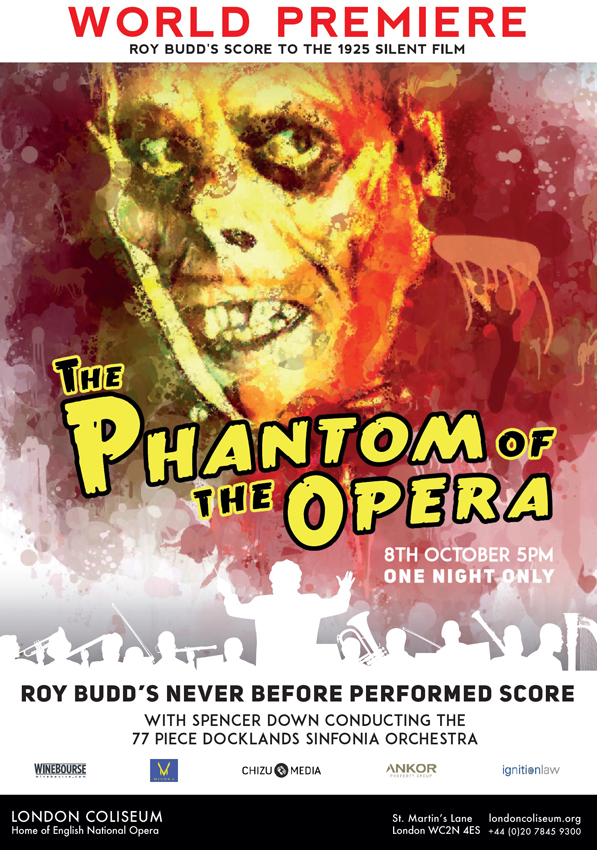

Joyce Glasser reviews The World Premiere of Roy Budd’s Phantom of the Opera (8 October 2017) Cert PG, 93 minutes (with a 20 minute interval)

The spirit of the late composer Roy Budd was present in the London Coliseum on Sunday night as the premiere originally set for September 1993 finally took place to a full house and a standing ovation.

In 1989 Budd purchased the only surviving print of Rupert Julian’s 1925 silent horror film, The Phantom of the Opera, starring Lon Chaney and set about restoring it. He also spent three years composing the romantic, anguished score which fans of Budd’s jazz compositions would hardly recognize were it not for its quality. The 77-piece Dockland’s Sinfonia under conductor Spencer Down let every note and instrument speak without dominating the film. Music and image were in perfect harmony – as Budd intended.

In 1989 Budd purchased the only surviving print of Rupert Julian’s 1925 silent horror film, The Phantom of the Opera, starring Lon Chaney and set about restoring it. He also spent three years composing the romantic, anguished score which fans of Budd’s jazz compositions would hardly recognize were it not for its quality. The 77-piece Dockland’s Sinfonia under conductor Spencer Down let every note and instrument speak without dominating the film. Music and image were in perfect harmony – as Budd intended.

It was a joyous occasion, but with a sense of sadness, as Budd died suddenly on 7 August 1993, five weeks before the premiere was to take place. That event was immediately cancelled. Budd’s widow, Sylvia, introduced the evening. It was the culmination of a 24-year campaign to make her husband’s music heard. She transferred the music to CD; synced it with the film, which you can purchase as a DVD and continued to push for a live premiere.

This time the Premiere was not scheduled for the Barbican Centre but, more fittingly, at the London Coliseum where Budd had made his piano debut at age six in 1953.

Budd, previously known for his ‘talking’ film scores, including Get Carter and The Wild Geese will now be remembered, too, for his silent film score – and what a score! There are some passages that might remind you of Andrew Lloyd Webber’s musical version, but Julian’s film is very different from the stage musical.

Budd took the decision to write the music from the point of view of the Phantom (Chaney), as opposed to Christine’s (Mary Philbin). In this way, when the Phantom is spooking the new Opera House owners and threatening Christine’s rival, Carlotta (Virginia Pearson), we hear a subtly comic harpsichord. Budd puts us inside the Paris Opera, too, by seamlessly incorporating bits of Gounod’s Faust (the opera being performed by the Paris Opera in the film) into his own score.

In Rupert Julian’s film the Phantom (who says that his name is Erik), is an opera loving convict who was imprisoned in the former torture chambers and dungeons under the Opera House after the second Revolution. We do not have much opportunity to see or hear Christine profiting from her initial agreement to follow Erik down to his underground lair. This claustrophobic hideaway is portrayed as a kind of hell separated from the land of the living by the Black Lake – a symbolic River Styx or Lethe.

Today a hint of romance between the tragic Phantom and the singer would not go amiss as it would enrich the plot and the tension. In the 1925 version, Christine gets her chance to shine, not by improving under the Phantom’s tutelage, but because he destroys her competition. Budd’s score creates some empathy for the otherwise one-dimensional Erik. For example, when he first sees Christine in his subterranean world he the score evokes the smitten creature’s overwhelming surge emotion and not the Christine’s fear as she realizes she has been kidnapped by her stalker.

Today a hint of romance between the tragic Phantom and the singer would not go amiss as it would enrich the plot and the tension. In the 1925 version, Christine gets her chance to shine, not by improving under the Phantom’s tutelage, but because he destroys her competition. Budd’s score creates some empathy for the otherwise one-dimensional Erik. For example, when he first sees Christine in his subterranean world he the score evokes the smitten creature’s overwhelming surge emotion and not the Christine’s fear as she realizes she has been kidnapped by her stalker.

Julian exhibits a kind of visual poetry in marrying the movement of the characters with the architecture of the Paris Opera House. In one scene, the ballerinas run down a spiral staircase like the angelic musicians in Pre-Raphaelite artist Edward Burne-Jones’s 1880 painting, The Golden Stairs. Budd matches this with his score in passages that are like musical onomatopoeia. Instruments that have blended and soared together become distinctive sounds with connotations of their own; as they do in Russian composer Modest Mussorgsky’s 1974 masterpiece, Pictures at an Exhibition.

The print’s restoration shows off the vivid colour that is most notable when Erik shows up at the annual masquerade ball dressed as Edgar Allan Poe’s Red Death. The action sequences are visually stunning and more suspenseful than many an action/thriller released this year. When Christine’s lover – the dashing Vicomte Raoul de Chagny (Norman Kerry) — and the super-cool, undercover Police Inspector Ledoux (Arthur Edmund Carewe) almost expire in the heat of Erik’s Hades, they are so convincing you might find yourself shedding a layer.

The acting is excellent across the board, but of course, the star is Lon Chaney Sr. (who also starred in The Hunchback of Notre Dame) who makes his feelings known through his masks and Jim Carrey-like body movement.

Chaney was only a year older than Budd when he, too, died prematurely – of throat cancer in 1930. Chaney excelled at playing grotesque, but heart-rending characters: a result of his empathy for these outcasts and his talent with make-up. Make-up departments were almost non-existent in 1920s film production and Chaney gained a competitive advantage showing up for auditions in character with remarkably deformed heads and faces. For this film he went back to the description in Gaston Leroux’s 1910 novel for what is probably the most accurate of all the depictions of the eponymous character.

You can watch the film trailer here: