Joyce Glasser reviews Oppenheimer (July 21, 2023) Cert. 15, 180 mins.

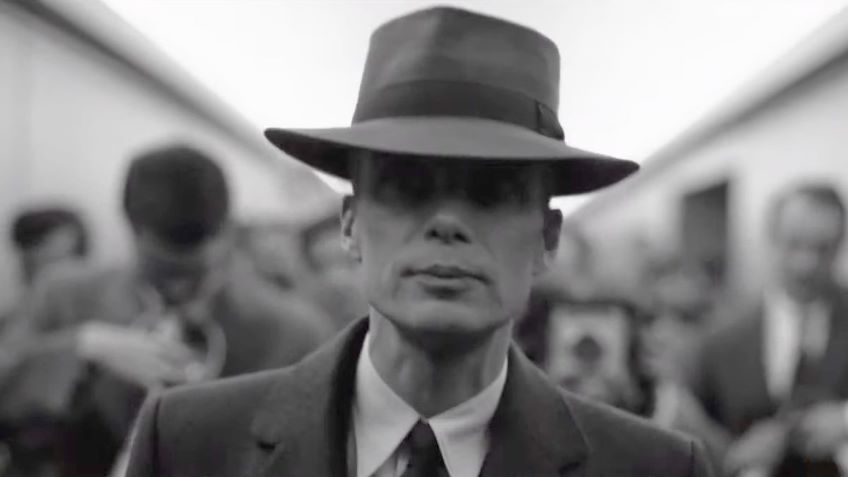

Writer-director Christopher Nolan’s new film is not another Sci-fi thriller as you might expect, but a biopic of the brilliant 20th century scientist J Robert Oppenheimer (Cillian Murphy). It is, as you would expect, shot on 70mm filmstock with Imax cameras and meant to be seen as a collective experience in dark, big screen cinemas away from mobile phones and other distractions. Please see it as intended.

Viewers of every age should know about the meritorious rise, tragic fall and quietly triumphant redemption of this complex genius and should be reminded about how scientists can be done in by politicians. Oppenheimer wasn’t the first – nor was Galileo de’ Galilei. David Kelly and Anthony Fauci won’t be the last. But for those who have not read the underlying source biography, American Prometheus: The Triumph and Tragedy of J. Robert Oppenheimer by Kai Bird and Martin J. Sherwin, Oppenheimer might be as hard to follow and frustrating as Nolan’s Tenet.

The film aims to show the arc of Oppenheimer’s triumph, culminating with his successful management of the Manhattan Project that delivered the first atomic bomb; turned him into a national hero between 1945-1947 and, just years later led to his downfall and humiliation. Oppenheimer’s hatred of Fascism and donations to Communist linked charities made him a target of Hoover’s FBI Communist witch hunt which fed into McCarthyism. The film shows that he was betrayed by three scientists with personal vendettas to settle, and perhaps real suspicions about the Soviet Union’s access to information within The Manhattan Project. But Oppenheimer made things worse by allowing himself to be baited into a fight with a kangaroo court to clear his name and retain a security clearance that was about to expire. Instead, he was disgraced and publicly stripped of it.

Nolan’s screenplay skips Oppenheimer’s life up to age 18 and begins with his education in the 1920s: Harvard University; Christ’s College, Cambridge where hopeless at experimental physics he was unhappy; and the University of Göttingen (PhD) where he thrived, excelling in theoretical physics and earning a PhD at age 23. To illustrate his frustration with Cambridge, we have the infamous incident where Oppenheimer injects poison in an apple intended for his critical professor Blackett (James D’Arcy). We are often reminded that Oppenheimer was no angel.

Boasting he was teaching something new and with papers (one leading to the identification of Black Holes) to prove it, universities in the USA fought for him. The film ends with a more contrite, but equally sincere, Oppenheimer lecturing around the world on the prevention of a global arms race in the 1950s, after John F Kennedy awards him the prestigious Enrico Fermi Award and, much to Oppenheimer’s satisfaction (and ours), rejects the appointment of the duplicitous Chair of the Atomic Energy Commission, Lewis Strauss (Robert Downey Jr, superb) to Secretary of Commerce. Shortly thereafter, Kennedy is shot but Strauss gets his comeuppance.

In-between, the film tries valiantly to squeeze in one of the busiest and most complex lives in 20th century history into three hours, and – to add to the challenge – not in a chronological fashion. Nolan has us switching amongst four or perhaps five time periods, one, a congressional hearing, mercifully marked out in black and white to help differentiate it or make it look more official, like archive footage.

Even with chronological order, confusion might linger due to the rapid editing which jumps from encounter to encounter, from country to country, from bedroom to lab room – sweeping in as many anecdotes and acquaintances as possible. Much of the film, particularly the first half, is a steady stream of handshaking and greetings as a large cast of characters, primarily scientists, are introduced to us as we struggle to make out their names. Many of the cast, including Murphy, Florence Pugh and Emily Blunt, whisper, speak in a low, throaty voice or mumble, making it difficult, even without the score, for older viewers in particular, to understand the dialogue.

There are, of course, some visually and intellectually striking, even spectacular, scenes that are easy to enjoy or appreciate. One, is particularly entertaining because the personal spark between two key characters clicks before our eyes in a witty match displaying the talents Cillian Murphy and Matt Damon. Here Damon plays soon-to-be General Leslie Richard Groves Jr. a United States Army Corps of Engineers officer put in charge of the Manhattan Project, and hence, the delivery of an atomic bomb originally intended to use on Germany. ‘Why don’t you have the Pulitzer Prize,’ Groves asks? Oppenheimer retorts, ‘Why aren’t you a General?’

It was a stroke of genius on Groves’ part to interview Oppenheimer, who had never so much as managed a Hamburger stand (Oppenheimer boastfully concedes that he could not). His brother Frank (Dylan Arnold), mistress Jean Tatlock (Florence Pugh) and wife Kitty (Emily Blunt) were former or current Communists. Generous to humanitarian causes, Oppenheimer had given money to the Spanish Civil War effort and other causes intended to fight Fascism (his parents were Prussian Jews) more than to support Communism. Groves recognises that Oppenheimer is the only candidate who is a polymath and understands not just physics, but all the issues and branches of science involved and how they would work together.

The most spectacular scene, of course, is the Trinity project itself, when, on July 16, 1945, the thousands of people who have lived in the secluded village around the Los Alamos laboratories for up to three pressured years, held their breath to see if the bomb would work. The narrative is clear, the sequence is unbroken and the tension allowed to build. Nolan stages the action as if we were there lying on our stomachs, our eyes shielded. When, just weeks after, the bomb is dropped over Japan, Oppenheimer thinks of the Bhagavad Gita, reciting, ‘I am become death, the destroyer of worlds.’ This provides the transition in his complex attitude toward the atomic bomb and his reluctance – which earns him the animosity of Edward Teller (Benny Safdie), who testifies against Oppenheimer – to develop the hydrogen bomb.

The two key women in Oppenheimer’s life are easy to spot, but neither receives much attention. Pugh plays tragic psychiatrist Jean Tatlock whose membership in the Communist Party implicates Oppenheimer. No sooner do they meet (she is 22 and a student) than both are naked in bed where Jean is turned on by her famous lover reading from the Bhagavad Gita in Sanskrit. Kitty, who leaves her third husband for Oppenheimer, was an accomplished botanist who turned to alcohol after being left to tend to their two children. But Oppenheimer’s dedication to his wife and daughter Toni (who had polio) with the life he made for them in the US Virgin Islands, which Kitty loved and Toni needed, is necessary omitted. It’s another long, complicated, tragic story, punctuated with moments of love and humanity.