Joyce Glasser reviews Claudio Parmiggiani at the Estorick Collection, London until August 31, 2025

The Estorick Collection is hosting the UK’s first retrospective of the Italian conceptual artist Claudio Parmiggiani. Not to be confused with the Mannerist master Girolamo Francesco Maria Mazzola, better known as Parmigianino, or “the little one from Parma.” The Parmigianino exhibition at the National Gallery is long over. You still have until 31 August to get lost in thought at the Estorick’s cerebral, esoteric yet compellingly entertaining exhibition. The 16th century child prodigy died at 37. Claudio Parmiggiani, born in the town of Luzzara, is now 82 and working just 50 miles away in Parma.

After reading the background note in room one of this two room exhibition, your introduction to Parmiggiani is a model sail boat made from canvas and looking the worse for wear. The ragged sails have two burnt out holes in them. Parmiggiani uses a wide variety of materials in his works, and these include fire, smoke and soot.

What to make of it? Well, the artist was 7-months old when the Allies bombed the traditional, sleepy town of Luzzara in October 1943 to disrupt German supply lines.

This 1971 sculpture of a burnt-out, wrecked sailboat, however, is not The Fighting Temeraire: the little boat is no military hero and Luzzara is 200 miles from the Tyrrhenian Sea to the west and 600 miles from the Adriatic Sea to the east.

Yet boats and their paraphernalia are dotted throughout this exhibition. The catalogue’s first image is of Shipwreck with Spectator from 2010, a monumental, damaged sailboat in the form of an Egyptian felucca, ensconced in a bay of the Church of San Marcellino in Parma, like a votive from a shipwreck on some 60,000 hardback books.

Burning, books, World War II, Egypt – the Library of Alexandria….It’s tempting but dangerous to apply simplistic labels to any artist’s work, but it’s a way in. Like all artists born during or just after WWII, Parmiggiani has to find a way to pick up the broken threads of art history and his history, shred during the horrors of this period.

Luzzara might not be on the sea, but it is on Italy’s longest, and one of its widest rivers, the Po, which empties into the Adriatic. The fishing is great, as evidenced by the wooden fragments of the hull of a small fishing boat, forlorn and utterly useless, but with an ironic lantern still lit as if to guide it to a burial by sea. Is this a memory from a childhood born into war, but created from its ruins?

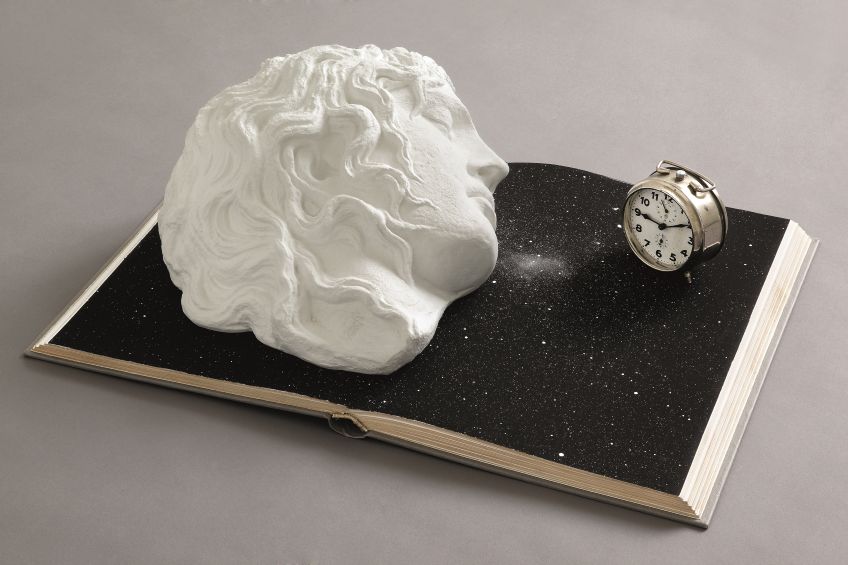

Lamps appear again in the mysteriously ironic With Extinguished Light from 1985, a plaster cast of an ancient Roman head dramatically lit on one side by an oil lamp that is so extinguished you struggle to see the glass. The source of light might be a play on Caravaggio’s chiaroscuro, but in a stand-alone sculpture, the source of light must be imagined – metaphorically or intellectually.

A bizarre sculpture from 1997 entitled What is Tradition? will catch your eye. It shows a wooden-handled vegetable knife that has stabbed the lead cast of an ear, placed on a paperback book that is itself seated on an iron plinth, the epitome of tradition. The spine of the book reads Zolla, Che cos’è la tradizione? (What is Tradition?) The polymath writer and philosopher Elèmire Zolla believed that all forms of tradition – religious, philosophical and artistic – give us a framework for understanding human existence and helps us gain access to deeper spiritual realities. In Parmiggiani’s sculpture, is Zolla’s message falling on deaf ears?

The sculpture is, at first glance, deceptive to non-Italian viewers, more familiar with Vincent Van Gogh’s infamous ear. Van Gogh, like Parmiggiani, often painted his favourite novels into his art, and Emile Zola – as opposed to Elèmire Zolla – was his favourite author. Van Gogh, too, was well versed in tradition and art history. And like Parmiggiani he was also determined to break away from it in order to pioneer expressionism, a style at first misunderstood, but soon celebrated and copied.

The great German artist Anselm Kiefer (currently on show at the Royal Academy) wrote about Vincent Van Gogh, doggedly returning to the same landscapes, attempting to capture its truth but always failing as the reality of nature defies him. ‘So,’ asks Kiefer, ‘What does he depict? Not the wheatfield, not the romantic memory of a specific summer’s day…What remains is the memory of something specific that has almost completely disappeared.

In that last sentence, Kiefer could be referring to Parmiggiani. He, too, references literature, philosophy and art history in his work and he even spent time in the workshop of one of Italy’s most famous 20th century artists, Giogio Morandi. But within a decade of Morandi’s death, Parmiggiani had broken away from the master with the Delocazioni or “displacements” that have come to define his style.

Art historian Franziska Nori points out that Parmiggiani “paints with fire. What was once there leaves blank spaces in delicate layers of soot deposited over time. Like white shadows, the empty spaces are visible traces of an absence.” Those ephemeral cabinets of vases and jars made of soot and smoke may be an homage to Morandi, but, like the ghostly book shelves opposite them that comprise the second room, they are evaporated objects, lacking the physicality that is the hallmark of Morandi’s vessels.

Arguably more important than Morandi to Parmiggiani’s ruminations on absence and memory is the great American photographer Paul Strand, who spent half of 1953 photographing the tenant farmers and towns people of Luzzara. Parmiggiani was only ten, but his artistic journey would be forever linked with the legacy of Strand’s photographs, published in his 1955 book Un Paese (A Country).

Parmiggiani’s art is, in part, a dialogue with the visual language Strand conveys in this book, primarily through his exploration of traces of the past and the effects of memory. Parmiggiani acknowledges the relationship between the two artists’ visual narratives in his own book, given the loaded title, Incipit.