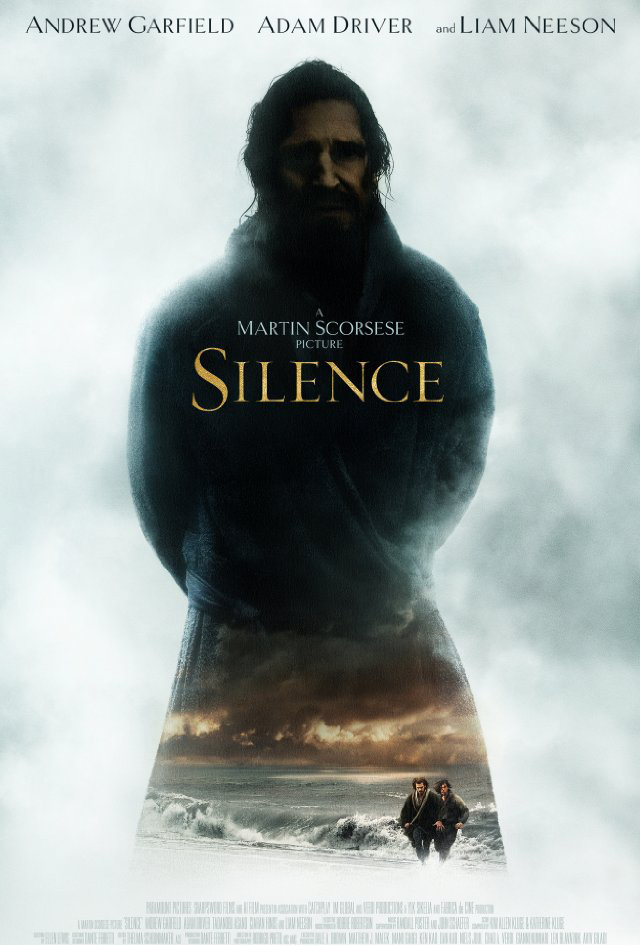

Joyce Glasser reviews Silence (January 1, 2017)

There is plenty of speaking and sound in Silence, Martin Scorsese’s faithful adaptation of Shūsaku Endō historical, epic novel (based on true events) about Christian faith. The sound ranges from the waves rolling into the shores of Japanese islands where a minority of converted Japanese-Christians hide from the Buddhist regime, to the groaning of the Kakure Kirishitan (“Hidden Christians”), being tortured by the powerful Inquisitor, Inoue (Issey Ogata). There is almost no music. The silence of the title is the silence which meets Portuguese Jesuit Missionary Sebastião Rodrigues (played by Andrew Garfield) when, in his anguish, he calls on God for answers.

There is a tower of Oscars and Oscar nominations between Director Scorsese, 74, (The Departed); his editor of the past 40 years, 76-year-old Thelma Schoonmaker (whose three Academy Awards are for Scorsese’s films); and his gifted cinematographer, 51-year-old Rodrigo Prieto (Brokeback Mountain). Silence is a labour-of-love (presumably everyone accepted union scale pay to keep the enormous budget down) that the Catholic director has wanted to make for the past twenty years. And yet Scorsese’s last film (another collaboration with Schoonmaker and Prieto), was The Wolf of Wall Street, a film so devoid of a spiritual dimension that is almost as if Silence were an act of redemption.

There is a tower of Oscars and Oscar nominations between Director Scorsese, 74, (The Departed); his editor of the past 40 years, 76-year-old Thelma Schoonmaker (whose three Academy Awards are for Scorsese’s films); and his gifted cinematographer, 51-year-old Rodrigo Prieto (Brokeback Mountain). Silence is a labour-of-love (presumably everyone accepted union scale pay to keep the enormous budget down) that the Catholic director has wanted to make for the past twenty years. And yet Scorsese’s last film (another collaboration with Schoonmaker and Prieto), was The Wolf of Wall Street, a film so devoid of a spiritual dimension that is almost as if Silence were an act of redemption.

If Silence touches a personal chord for Scorsese, a man who might be battling with unanswered questions, for most viewers it is a technically brilliant and uncompromising cinematic achievement. Scorsese throws away the director’s rule book, with its establishing shots, and tries to immerse his audience in Japan 1639, following the defeat of the Catholic peasants’ Shimabara Rebellion in the Edo dynasty. An added obstacle – most of the narrative is epistolary, passages taken from the letters written from missionary Sebastião Rodrigues (based on Giuseppe Chiara) back to his leader, Father Valignano (Ciarán Hinds) in Portugal.

You might marvel at the technical achievements throughout this overly long, two-hour and forty minute film, while longing for some emotional connection to the brutal, repetitive story and the frustrating human dimension.

The novel and film are structured, like Heart of Darkness and the film inspired by it, Apocalypse Now, as a search for a missing leader who might be dead or insane (or, the equivalent, here, espoused Buddhism and gone native). Two eager young Jesuit missionaries, Rodrigues and Francisco Garrpe (Adam Driver) persuade Father Valignano to allow them to search for their missing mentor, Cristóvão Ferreira (Liam Neeson), refusing to believe he could have committed apostasy.

Valignano is reluctant to let them go due to the high risk of death and the odds against finding Ferreira. While the priests hope to provide spiritual continuity to the remaining Kakure Kirishitan in Father Ferreira’s absence, something in Rodriques, in particular, is searching for the glory that might come from martyrdom.

The hardships Father Valignano warned them of are nothing compared to the reality that greets the two missionaries. Their compensation is the sacrifices made by the humbling faithful, although Rodriques is also concerned that they value the outward symbols – the crosses and amulets – more than the inner spiritual faith.

Some limited relief is provided by Kichijiro (brilliantly played by Yōsuke Kubozuka), a handsome wild-man, who is either a simpleton or cleverly deceptive. Kichijiro is a Christian who, after seeing his family slaughtered, continually apostatises to save his skin, and even betrays Rodriques, like a Judas character. In one of the most poignant scenes in the film, one touched with a nice irony, Kichijiro is given away by an oversight that might resolve the question of his allegiances.

Following the rebellion (we see the consequences in a gory prologue), the Tokugawa Shogunate has closed its borders and tightened security, while enforcement officials have devised a new way to ferret out the Christian peasants. They ask them to step on a fumie, a primitively carved image of Christ, or spit on it. Those who refuse are hung upside down over a pit and slowly bled. The Inquisitor does not want any martyrs, so he has devised a special test for Rodriques (who is, half way through the film, separated from Garrpe and eventually captured). Rodriques is fed three meals a day but made to watch and listen to his flock dying, even if they apostatise. What Inoue wants is for Rodriques to apostatise. The last quarter of the film is a kind of ‘will he or won’t he,’ while innocent people die.

Rodriques, who has emerged as a rather arrogant man despite the sin of pride, starts to doubt everything in his life when he rediscovers Father Ferreira, and the silence is broken in a way that is more human than spiritual. The mist and foliage that has obscured much in the film, turns to clarity in the final quarter.

Our own journey as viewers of this spectacle might not be one that Scorsese envisioned. Perhaps with the cast originally considered – which included Gael García Bernal and Benicio del Toro – the English language might not have seemed so jarring in a film that strives for authenticity in so many period details. Some viewers might find parts of the film boring, but the real problem is the absence of that spiritual uplift that Rodriques is searching for.

You can watch the film trailer here: