Joyce Glasser reviews At Eternity’s Gate (March 29, 2019), Cert. 12A, 111 min.

After a day at Tate Britain’s magnificent exhibition, Van Gogh in Britain take a well-earned seat at NYC painter and filmmaker Julian Schnabel’s new film At Eternity’s Gate. The title is taken from a lithograph and painting that appears in the exhibition. An older man seated by a fire (suggesting the winter of life) sits on a chair with his head in his hands, his face hidden: the face of Everyman. The title is the Sorrowing Old Man but on one of seven existing prints Van Gogh inscribed the words: At Eternity’s Gate. Schnabel’s film spans the winter of Van Gogh’s short life, 1888-1890, and begins when he decides to leave Paris for Arles.

While hardly a trouble artist himself, Schnabel is drawn to making films about artists (painters or writers) who suffered and died prematurely (all under age 50) by a drug overdose (Basquiat); suicide after imprisonment and persecution in Communist Cuba (Before Night Falls); locked-in syndrome and pneumonia (The Diving Bell and the Butterfly), and, in the case of Van Gogh, a gunshot wound, arguably self-inflicted.

Although Willem Dafoe is 25 years older than Van Gogh when he died, few actors convey suffering and sorrow like Defoe. Think back to his starring role in Abel Farrara’s Pasolini, and in Martin Scorsese’s The Last Temptation of Christ.

And few artists fit the stereotypical tortured artist like Vincent Van Gogh. In his early twenties he fails in his attempt to be an art dealer (his brother Theo’s profession); a preacher (his father’s profession), and a teacher. Self-taught, he turns his missionary zeal to art, churning out some 2,000 works in ten years with only one sale. Nothing worked out for Van Gogh, who checked himself into an asylum in St-Remy de Provence before returning north, where, after 70 prolific days in Auvers-sur-L’Oise he died age 37.

Surprisingly, the age difference only becomes a problem when Van Gogh (Dafoe) plays opposite Gauguin (Oscar Isaac). Not only did Van Gogh wish to emulate the Pont Avon artist colony with which Gauguin was associated, but he could only be in awe of the man who had travelled across the globe in search of unspoilt nature, colour and light. Gauguin was 40 when Van Gogh, 35, admired his paintings from Martinique at an exhibition. Isaac, who is actually 40, is credible in the role, but it does seem odd that Van Gogh looks twenty years his senior.

Relationships were not Van Gogh’s specialty and Schnabel makes it clear that he was not an easy man to get along with. The film begins with a fictitious meeting between Gauguin and Van Gogh in which Gauguin encourages Vincent to go south in pursuit of the light. Most of the film takes place on location in Arles and in the asylum at St Remy, with a short section in Auvers. Cinematographer Benoît Delhomme creates a strong sense of place and attempts to capture Van Gogh’s unique way of seeing and style of painting with his inspired camerawork.

Perhaps because the story of Van Gogh is so well known, Schnabel dispenses with a story and provides a selection of impressionistic scenes, like brush strokes that when seen together at a distance, provide an image of a tree, or a house – or a man. This approach was carried out very literally in the impressive 2017 animated film, Loving Vincent where each 65,000 frames were hand-painted by artists, not animators in what the director called the slowest form of filmmaking ever devised. It is doubtful that Van Gogh, who painted very quickly, would have had the patience.

There is a striking scene in the asylum where a heavily tattooed old soldier (Niels Arestrup, A Prophet) entombed, next to Van Gogh in a calming bath asks his neighbour what he paints and Van Gogh answers, ‘I paint sunlight.’ In the only scene with any dramatic tension, a priest (brilliantly played by Mads Mikkelsen), who clearly thinks Van Gogh’s paintings are rubbish and frenzied, is sent to determine whether Van Gogh is well enough to leave the asylum. The priest did not bargain on encountering a madman so eloquent and conversant with the bible.

Interspersed with these episodes of a life are long passages of Van Gogh walking in Provence. (Van Gogh loved walking and would walk from Ramsgate and Brighton to London). What ruins the effect is the increasingly unbearable music by Tatiana Lisovskaya. Aiming perhaps to recreate the onset of Van Gogh’s mental illness through the music, it has the effect of driving the audience to distraction.

The script, a collaboration between 87-year-old Jean-Claude Carrière, one of the Titans of the European film industry, Schnabel and Louise Kugelberg becomes pretentious with a series of scenes whose sole function is to draw our attention to Van Gogh’s greatest hits as though the film were a slide show for Art History 101.

Van Gogh walks into the room he immortalised in The Bedroom in Arles and, ever so deliberately removes his boots, positioning them carefully – no doubt for the painting Shoes that is in the Tate exhibition. The problem is not that he painted Shoes two years before arriving in Arles, but that the emotional impact of the painting’s personification of two weary, worn out friends does not register in the scene.

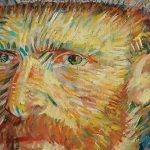

In another scene, no sooner does Gauguin beat it back to Paris, then Dafoe’s face fills the screen decked out exactly like Van Gogh in Self Portrait with Bandaged Ear. Much better, because there is some informational context to the set up, is a scene in Auvers where Van Gogh is painting Dr Gachet and we can compare the canvas to the real thing opposite. Gachet is played by Mathieu Amalric, but it is just a cameo for the actor whose brilliant performance in Schnabel’s The Diving Bell and the Butterfly contributed to its four Academy Award nominations.

Dafoe was respectfully nominated for Best Actor for At Eternity’s Gate. It’s the least the American Academy could do since Kirk Douglas won that award for the Van Gogh biopic Lust for Life and Dafoe was robbed of the Best Supporting Actor award for 2017’s The Florida Project. Dafoe delivers a tormented artist, but his character is too remote and the film is too self-conscience for us to feel much of anything.

You can watch the film trailer here: