Gripping, alive and immediate, Opera North’s handsome production of Handel’s handsome oratorio, Susanna, performed in a fourth collaboration with The Phoenix Dance Company, is stunning. An oratorio it may be but banish visions of static rows of black-clad singers and soloists, standing singing bible stories into the air. This fully enacted stage drama is powerfully moving in all senses of the word. Fine singing and orchestral playing are just the start. The full impact and immediacy of the drama, both physically and emotionally, spring from all-round convincing, superbly integrated acting, including from every member of the vast chorus, and from strong chemistry between characters, while dancers serve to highlight emotions still further at certain moments.

Susanna, first performed in 1749 – seven years after the premiere of Handel’s Messiah and with echoes of that work in places – is based on a story in chapter 13 of the Bible’s Book of Daniel that tells how, when her loving husband Joacim is away, loyal, virtuous wife, Susanna, is approached by a couple of lecherous, old elders as she’s quietly bathing. Her total rejection of their persistent, nasty advances makes them so angrily vengeful they accuse her of adultery, a crime punishable by death. Enter now young Daniel to expose their lies, clear her name and save her from execution. So, it turns out better than it might have done, though this production clearly suggests that lasting trauma isn’t so easily brushed aside and forgotten. Of course, corrupt, deceitful men of power who abuse women don’t crop up only in Bible stories: they were there in Handel’s day, too, and they’re still here today in ours, similar stories and scenarios playing out repeatedly the world over. In addressing these evergreen issues of injustice and violence against women, Opera North sets the story closer to our own time.

Loose, era-non-specific garments in muted greys, earthy browns, cream and dark blue predominate, with silvery satin tops for dancers, all the costumes of characters, dancers and chorus merging and blending. The men’s smart, grey or blue suits and briefcases and the initial silvery outfit of silver-blond Susanna might, though, evoke hints of the 1980s. Green and red feature in the costumes of Daniel (sung in fine style by much appreciated soprano Claire Lees) and his/her dancing counterpart, while worthy Joacim’s shirt is white as are various veils and floaty or satin garments worn by the determinedly chaste Susanna. Once her virtue is besmirched, though, the fickle, vindictive crowd plaster these in filthy, black handprints, and black confetti rains down on her in contrast to the white confetti showers that poured on her as she bathed.

Leaving maximum, uncluttered floor-space for dancers and for several full-chorus scenes, the clean-lined set, predominantly in shades of grey, offers action on two levels with a long, frame-edged balcony accessed by two stairways, and a branching, creeping vine to one side that reaches across above, ready to be leapt upon by a singing Joacim or have its light-bulbs occasionally lit. A series of smoky-opaque, mobile screens prove usefully versatile, spookily effective as shower screens for the grotesquely lascivious elders to lurk along behind to ogle, then accost, Susanna as she luxuriates in her sparklingly shiny, pure white bathtub.

Handel (1685-1759) was German by birth, of course, but came over on a big boat (we assume) to settle in London in 1712, dropping his umlaut and becoming a British citizen in 1727 and subsequently one of Britain’s foremost composers. The libretto, probably by Moses Mendes, full of uplifting, bucolic and divine references and repeated words, is sung in English with BSL and mime integrated (sort of) into onstage action by Tianah Hodding. Under the debut direction of harpsichord-playing Johanna Soller, The Orchestra of Opera North, conjures up beautifully Handel’s distinctive, baroque warmth, bringing both lightness and power to its wealth of tripping trills, twirls, fugal overlays and mile-long melismas that run through the melodic, harmonic blends of instruments and voices with forthright, assertive fervour. As voices ring out, oboes, trumpets, bassoon and copious strings are underpinned with the simple, comfortable orderliness of continuo from harpsichords, organ and theorbo.

