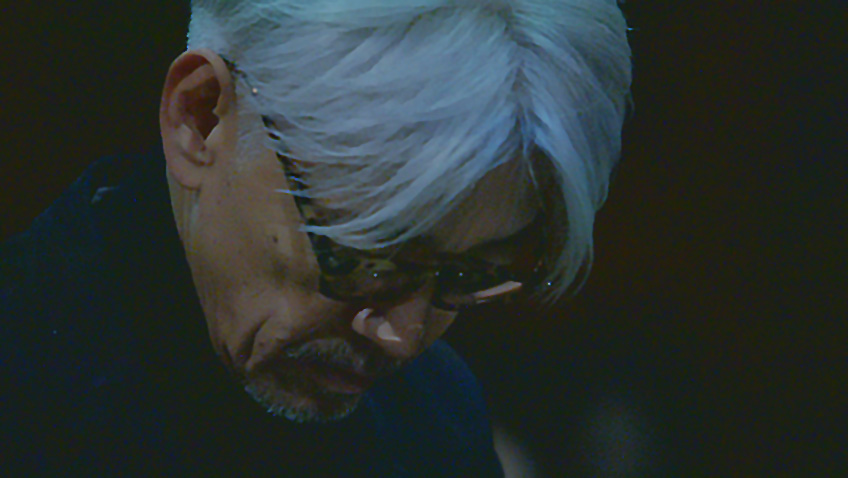

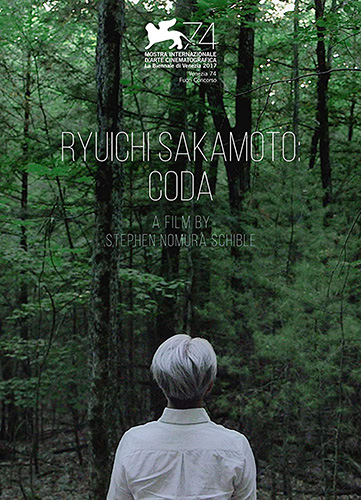

Joyce Glasser reviews Ryuichi Sakamoto: Coda (June 29, 2018) Cert. PG, 101 min.

Academy Award, Bafta, Grammy, Golden Globe winning musician and composer Ryuichi Sakamoto, 66, is to contemporary music what fellow-Japanese architect Sou Fujimoto (now with an exhibition at Japan House in London) is to contemporary architecture. While their work is high-tech, it is steeped in tradition and profoundly influenced by nature. Fujimoto says about his architecture, ‘I really like the idea of being in a forest,’ and we see Sakamoto wander through a forest gathering sounds and reflecting on nature and technology as he plays a ‘tsunami piano.’ Japanese-born director Stephen Nomura Schible’s portrait of the artist coming to terms with throat cancer is informative, enlightening and notable for what it omits.

One of the joys of spending time with Sakamoto is benefitting from his associative mind and sharing the things that delight him – a man who has travelled the globe and has an impressive address book. But before that, we watch Sakamoto campaigning against something that does not delight him: nuclear power.

One of the joys of spending time with Sakamoto is benefitting from his associative mind and sharing the things that delight him – a man who has travelled the globe and has an impressive address book. But before that, we watch Sakamoto campaigning against something that does not delight him: nuclear power.

When the film opens Sakamoto is touring contamination zone and speaking in Futaba Town Hall. Futaba has a population of zero following the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster of 2011 and Sakamoto joins a student protest – the first since the ‘restart’. ‘If I feel strongly about something,’ Sakamoto tells Schible, ‘I have to speak my mind.’ But sometimes music is as powerful as words. When Sakamoto plays the piano at a high school in the former evacuation zone, it is a powerful experience. His music can elicit tears as he plays an excerpt from his score for Nagisa Oshima’s film Merry Christmas Mr. Lawrence, accompanied by a young cellist and violinist.

Another thing the committed environmentalist, social activist, former actor, dancer, and musician does not like, is, obviously living with throat cancer. He has taken a year off to focus on getting well and we see him taking a series of pills and then nibbling at pieces of fruit cup up into small sizes. His mouth is not producing saliva and ‘I feel that I have 70% swallowing capacity’ he tells us candidly.

Despite declaring a hiatus, when Alejandro G. Iñárritu asked him to score his new film, The Revenant (2015) he could not resist ‘the opportunity to work with such a talented artist.’ Sakamoto was responsible for the score of the Academy Award nominated film, along with Alva Noto, a 52-year-old electronica and glitch music virtuoso whom Sakamoto does not mention. Reflecting on his decision to take on this job, he muses, ‘I don’t know how long I have left: 20 years, 10 or a relapse reduces it to one. But I want to make music I won’t be ashamed to leave behind.’

So far, he has nothing to worry about in that department. He takes us back to Merry Christmas Mr. Lawrence. Oshima wanted Sakamoto in the film as an actor, but, already successful from his Yellow Magic Orchestra band since 1978, and a first solo album (A Thousand Knives) that fused electronic with traditional Japanese music, Sakamoto bargained. He would be in the film if he could compose it. The 1983 film features intense scenes between Sakamoto’s Japanese Captain and a prisoner of war (David Bowie). The young Sakamoto looks as androgynous as Bowie.

His relationship with Italian director Bernardo Bertolucci (and British producer Jeremy Thomas) is also one of mutual respect and admiration. Sakamoto has composed the scores for three of the Bertolucci’s films: Little Buddha, The Last Emperor and The Sheltering Sky and he comments on the last two. We hear a passage that is read by Paul Bowles from his source novel that has particular relevance for Sakamoto with his cancer diagnosis: Because we don’t know when we will die, we get to think of life as an inexhaustible well. Yet everything happens only a certain number of times, and a very small number really …How many more times will you watch the full moon rise? Perhaps twenty. And yet it all seems limitless.

If Sakamoto feels compelled to protest, he has a great capacity to enjoy life and its influences. We watch him potter around his recording studio in the basement of his elegant NYC Brownstone (from where he witnessed 9/11) experimenting with sound. He was profoundly moved by Andrei Tarkovsky’s 1972 film Solaris and has been striving every since to make soundtracks like Tarkovsky’s. ‘I just can’t copy how Tarkosvky interprets Bach,’ he says, matter of factly: I have to write my own chorale.’ Fascinated with Tarkovsky’s use of water, wind and rain, he goes off literally ‘fishing for sound’ in the melting snow of the Arctic in 2008.

While Sakamoto is an environmentalist, he flies around the world for a living and depends on high powered electrical devices for his music. Schible asks Sakamoto how he uses computers. He keeps it simple. ‘It plays fast difficult passages for you that the human fingers cannot keep up with. The computer lets you make music even if you can’t play the piano.

But Sakamoto certainly can play the piano; the instrument he returns to for composition. Back in the evacuation zone, Sakamoto finds a badly damaged, waterlogged piano in the tsunami wreckage. This leads him to reflect on the evolution of the piano, an instrument made of wood. ‘The piano,’ he says, ‘is nature forced into shape. But pianos need retuning. It’s nature’s way of reverting to its natural state.’ The tsunami was a force on the piano and two asynchronous notes it produced formed the basis of the theme for The Revenant, a film about a damaged man in his own kind of hell dealing with the ravages of nature.

It must have occurred to Sakamoto that his tsunami piano is the equivalent of Chopin’s Juan Bauza piano, a flawed, non-professional instrument that Chopin was forced to use when his Pleyel piano was held up in customs. Frustrated with the primitiveness of the Bauza piano, he was, as is Sakamoto, making the instrument’s limitations part of the DNA of his music.

Some viewers might themselves frustrated at the complete absence of any mention of Sakamoto’s friends, wives and children, and you might want more film anecdotes. But in many other ways, this is an intimate and satisfying profile of a musician ever-striving to purify sound.

You can watch the film trailer here: