Joyce Glasser reviews John McEnroe: In the Realm of Perfection (May 24, 2019), Cert. 12A, 95 min.

Tennis movies usually revolve around high-profile tennis matches in the USA (2017’s Battle of the Sexes), or at Wimbledon (the 2017 documentary Borg vs McEnroe, or in fiction, Richard Loncraine’s Wimbledon (2004), and Woody Allen’s Match Point (2005). Now for something a little – or a whole lot – different, French director Julien Faraut gives us a fascinating, unique and often cheeky film essay in which McEnroe shares centre stage with a host of other subjects. The stage is not in the USA or Wimbledon, but Roland-Garros. Most surprising at all, while there is the expected big match at the end (the 1984 Men’s Final match, John McEnroe vs. Ivan Lendl) we do not see much of the winner. All will be revealed.

Tennis technician, writer and filmmaker Gil de Kermadec (1922-2011) spent years analysing the technical styles of the world’s greatest tennis players. The first part of the film is devoted to him, although he is ever present (usually behind the camera in much of the 1985 footage of McEnroe that forms the basis of Faraut’s film).

One of the hallmarks of McEnroe’s style is the unpredictability of his returns, particularly backhand. ‘Lendl put the ball where his opponent was not; McEnroe put the ball where his opponent couldn’t get to.’ To merge form and content, Faraut gives us a completely unpredictable narrative, full of interesting diversions, asides, visual jokes, captions and sound distortion and effects, including the thumping on the microphone at the end of takes.

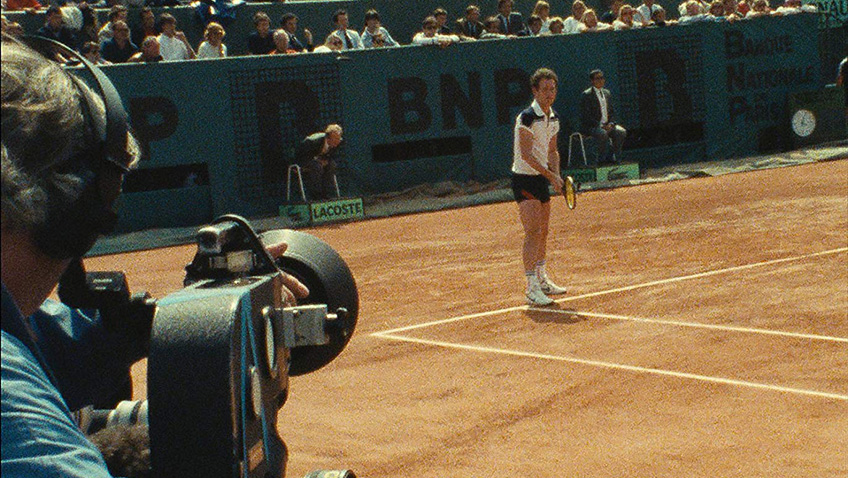

These are a reference to the noise the Arriflex 16 mm camera made shooting in de Kermadec’s preferred method: slow motion (120fps). Despite the sound blimps and equipment jackets, the sound was audible in a silent stadium. McEnroe was so annoyed with the equipment that in one shot we see him hitting the crew with his racket. De Kermadec was obsessed with finding the right position for his camera – (right behind the flower beds at that level), and in a hole in the wall – but over time, he became squeezed in –and almost out – by the news crews. The Tennis Federation’s offer to give him footage from the news crews outraged him. He was not after match coverage.

To show how Gil de Kermadec’s work led Faraut to making his rather extraordinary film, Faraut begins with the evolution of a genre of film called the Instructional Film. Before you yawn, we see how that genre has suffered from two of the same limitations as romantic comedies or war films: rigid ideas on how it should be made and produced and tight limitations on the actors. In 1966 de Kermadec, the first National Technical Director of Tennis in France, was responsible for producing training films and mounting demonstrations at the same time that he was realising how useless they were. He explains that the players in demos think they are making the same movements they do in a match. Film can demonstrate they are not.

In 1977 de Kermadec’s instructional films evolved into the technique of Portraiture, in which he analyses what makes each player unique and what type of tennis he or she can produce. After a series of studies that include Borg, Evert and Connors, the last film (1985) was John McEnroe, number 1 in the world for four years. Enter Julien Faraut who works near de Kermadec’s offices, in the audio-visual archive of France’s Institut National de Sport, Expertise et Performance and happened to find the rushes of de Kermadec’s McEnroe film. But he found 20 times the final length of the edited film de Kermadec made, and it is this footage that proved such a rich treasure trove.