Soprano Anna Dennis’s portrayal of Susanna as strong yet tender is staggeringly good. We believe in her all the way as her emotions undergo realistic changes as events take over. Her acting and expressive solos engage and move us as she gives a more modern take on how she’s affected by her ordeal even after she’s vindicated of charges and her husband returns from his business trip. The joyous words of triumph and praise from the crowd imply an instant happy ever after, but her reactions demonstrate it’s not that simple: trauma has lasting effects. One updated reaction comes when, putting aside her customary integrity for a few minutes, Susanna thoroughly humiliates her assailants, even kicking one of them where it hurts the most.

Meanwhile, James Hall is magnificent as warm and tender Joacim, his physical and emotional acting, stupendous countertenor singing and mellifluous flow of melismas spine-tingling at times. He embodies Joacim magnificently and the chemistry between him and Susanna is tremendous, their many solos and duets a delight. Matthew Brook, in blue suit and white beard, is convincing, too, as Susanna’s kindly, devoted father, Chelsias, though some notes are challengingly low for his bass range. Also excellent for their engaging character portrayals and solo singing are Colin Judson and Karl Huml as the Elders and Amy Freston as Susanna’s Attendant, while the full chorus, onstage several times, is magnificent not only in delivering the powerful choruses, but also in fully integrating credibility and expressive movement into their enacted roles. The menace in their warning as they move forward to eyeball the audience and confront them with the facts that, ‘His bolt shall quickly fly’, and ’Wrath Divine outstrips the wind’ is so intense it’s impossible not to believe them.

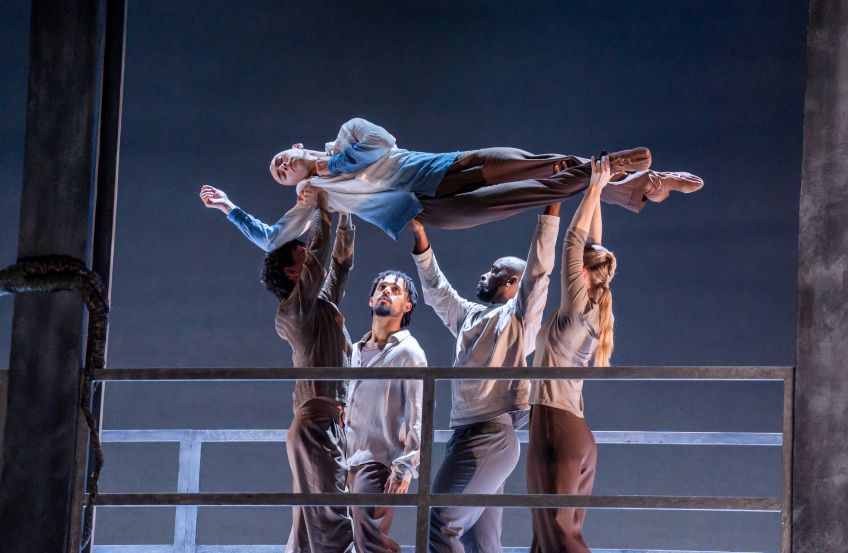

Into this rich mix comes yet another layer as nine dancers merge and interact in the drama, often as different versions of the characters. At times it’s frustratingly much too much to try and keep one pair of ears and eyes simultaneously focused on music, on expressions and interactions of characters and on dancers, especially if they’re performing, literally and metaphorically, on two different levels, or if the dance becomes so distractingly busy it detracts from the main drama; when a dancer unexpectedly pops up from Susanna’s apparently empty bath, laughter erupts in a most abrupt comic-horror moment. On the other hand, the dancing can also integrate to superb effect: it works brilliantly when Susanna’s movements coordinate with those of her shadowy counterpart behind the frosted screen, or when the creepy, long-coated, dancer-versions of the two voyeuristic elders lurk behind those screens. During Joacim and Susanna’s heart-felt duet of love, painfully marred by the sorrow of being torn apart, dancers and singers interact with the utmost of tear-jerking poignancy as the couple is slowly pulled apart only to come back together over and again until finally resigned, all tumble down to gracefully enfold in tender embrace.

Lots of exciting excellence all round.

Eileen Caiger Gray