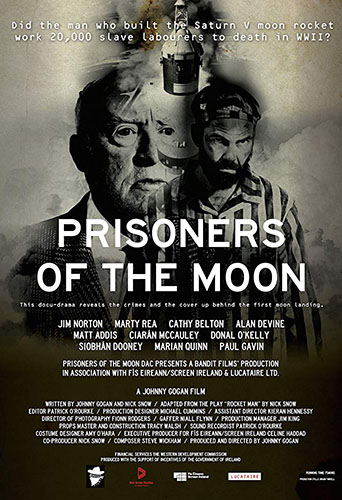

Joyce Glasser reviews Prisoners of the Moon (July 5, 2019), Cert. 15, 75 min.

Prisoners of the Moon, produced and directed by Irish filmmaker Johnny Gogan, based on the play, Rocket Man, by his co-writer, Nick Snow, has a lot going for it. An intriguing title, a fascinating subject matter, and a timely release date: the week after the release of the magnificent Apollo 11 and a week before the biographical documentary Armstrong – to coincide with the 50th anniversary of the first moon landing. Its major strength is that it aims to give us another perspective on the moon landing, one that is less wholesome, straight-forward and idealistic and patriotic.

Unfortunately, the film falls far short of its potential. Gogan seems to be so overwhelmed by his research, that he fails to present it in a coherent manner and shape it into a compelling story as in Tom Wardle’s 2018 documentary,Three Identical Strangers. Their story really has four parts, and we enter in the middle. From the outset we are deluged with information out of context and with enticing archival footage that we struggle to digest it before new names, places and interviewees are introduced, too often without captions to help us identify them. What is particularly jarring is that some of the film is told in a standard, if disorganised, documentary form with some interesting interviews, while the rest is comprised of dramatisations with Jim Norton playing Arthur Rudolph.

Unfortunately, the film falls far short of its potential. Gogan seems to be so overwhelmed by his research, that he fails to present it in a coherent manner and shape it into a compelling story as in Tom Wardle’s 2018 documentary,Three Identical Strangers. Their story really has four parts, and we enter in the middle. From the outset we are deluged with information out of context and with enticing archival footage that we struggle to digest it before new names, places and interviewees are introduced, too often without captions to help us identify them. What is particularly jarring is that some of the film is told in a standard, if disorganised, documentary form with some interesting interviews, while the rest is comprised of dramatisations with Jim Norton playing Arthur Rudolph.

So who is Arthur Rudolph? That is the question. He was, we find out in some wonderful historic detail, a space nerd who, even before the war was infatuated with space travel and revelled in movies like Fritz Lang’s Woman in the Moon (1929). In Germany in the 1930s and early 1940s he was an engineer working for the Nazi’s on the V-2 (Reprisal Weapon -2) designing and building rocket engines in Peenemünde with his mentor and then colleague, Wernher von Braun.

When the British bombed the factory complex, Rudolph was moved to the Mittelwerk facility which was part underground factory and part concentration camp. The Mittelbau-Dora concentration camp was the brainchild of SS General Hans Kammler, a sadistic engineer specialising in concentration camps. In 1944 Hitler put the V-2 project under Kammler’s control. Before Peenemünde was bombed, Rudolph, now the chief engineer (and later operations manager at Mittelwork), endorsed Kammler’s idea of using prisoners to build his (unreached) quota of 50 missiles in one month.

In March 1945, with an estimated 20,000 prisoners dead: primarily from accidents, but also from public hangings (retaliation for an attempt to sabotage the project), beatings, sickness and disease, the facility closed due to a shortage of parts.

Part two, if we are reconstructing the film, covers the period when we think Rudolph and Braun would be dragged to the Dora War Crimes Trial to face the testimony of prisoner Jean Michel (Marty Rea). Instead, they are recruited by the British, and, in March 1946, by the Americans in Operation Paperclip. The military knew that Rudolph was a card-carrying Nazi and ruthlessly ambitious, but the West was now heading into the Cold War and wanted to make use of the German talent before the Soviets did.

Thus, Rudolph and Braun begin work in the USA and become citizens. In the 1960s, they are sent to Florida to work at NASA. Rudolph, under Braun, is the assistant director of systems engineering and plays a big part in designing the systems and planning the Apollo 11 mission, giving a new meaning to ‘the dark side of the moon’.

In Part Three, Rudolph, allegedly under duress, signs a plea-bargaining agreement with the Office of Special Investigations (OSI), agreeing to leave the USA and renounce his citizenship to avoid prosecution. He owes this dramatic reversal of fortune to Eli Rosenbaum of the OSI. He had, in 1979, stumbled across a book about the role of forced labour in the construction of rocket parts. Rosenbaum did some digging in the war crimes transcripts that suggested a connection between Rudolph and the forced labour at Mittelwork.

The film begins with Part Four – in Toronto’s Pearson International Airport in 1990. Rudolph, now 83, has travelled from Hamburg to Toronto to sneak back into the USA. He tells customs officials he is there for a reunion with his daughter (who works at NASA). As Rudolph is under an OSI watch list, he is denied access to either country and returns to Hamburg where he dies in 1996.

The historic re-enactment of the immigration hearing stars Irish actor Jim Norton as Rudolph and Barbara Kulaszka (Cathy Belton) as his lawyer. The Canadian prosecution lawyer Donald McIntosh (Alan Devine) accuses Kulaszka of specialising in representing Nazis and Holocaust deniers – some of whom defended Rudolph. Despite the solid actors, the tribunal is amateur stuff and notably under-produced.

The film raises the murky question about Operation Paperclip, without answering it. Why did the US military in 1945 recruit Nazi scientists and then, nearly 40 years later, try so hard to cover it up? Appeals are refused and a congressional motion to determine whether the OSI had violated Rudolph’s rights fails to gain support

.

Although he denies it, there is strong evidence that Rudolph not only knew about the barbaric treatment of prisoners, but recommended using them to meet his quotas. Not mentioned in the documentary, Braun admitted to visiting Mittelwerk a few times and being ‘revolted’. It is Braun (and not Rudolph) who was the model for Peter Sellers’ Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb: the former Nazi who is US President Merkin Muffley’s adviser in the War Room. Braun, who worked with Disney as an adviser on proposed films about space travel, did have meetings with President Kennedy who, in 1961, delivered his famous ‘we choose to go to the moon’ speech to gather the backing of the American people.

You can watch the film trailer here: