Joyce Glasser reviews Yuli – The Carlos Acosta Story (March 22, 2019), Cert. 15, 111 min.

One major problem with turning a true story into a film is that the viewer is likely to know the outcome and so building tension is problematic. This is a particular challenge with Yuli – The Carlos Acosta Story (Yuli) as the Cuban dancer is so famous, and the film is based on his revealing autobiography, No Way Home: A Cuban Dancer’s Story. But in Yuli, Spanish actress-turned-filmmaker Icíar Bollaín, and her scriptwriter husband Paul Laverty, (who also collaborated on The Olive Tree, Even the Rain and Katmandu), have turned this drawback to their advantage.

Acknowledging Carlos Acosta’s success with a choreographed framing device, the filmmakers focus on the story of the unruly young Carlos’s (newcomer Edilson Manuel Olbera Núñez) unlikely rise from poverty to fame and prosperity reminding us that the outcome was never a foregone conclusion. Within that story is the ambivalent relationship between the rebellious, headstrong, break-dancing youngest child of Pedro (Santiago Alfonso, a Cuban dancer /choreographer) and an authoritarian truck driver proud of his African roots. Unfortunately, when young Carlos transforms into a young adult as dancer Keyvin Martínez and begins to travelling the world, the film strives to cover too much ground with sketchy, lacklustre scenes.

Acknowledging Carlos Acosta’s success with a choreographed framing device, the filmmakers focus on the story of the unruly young Carlos’s (newcomer Edilson Manuel Olbera Núñez) unlikely rise from poverty to fame and prosperity reminding us that the outcome was never a foregone conclusion. Within that story is the ambivalent relationship between the rebellious, headstrong, break-dancing youngest child of Pedro (Santiago Alfonso, a Cuban dancer /choreographer) and an authoritarian truck driver proud of his African roots. Unfortunately, when young Carlos transforms into a young adult as dancer Keyvin Martínez and begins to travelling the world, the film strives to cover too much ground with sketchy, lacklustre scenes.

In the present, Acosta plays himself, the choreographer and director of a ballet that complements what we are watching in the past. We first see 44-year-old Acosta in Cuba, as he drives to the theatre for rehearsals of what will, at the end, become the ballet ‘Yuli.’ The sun is shining, the sea is blue, the streets are spotless, the famous architecture is not crumbling and all the pedestrians and cyclists are young and beautiful. This is how Acosta might see his beloved homeland, and

Icíar (as actress) and Laverty (as script-writer), who met on the set of Ken Loach’s Land and Freedom never suggest that the Communist regime narrowed Acosta’s choices or curtailed his freedom. On the contrary, we hear over and again about how lucky Carlos is to have a scholarship to such a prestigious dance school, not to mention the three square meals a day that Pedro, an impoverished father of 11, would be unable to guarantee.

But Carlos struggles against all authority and is traumatised by the thought of being labelled a ‘faggot’ by the kids in his rough neighbourhood. In his audition he impresses the staff, but states clearly, over Pedro’s objections, that he does not want to attend. While Carlos begrudgingly leaves for school at 5:30AM and is quickly made the lead dancer in a school performance, he continues to rebel.

Wandering around the city, in lieu of attending classes, Carlos stumbles across the ruins of a futuristic complex of bricks and pottery structures under spherical vaulted domes. He overhears a guided tour of what was supposed to be architect Vittoria Garatti’s new National Arts School, commissioned by Fidel Castro and Che Guevara, and reflecting the optimism of the post revolutionary period.

Work began in 1961 but with the Cuban missile crisis, the Russians had other funding priorities and in 1965, the cultural centre designed to match anything in the USA, was abandoned. This interesting scene is hardly gratuitous: older Carlos (Martínez) will return to the spot with his girlfriend and Carlos Acosta is now involved in discussions to use the site for his dance school.

When Pedro learns that his son faces expulsion due to non-attendance and a bad attitude, he is furious. He has seen his wife’s anguish as her family (white, and of European descent) make the risky journey to Venezuela and Miami and knows that his son’s only hope is the god-given talent that, somehow, Pedro recognises as exceptional. (While Carlos does not want to leave Cuba, we are made aware of the racism and double-standards as to which Cubans would be welcome in Miami.)

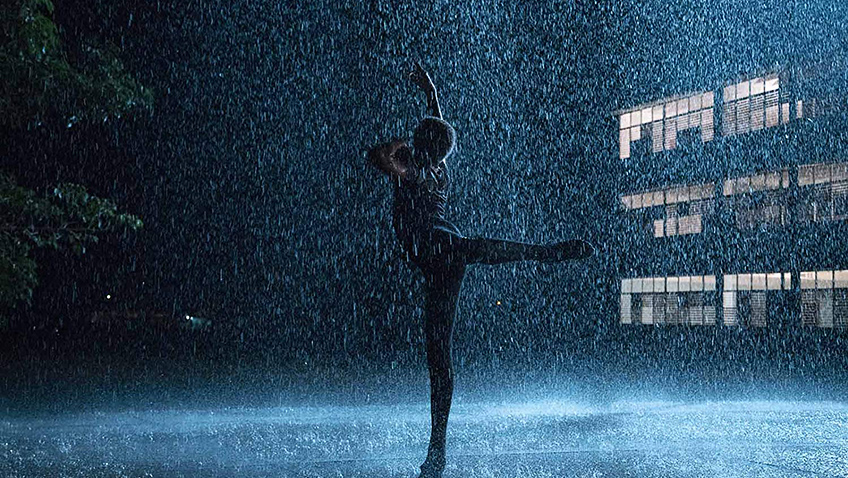

In one of the most dramatic scenes of the film, Pedro disciplines Carlos by beating him with a strap, while present day Acosta, as Pedro, is disciplining his son (dancer Mario Elias from the Acosta Danza company) on stage during a rehearsal.

Pedro pleads with the school, relying on Carlos’ devoted teacher Maestra Chery (Laura De la Uz) for help. Carlos is allowed to continue with the training on the condition that he become a boarder, which means he can only go home on weekends. Carlos’s misery is palpable. And then one day, the class is treated to a professional ballet performance where Carlos sees a strong male dancer fly across the stage and he is transfixed.

Núñez is such a vibrant, natural actor and looks so much like young Carlos that Keyvin Martinez, though a terrific dancer (with the National Ballet of Cuban and Acosta Danza) and passable actor, struggles to compete. We follow Martínez’s Acosta to a residency in Turin and other cities where, depressed from homesickness and his outsider status, he relies on repetitive, unconvincing pep talks from Maestra Chery to stay afloat. The loss of momentum and dramatic interest continue in a long segment when Acosta returns to Cuba to recuperate following a dance injury.

There is however, a cathartic moment toward the end when Pedro and his wife Maria (Yerlín Pérez) watch their son celebrated as the world’s first black Romeo and toast to him at a dinner in London. Throughout the film we have seen Pablo collecting articles about his son and pasting them into an album which is his proudest possession. You can feel Pedro’s pride that his dark skinned son from the slums of Havana has shown the world what prejudice never will.

Unlike the ‘bad boy of ballet’ Sergei Polunin (whose story, as told in the film Dancer has parallels with that of Acosta), Acosta grew out of his rebellious period and embraced his vocation, spending 17 years as a principal dancer at the Royal Ballet. Not included in the film, is Carlos’s marriage or his very recent acceptance of the job of director of the Birmingham Ballet. The White Crow, released this week, also ends long before the rebellious outsider from an impoverished back ground, Nureyev, accepts the job of artistic director of the Paris Ballet.

You can watch the film trailer here: