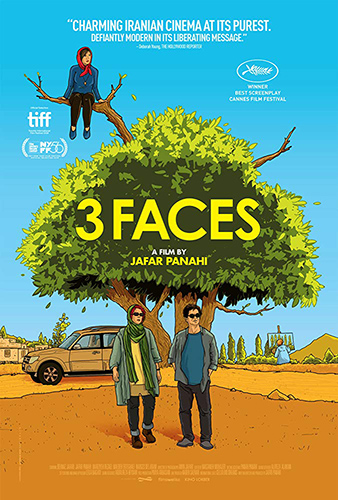

Joyce Glasser reviews 3 Faces (Se rokh) (March 29, 2019), Cert. 15, 100 min.

For most writer/directors, obstacles to getting their films off the ground and realising their vision include getting a sufficient budget, cast availability, insurance and distribution. For Jafar Panahi (The White Balloon), who along with Asghar Farhadi, is arguably the most lauded Iranian director working today, the main obstacle is political. Even before 2010, his award-winning films, The Circle and The Mirror have been banned in Iran. Since 2010, a government imposed twenty year ban on Panahi making new films, giving interviews or leaving his country is a challenge few if any directors have had to face.

This is Not a Film – smuggled out of Iran in a flash drive in a cake to open the Cannes Film Festival in 2011 – was a direct response to the threat of six-years in prison for ignoring the sentence. This was followed by Closed Curtain in 2013 and Taxi in 2015, both sweeping top prizes at the Berlin Film Festival.

This is Not a Film – smuggled out of Iran in a flash drive in a cake to open the Cannes Film Festival in 2011 – was a direct response to the threat of six-years in prison for ignoring the sentence. This was followed by Closed Curtain in 2013 and Taxi in 2015, both sweeping top prizes at the Berlin Film Festival.

In his latest film, 3 Faces, Panahi, playing a fictitious version of himself, advises a hysterical production manager whose lead actress (Behnaz Jafari) has walked off the set and has nothing else to shoot: ‘silver-lining; you’ll find a solution’. Panahi, who has become adept at subverting the ban with underground filmmaking that packs a punch, finds another solution in this multi-layered critique of Iranian society.

The film, shot in Panahi’s neo-realist style, but with a determined menacing and claustrophobic feel throughout thanks in part to Amin Jafari’s creative cinematography, begins with a home-video film within a film. Both films turn out to be cries for help.

The film-within is shot by young, aspiring actress Marziyeh Rezaei (playing a fictitious version of herself) on her mobile phone as she walks through a cave where she will hang herself. Her emotional plea, at first addressed to her best friend in her village, cites her broken dreams of going to the conservatory in Tehran and becoming an actress. Her family disapprove and want to marry her off.

In close-up shots in Panahi’s car, the actress Behnaz Jafari (playing a fictitious version of herself) is obsessing over the video, talking out loud to the phone as the message, in desperation, becomes addressed to her. ‘I’ve never seen anything from her before,’ Jafari protests in response to Marziyeh’s accusations of silence. ‘If she had my number, why didn’t she address me directly?’ Jafari asks rhetorically.

Jafari was so upset to receive Marziyeh’s video with a noose around her neck, hung from a branch (albeit suspiciously weak) in a cave, that she walked off the film set where she had been filming. Distraught, she asks her old friend Panahi to help her find Marziyeh – dead or alive.

Jafari asks Panahi to cast his professional eye on the video to see if there is a cut before the hanging, which might imply the girl was staging it (a permutation on fake news and Iranian propaganda). ‘It all looks real to me; when she falls there’s no cut,’ Panahi states. ‘Only a real pro could edit that’ he reflects, pointing out that that kind of skill is certainly not available in the villages.

Not a single word in Panahi’s artfully clever and deceptively profound script (co-written with co-producer Nader Saeivar) is wasted. Even this minor assessment of Marziyeh’s selfie-video can be taken as a critique of the brain drain in the Iranian film industry under a repressive regime. It is also a bit of a sly in-joke, as only Panahi could, perhaps, execute such a cut and it will not be a spoiler to mention that the mystery of the missing cut is never solved.

Panahi and Jafari, an attractive, strikingly pale redhead dressed in jeans, a long cotton top and a head scarf, set out on what becomes a road trip through Iran’s Azerbaijani mountain villages where Panahi is often forced to speak for both of them in his imperfect Turkish as Jafari speaks only Persian.

The quest to find and possibly save Marziyeh is, like all of Panahi’s films, seeped in metaphor and becomes a journey through patriarchal traditions about a woman’s place in society and an ignorant society’s views of art.

They meet a farmer whose bull is blocking the road after he has slipped from a cliff path. Although his legs are broken the farmer is reluctant to put him out of his misery because of his ‘golden balls.’ The farmer brags that the bull once impregnated 10 cows in one night. The bull is a hero, as well as a big earner.

A group of villagers greet the two outsiders like celebrities until they learn that they are not there to repair their electricity and water supply, but are looking for the ‘empty headed’ girl – the term applied to anyone seeking out culture or education. Then, Panahi and Jafari join those who are referred to pejoratively as ‘entertainers.’

The female villagers are more sympathetic. Marziyeh’s mother tries to help despite her fundamentalist, violent son in the house and an old lady in an open grave (which at first, they think is Marziyeh’s) is preparing for death concerned that, while she might not be evil, ‘I am not particularly good either.’

Fittingly, then, the three faces, which could be carved in Marzieyeh’s suicide cave like the presidents on Mount Rushmore, are the faces of three generations of Iranian artists. There is the aspiring Marziyeh, whose dreams are being stifled; Jafari, who works under an authoritative regime with heavy censorship and is taking a risk by being in this film; and the real-life pre-revolutionary film star, dancer and poet Shahrzaad who has been condemned to silence by the post-revolutionary regime.

Ironically, in 3 Faces, Shahrzaad’s face is never shown, but her fate is a warning to Marziyeh, as she has been the victim of arson. Her small, remote house, always bright despite the area’s electrical outages, is a refuge for women in the film and Panahi waits outside in his car like a guard. We only see Shahrzaad at a distance as she is also a painter and goes out at dawn every day to paint the countryside.

You can watch the film trailer here: