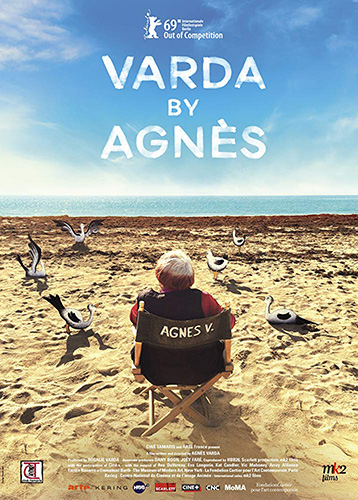

Joyce Glasser reviews Varda by Agnès (Varda par Agnès) (July 19, 2019), Cert. 15, 114 min.

The French photographer, installation artist and one of the only female filmmakers linked to the nouvelle vague, Agnès Varda, died on 29 March shortly after completing her final film, Varda by Agnès. As the title suggests, this is a unique retrospective, curated by the writer/director herself who gives an illustrated talk on her life’s work as though putting her house in order at age 90. There is not a cynical or pretentious bone in her body, and she speaks with humour and candidness about the flops (the star studded 1995 One Hundred and One Nights) as well as the successes (Vagabond). Varda’s empathy and humanistic values come across as, seated in a huge theatre before a live audience, she provides, in her lucid manner, insights into her work and the person she is.

What you will notice, however, is how auto-biographical her films are, and not just Jacquot de Nantes, her tribute to her husband Jacques Demy who is too weak in 1990 (he died 27 October that year) to turn notes and recollections of his life into a film. ‘I wanted to be as close as possible to him’ she points out, as a way of explaining why she merged documentary (scenes of Jacques dying) with drama (a recreation of his life with actors playing him as a boy and young man).

What you will notice, however, is how auto-biographical her films are, and not just Jacquot de Nantes, her tribute to her husband Jacques Demy who is too weak in 1990 (he died 27 October that year) to turn notes and recollections of his life into a film. ‘I wanted to be as close as possible to him’ she points out, as a way of explaining why she merged documentary (scenes of Jacques dying) with drama (a recreation of his life with actors playing him as a boy and young man).

Varda objects to the term masterclass, but film students have paid a lot of money to learn a lot less. “… I need to tell you what led me to do this work for so many years. Three words are important to me: Inspiration, creation, sharing. INSPIRATION is why you make a film. The motivations, ideas, circumstances and happenstance that spark a desire and you set to work to make a film. CREATION is how you make the film…Creation is a job. The third word is SHARING…You make films to show them…People are at the heart of my work.’

Varda begins applying these three words to her films in chronological order and then abandons that idea for a more random approach, linking them with clever transitions. That said, even those familiar with Varda’s main body of work might be confused at times at what we are watching and where we are in time and place. She includes excerpts from her lesser known works, and often you can see why they remain so.

Varda’s first feature, La Pointe Courte (1955), already shows signs of her idiosyncratic style. For Varda, ‘style’ when applied to film, is ciné-écriture (film writing: the sum total of all the decisions a director makes. A Parisian couple, Silvia Montford, and Philippe Noiret, visit the man’s home town of La Pointe Courte, an insular fishing village, when their four-year marriage is in trouble. Varda contrasts a dramatic style, existential dialogue and experimental foreground sound when shooting the couple, with the documentary style of the background village, telling us how she achieved a neo-realist effect before having seen any of those films.

Arguably her signature feature, Cléo de 5 à 7, is famous for having been shot in (near) real time. The inspiration was the collective fear of cancer (and Varda’s), the hand of fate and the notion of the objective vs. the subjective notion of time, something relevant to the beautiful heroine, a singer, anxiously waiting for the news of a test for cancer. Talking about the ‘creation’, she explains how the tight budget determined the location, Paris. The ‘Sharing’ element is the angst of a young, attractive woman facing death and the country’s preoccupation with the Algerian War, another kind of death sentence that preoccupies a soldier whom the heroine meets while obsessed with her own mortality.

The 1976 Daguerreotypes, was also shot in Paris, on the filmmakers’ street. It is a fly-on-the-wall collective portrait of the people that occupy the shops of the Rue Daguerre, Paris. ‘The merchants are not very open or nice to outsiders; …‘They represent the silent majority,’ Varda tells us. ‘But nothing is banal if you it them with empathy and love.’

In one of her clever transitions, she adds. In contrast to what I just said, it occurred to me that I once filmed an enraged minority. She then supplies the inspiration, creation and sharing angles on her short film The Black Panthers, shot in Oakland in the summer of 1968. Her interview with Kathleen Cleaver, newly married to Eldridge, about the power of women in the BP Movement led to Varda’s short film, Women Reply. A declared feminist, Varda dealt with the topical issues of contraception and abortion rights in her 1977 feature, One Sings, the Other Doesn’t.

Varda made another story of a girl enraged, but one who acts alone. In discussing what is arguably her most famous and award winning film, Ni Toit Ni Loi (Vagabond, 1985), Sandrine Bonnaire (now 51) joins the director on a camera dolly in the middle of a field where the director has been explaining the significance of the tracking shots in the film. Bonnaire is only half joking as she reveals a more ruthless, driven side to the director in recollecting the hardship, (and in the body-bag scene, the trauma) the 17-year-old endured in preparing for the role and in filming it.

Varda divides her life by the centuries, primarily because of the arrival of the digital camera. Nowhere is the power of this tool, and her background as a photographer, more evident than in the wonderful documentary Faces Places, made when Varda was 88, and nominated for an Academy Award last year.

The last portion of this revealing film gives us a glimpse of Varda’s eye-opening installation art, and you can only wish the Pompidou Centre would mount a retrospective to accompany this release. Varda might have begun her career as a photographer, and ended it as an installation artist, but her films are dotted with lines you can dwell over: ‘If you opened people up, you will find landscapes, if you opened me up, you would find beaches.” This is not a throwaway line, either. Many of her films do take place on or around beaches and ‘The Beaches of Agnes’ is just one of them.

You can watch the film trailer here: