Joyce Glasser reviews Girls Can’t Surf (August 19, 2022) Cert 12A, 108 mins.

After a terrific summer of sport in which more medals were awarded to women than men for the first time in history at the Commonwealth Games, women received the same prize money as men at Wimbledon and England’s women won the European Championships, Chris Nelius’s documentary is topical and timely. The surfers in his film (born in the 1960s and early 1970s) all had to fight the same battles as Billie Jean King, Nettie Honeyball and Jesminder “Jess” Bhamra over pay, sexist attitudes, parental prejudices and the absence of support and mentors.

Though a lot of female surfers pop up in the film, Nelius focuses on a manageable (more on that later) number, including Wendy Botha from South Africa, Jodie Cooper from Western Australia, Pam Burridge from Sydney’s Northern Beach, Pauline Menczer from Bondi Beach, and Frieda Zamba and Lisa Anderson from Florida (and California).

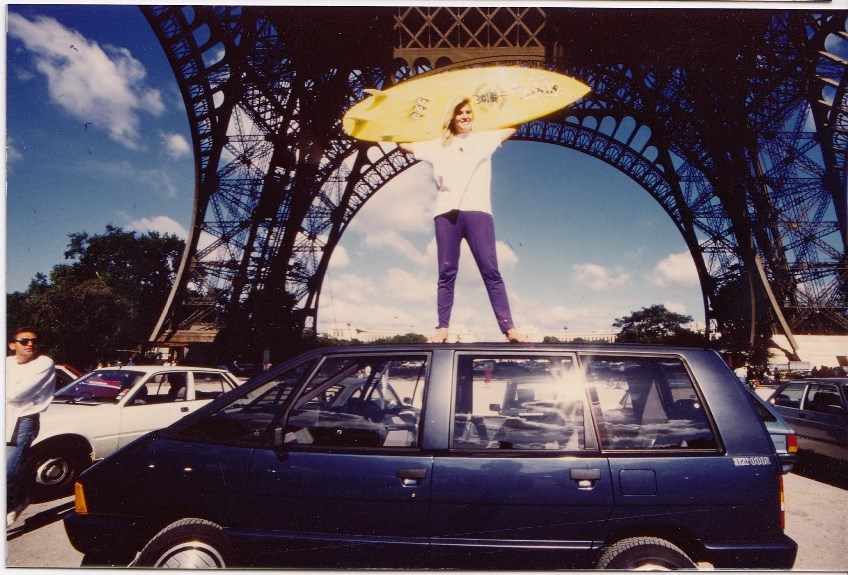

The nationalities count for little in this individualist sport where the competitors are peripatetic and some change countries and even nationalities. Many starting out without sponsorship or prize money struggle to pay their travel expenses. Lisa Anderson crossed country early on to pursue her dream. Wendy Botha won her first title as a South African citizen in 1987, then she became an Australian citizen and won three more titles.

The stunning Lisa Anderson began surfing in Florida relatively late, at 14, in the 1980s when women’s surfing was underground. When her parents disapproved of her vocation, she ran away to Huntington Beach, California where she was good enough to turn pro at 18. In the film she tells us that her father was an alcoholic and she pursued surfing because she was not as good at anything else. Anderson recalls leaving a note under her mother’s pillow, ‘I’m going to be number 1’ and kept her promise. From 1994 to 1997 she won four consecutive world titles.

Pauline Menczer had difficult personal challenges in her career, too. She grew up in Bondi Beach attached to the sea, but when she was only five her taxi-driver father, was murdered and the family struggled. In high school Pauline began suffering from rheumatoid arthritis which posed a whole new set of problems. Bad luck continued in 1991 and 1992 when Menczer came a close second to Wendy Botha but felt the top prize would always elude her.

So, it is all the more cathartic for the audience when, in 1993, Menczer, so crippled with arthritis that she could barely walk to the water, finally won the women’s world championship of professional surfers. She comments that the minute she was on her surfboard the arthritis disappeared.

Menczer had another challenge, which, like Billie Jean King, she did her best to hide. She travelled the surfing circuit with her French “coach,” who was really a girlfriend. They lived in fear of being found out. Menczer could not afford to travel with a real coach.

Many of the women in the film have, like Anderson and Menczer, overcome personal challenges before facing the general sexist challenges that united all female surfers. We hear countless examples of sexism before arriving at the Association of Surfing Professionals’ pay disparity in 1992, where a male champion would take home $1.7 million and a woman, $450,000. But many men (and we hear from one) thought that women should not compete at all.

This chauvinist view affected the surfing magazines (run by men) which had the power to bring a surfer’s career to the attention of sponsors. For surfers starting out, until the prize money comes in there is often no way to make money without sponsorship deals, so it’s a catch 22.

Wendy Botha had already achieved four championships when she decided to pose, not for a surfing magazine, but in Playboy, which gave her a higher visibility (and better pay) than an article in a surfing magazine. It was a controversial choice for her female colleagues, at a time when female surfers were still expected to appear in swimwear competitions!

It has to be said, all of the surfers in the film have bodies every bit as attractive as those of the high viz men, particularly their great legs, like dancers. This does not only come from hours on the waves, but from hours in the gym like their male counterparts.

Swimwear was also an issue for all female competitors because in the force of a strong wave, the high cut bathing costumes would “ride up” and could be painful, let alone uncomfortable. After having her first child (and still competing), Lisa Anderson played an important role in changing women’s beach fashion with the development of the women’s boardshorts. Rochelle Ballard, who set up a surf camp for aspiring young surfers, also presented boardshort lines to clothing manufacturers like Roxy and the shorts took off, becoming a fashion item as well as surfing attire.

For all its topicality and visual interest, one of the problems with Girl’s Can’t Surf is following all the stories across continents, time and age divides. The talking heads are labelled by name, but you still have to recall what each one said before and match the speaker to her younger or older self, while taking in the new content. Nelius usually begins a commentary or anecdote with the older (most of the women are now between late forties and early sixties) woman then continues it ten minutes later with that same woman, but unrecognisably younger, particularly with a dark tan, with wet hair and a wet suit or bathing costume on. When all of the featured women are juxtaposed in this manner, it becomes confusing.

Equally disappointing is the surfing footage. Nelius relies on archival footage, some of which is not of great quality and there is not a lot of it. Throughout their fight for equal rights, women surfers argued they work just as hard as men and are surfing the same monster Hawaiian waves as men but remain less visible. Girls Can’t Surf is a fun, enlightening and, in some ways, essential sports documentary, but it is not the best place to see women surfing.