continued to get roles in films and television. By the late 1960s his star was waning as edgy films with anti-heroes, and, ironically, homosexual overtones, like Midnight Cowboy and Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid were emerging. He was drinking heavily and chain smoking and in 1981, a heart attack curtailed his career. Hudson was thrown a lifeline with a role in the hit series, Dynasty, but by then AIDS had taken its toll. Linda Evans tells a harrowing story of the scene where the two are supposed to kiss and how friends were afraid to come over to her house after filming with Hudson.

In the second half of the film the narrative is juxtaposed with a series of on-screen interviews with openly gay lovers such as Tales of the City author Armistead Maupin. These accounts paint a somewhat sad picture of the star. Prevented from forming a lasting partnership, he engaged a contact to round up handsome boys for his wild pool parties. Less insightful, albeit fascinating, is Kijak’s tendency to insert clips that apparently show a more subversive side of the films that escaped the censors, although these are frustratingly shown out of context and are not captioned.