Joyce Glasser reviews The Quiet Girl (May 13, 2022) Cert. 12A, 94 mins.

Colm Bairéad’s feature film debut, The Quiet Girl is easy to overlook. In common with its eponymous protagonist, it is a quiet and delicately paced without a famous cast. That it does not have much of a plot and is in the Gaelic language with subtitles might not be an initial selling point either, although the unfamiliar cast and Gaelic language enhance the story, set in rural Ireland, circa 1980.

To overlook The Quiet Girl would be to underestimate one of the hardest jobs a director can give himself: dramatising the evolution of the relationships between three people over a summer season and making you care about the outcome.

Adapting his script from Claire Keegan’s short story Foster, Bairéad extracts tension and emotional catharsis from this restraint and rewards you at the end with an emotional punch that is hard to shake off.

That’s not to say the film is perfect, but the big flaw occurs in the first ten minutes. Little Cáit (Catherine Clinch), who is unhappy in her dysfunctional home life and at school, reacts by retreating within herself. She barely talks and does not seem to have friends. The thin, pretty little girl in the hand-me-down dress, shares a ramshackle farmhouse with her continually pregnant, exhausted mother (Kate Nic Chonaonaigh), her alcoholic, gambling, good-for-nothing father (Michael Patric), and siblings she does not relate to. Cáit is eight or nine and still wets the bed.

The house is spartan with no creature comforts. A meal is slices of bread. The hay has not been harvested and the new baby will be born at the same time as the new calf. Something has to go, and it’s Cáit, who will spend the summer with her mother’s childless cousin, Eibhlin (Carrie Crowley) and her husband Sean Kinsella (Andrew Bennett).

Trapped in this familiar, misery porn setting you might want to head for the exit, but resist, for it is this set up that makes what follows so welcome.

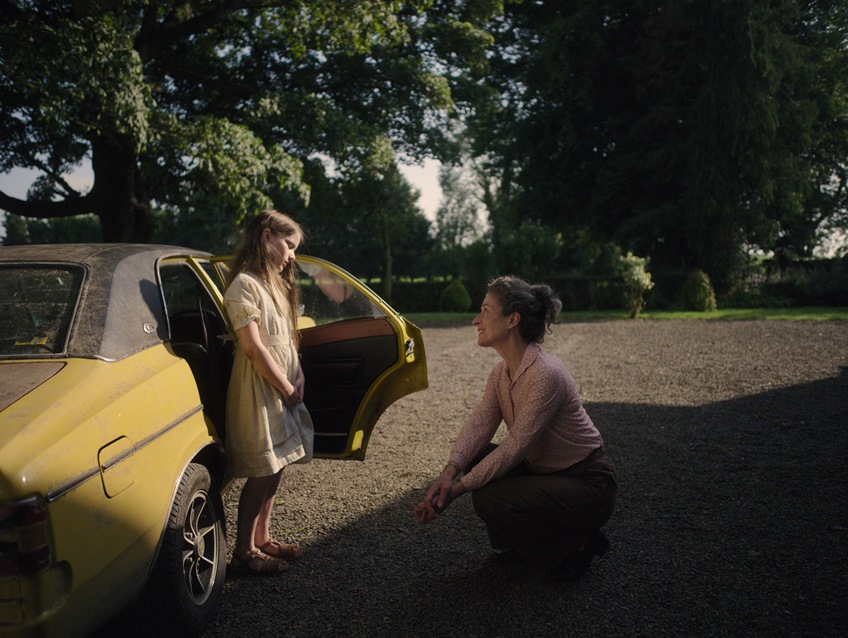

After a tedious, hot, silent, journey with her gruff, morose father, Cáit arrives at a beautiful, immaculate, old stone farmhouse and a warm welcome from Eibhlin. You can tell the couple are uncomfortable with the father who lacks any semblance of social graces. Eibhlin is appalled by his conduct at dinner when he puts a cigarette out on his plate and does not even say goodbye to his daughter.

Eibhlin realises, too late, that he left with Cáit’s suitcase in the boot of his car, and she begins to worry about her cousin, living with such a brute. When she asks Cáit why the hay was late, Cáit guilelessly replies that her mother did not have the money to pay the hired hands to harvest it. Eibhlin can only guess where the money went. ‘God help you,’ she mumbles spontaneously. ‘If you were mine, I would never leave you in a house with strangers.’

But in this case, it turns out to be the best thing that ever happened to Cáit.

That said, she is wary when she realises there are no children in the house. Cáit has never been the centre of attention and has never known such peace and quiet. We gradually become aware, too, when Eibhlin makes the mistake of leaving Cáit with the community busybody, that the couple are outcasts like Cáit – and the subject of two-faced gossip. The simple premise expands as we start to focus on the vulnerability and loneliness of the adult couple, and not just their ward.

Eibhlin is a tactile woman, a bit too doting, perhaps, and we soon suspect why. She combs Cáit’s hair slowly and rhythmically like a kind of therapy, but for whom? And Eibhlin watches as Cáit cautiously steps into the steaming bathtub as though it were a tidal pool, happy to be able to offer the girl this little luxury.

Water becomes important again when Eibhlin takes Cáit to the well, a place that gives life, and a place of danger and death. ‘There are no secrets in this house’ Eibhlin tells Cáit. ‘If there are secrets, there’s shame.’

But in fact there is a big secret in the house. There are clues the audience will detect, but Cáit does not. During her first night in the strange house, sleeping in her own room for the first time in her life, her eyes, and ours, land on the old wallpaper decorated with miniature trains. And since Cáit is left with nothing to wear after her father’s carelessness, Eibhlin brings some old clothes from the closet. Although they seem to fit the child, which is surprising, they appear to be boy’s clothes.

While meals are healthy and regular, and Cáit enjoys helping Eibhlin with the cooking, Sean remains distant and reserved. After he expresses irritation when Cáit goes to Church in the boyish clothing, Eibhlin takes her shopping, and she has her first brand new, stylish clothing.

Due to misread signals, Cáit’s first time alone with Sean is a disaster. When she wanders off in the barn, Sean becomes alarmed and goes looking for her, frantic that she has had a accident on his watch. Cáit interprets his panic as anger, and she recoils.

The next time, though, Cáit makes an effort to be useful in the barn, observing Sean’s tasks and following them. And gradually Cáit notices signs of a rapprochement: a biscuit left on the table, a reward, a symbol. Soon there are ice-creams and days out that most children take for granted.

One day Sean asks Cáit to run to the post box at the end of a long, tree-lined lane between the property and the road. He is impressed with her speed, and she basks in the praise. This daily task becomes a routine with Sean timing her. The camera focuses on Cáit’s face as she runs with abandon, and a smile on her face. This motif returns at the end of the film so poetically and cathartically that the depth of emotion will transport you.