Robert Altman died of Leukaemia in 2006 at the age of 81 while scouting locations for what would have been his 40th movie. To call him a workaholic would be putting it mildly. As Ron Mann’s earnest, reverential Altman reminds us, Altman anticipated his death in his ultimate film, A Prairie Home Companion. Who can forget that oddly supernatural ending when the female figure of death enters the diner taking a merry group of radio artists by surprise? ‘Death is the only ending I know,’ Altman said at the time.

A host of actors from Altman’s stable, from James Caan and Keith Carradine to Julianne Moore and the late Robin Williams, define the term ‘Altmanesque’, as ‘breaking the rules’ and ‘expect the unexpected’. It’s a pity then that Mann’s by-the-book documentary is anything but Altmanesque.

Despite being born in Kansas City, graduating from a Military Academy, serving as a fighter pilot in WWII (at age 18) and making films such as M*A*S*H, a brilliantly irreverent satire set in the Korean War (though considered an Anti-Vietnam film); Nashville and Kansas City; and the Player, a satire on Hollywood, Altman moved to Paris for a short period, complaining that he felt more appreciated in Europe than in America. His films won the Golden Bear at Berlin, the Golden Lion at Venice, and two Golden Palms at Cannes, but he had to wait until the year of his death to win an Honorary Oscar.

Altman was not one of these young film buffs who burst on the scene at age 20 with their first feature. Unable to make it as a writer after the war, he returned to Kansas City and made industrial films for the Calvin Company where he learned all aspects of making a film, from preparation to and post production. After being given a private donation to make a film, The Delinquents (purchased by United Artists), Altman began working in television. By 1969, Altman was one of the top television directors around and had even impressed Alfred Hitchcock, for whom he directed two ‘Alfred Hitchcock Presents’ programmes.

But Altman was outgrowing the medium. He was sacked for showing a shell-shocked solider; for hiring a black actor (for Kraft Suspense Theatre) and, in 1968, for including overlapping dialogue (an Altman innovation and trade mark) in a series called Countdown. Fed up, Altman left television and made his theatrical debut with the highest grossing movie of his career, M*A*S*H.

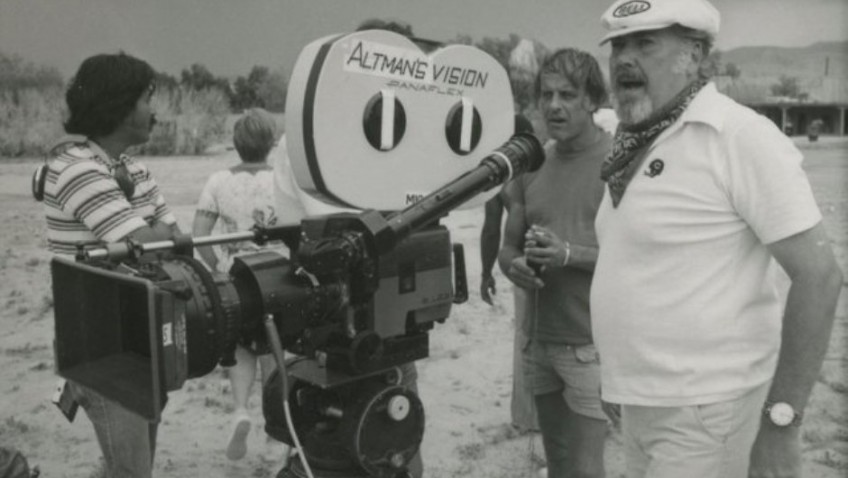

Perhaps his failure to win a Best film or Best Director Academy Award was due more to his satirical and subversive slant on American life and his personal politics than to his revolutionary and unorthodox filming methods. The documentary looks at some of Altman’s technical and stylist innovations, such as separate track sound recording which had several characters not only speaking over one another, as one does in real life, but being recorded with equal strength, so that the audience did not know who to listen to. His constantly moving camera contributed to his unique naturalistic style.

His departures from the script (angering a lot of writers) and preference improvisation, ensemble casts, and wonderful use of music (think of what McCabe and Mrs Miller did for Leonard Cohen and vice versa), are just a few of the qualities that made that film, and others like M*A*S*H, Thieves Like Us, The Long Goodbye, Short Cuts, Nashville and The Player so fresh and unique.

Mann’s decision to make a comprehensive, chronological documentary of 95 minutes, naturally results in a superficial look at a lot, including what made Altman such a maverick. Altman’s widow, his third wife Kathryn Reed with whom he was married for 47 years, is the only recurrent talking head, and you could suspect that her involvement in the film was as much an advantage as a drawback. The only ‘dirt’ slung at this fiercely headstrong auteur is from his son Stephen who claimed he was not around a lot. The fact that his son Michael wrote the lyrics for the theme song to M*A*S*H, Suicide is Painless, when he was 14, might suggest a more troubled childhood.

The result is that those who know little about Altman will emerge much better informed, but those who admire the Director for his technical innovations and irreverence will learn less, while finding little to admire in this standard bio doc.

Joyce Glasser – MT film reviewer