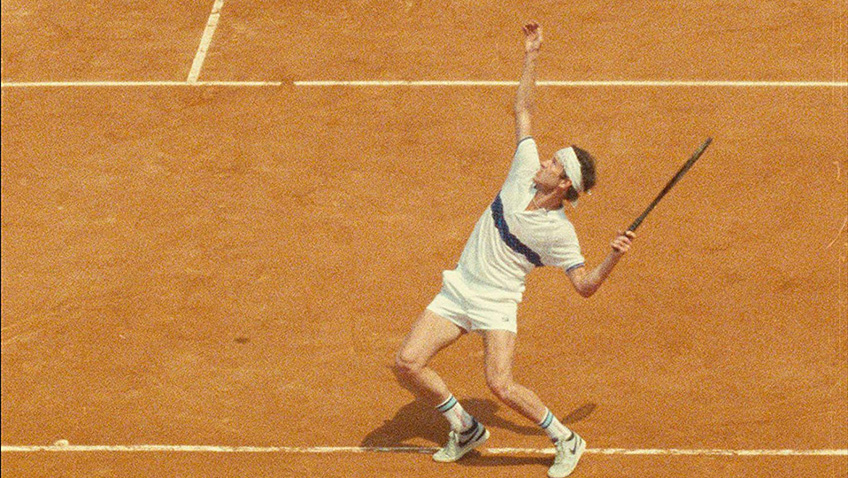

With a terrifically unexpected and eclectic score, the first shots are truly astonishing. Many of us have seen McEnroe play, but here de Kermadec focuses on McEnroe’s incredible body movement as he serves: over and again. He looks like a contortionist, a gymnast, and a ballet dancer, putting the power before the ball, and somehow keeping his balance and landing at a run forward as an athlete.

As well as McEnroe’s unpredictable backhand and tendency to rush to the net, his drop shots (which we see in action) were one of his key weapons. His technique gives him angles to play without having to volley – although he can certainly volley.

Faraut’s interest in tennis and film continues with another digression. Roland Garros is within the area called Parc des Princes, an 18th century royal hunting ground. But the ghosts that haunt de Kermadec and Faraut are those of chronophotographers Georges Demenÿ and Jules Marey, who were, like de Kermadec, obsessed with movement in sport. Marey’s studies of the physiology of birds, animals and people, prompted the English photographer Eadweard Muybridge to prove Marey’s observation that galloping horses have, at one point, four hooves off the ground.

Because de Kermadec was more interested in McEnroe’s style and technique than in the matches, Faraut had to work with a one-sided competition. We see McEnroe’s incredible footwork, serves and returns – from one side of the net. It is as if we are watching the player in competition with himself, which, as we learn, is not far from the truth with this perfectionist. We see his surgical assistant mother and his businessman/lawyer father amongst the spectators, both of whom set high standards for their sons. Players are told to worry about the things they can control. McEnroe wants to control everything: he is playing ‘a match against himself.’

Faraut comes to our aid with Dr Cédric Quignon-Fleuret. We hear his psychological theory on McEnroe’s arguments with referees and anger management issues as we see them acted out in various matches while the crowds sneer and boo. Such rage and negativity would destabilise most players, but they energise McEnroe. His tantrums of genius were so famous in the early 1980s that they inspired actor Tom Hulce’s performance in the 1984 hit film Amadeus.

After an opening quote from Jean-Luc Godard (‘Cinema lies; sport doesn’t) a second reference to Godard is a time clock (used in a similar manner in Bande à part) superimposed on the screen ticking away the 120 seconds it takes McEnroe to prepare for a serve. Speaking of time, Faraut brings in the influential French film critic Serge Daney (1944-1992) whose passion for tennis (and bull fighting) led him to write about theories of movement that drew parallels between film and those two sports.

What film and tennis have in common is the importance of time. No one can predict the length of a match and timing is crucial to a good film. McEnroe is not a filmmaker, but he writes his own scripts, drawing out time (volley) cutting it short (net/drop shot) and calling ‘cut’ with orders that the clay court be swept in the middle of the match. His plan to win the 1984 match with Ivan Lendl at Roland Garros in record time started out brilliantly, but backfired, dragging out to more than four hours and ending with a match point in the fifth round. We see the thrilling highlights – primarily from one side of the net.

You can watch the film trailer here: