Joyce Glasser reviews Pissarro: Father of Impressionism (in select cinemas for limited time only from May 24, 2022) Cert. U, 94 minutes. You can find a screening near you by following this link.

The Exhibition on Screen series travels to the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford, England and the Kunstmuseum in Basel, Switzerland, where Camille Pissarro’s life and art are celebrated in a fortuitous collaboration.

The Basel exhibition is over, but you can still see Pissarro: Father of Impressionism in Oxford until 12 June and you won’t want to miss it. This is not a retrospective: the formative paintings from the young painter’s time in Caracas, Venezuela; the London paintings during the 1870-71 Commune and a 1890 visit, and his first “commercial paintings”, the late city scapes of Rouen and Paris, are absent or in short supply.

But we reap the rewards of the Ashmolean’s best kept secret. In 1952, eldest son Lucien Pissarro’s English widow, with whom Lucien ran the Eragny Press in England, gifted the Pissarro archive to the Ashmolean. And that is what makes this exhibition special. The archive contains several paintings, 800 letters, and art by the whole family, including a fascinating 1900 drawing by Georges Pissarro. Entitled The Impressionist Picnic, the humorous drawing shows Armand Guillaumin, Pissarro and Gauguin enjoying Madame Pissarro’s cooking, while Cézanne works on a landscape. The archive contains hundreds of Pissarro’s pastels, drawings, drypoint and aquatints, etchings and engravings, including a brilliant portrait of Cézanne.

For Pissarro was, according to Claire Durand-Ruel, whose famous ancestor was Pissarro’s lifelong supporter and dealer, the most versatile of all the impressionists. Versatile not only in his use of all mediums, but in his changing oil painting style. He began with the Barbizon School style; lightened his touch and palette with rural impressionism and dabbled in post impressionism – even pointillism (View from my Window Eragny,1886) – before returning to heightened impressionism in the last decade of his life, about 1893-1903. Due to an eye abscess, he was forced to paint indoors for the first time and his hotel views of the bustling cities of Rouen and Paris sold so well that he could provide for his family after his death.

While the focus of the exhibition is this rich, family archive, the exhibition, and David Bickerstaff’s film (co-written with Producer Phil Grabsky), give us an intimate portrait of this driven artist. We see him as a great friend; a family man who, much to his long-suffering wife, Julie’s chagrin, encouraged all his children to pursue a life in art; a painting companion to Monet, Cézanne, Gauguin and even Van Gogh; a networker, an anarchist, a restless experimenter and an innovator.

Banish the thought of the reclusive, self-obsessed, anguished artist. According to the seven eloquent and persuasive experts who appear on screen, Pissarro was charismatic; open hearted and open minded, and, in the opinion of the Ashmolean’s Colin Harrison, “devoted to his family, accommodating, very curious, and completely upright – the byword for honesty and probity.” The famous author and art critic Emile Zola, wrote in 1868, that ‘a beautiful picture by this artist is the act of an honest man. I can give no better definition of his talent.’

But what about the claim to being the Father of Impressionism? It is not only that, with his long patriarchal beard he looked the part. Camille Pissarro was the driving force of the Impressionist movement and responsible for its longevity. Paul Cézanne wrote: “We learned everything we do from Pissarro. It’s he who was really the first impressionist.”

For although it was a critic’s snide remark about Monet’s painting, Impression, Sunrise that gave the movement its name, it was Pissarro who, fed up with the hierarchical, bourgeois salon system where his work languished unnoticed, spearheaded the formation of a registered company of Independent Artists (that included Mademoiselle Berthe Morisot). The first of eight “Impressionist Exhibitions” from 1874 to 1886 was held at the photographer Nadar’s art nouveau studio, 9 Blvd des Capucines. Pissarro was the only artist to show in all eight.

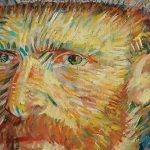

His impressionism, however, was never geared to bourgeois tastes or dealers’ needs. Instead of focusing on the activities of the bourgeoisie (ballet, opera, racetrack, cafes, pretty gardens) and the industrialisation of Paris (bridges, railroad stations, smokestacks) as did Manet, Sisley, Monet, Renoir and the post impressionists such as Seurat and Signac, Pissarro painted the working class in the countryside (Père Melon Sawing Wood, 1879) and the marketplaces (The Pork Butcher, 1883). He was not a great portraitist like Cezanne and Renoir, although there are some moving family and self-portraits in the exhibition. The majority of people in his paintings are women, but he is not showing their femininity, or women involved in domestic and parental tasks. Pissarro’s women are hard at work outside.

Pissarro was born on 10 July 1830 in Charlotte Amalie on the island of St Thomas in the (then) Dutch West Indies to Jewish parents of Sephardic ancestry, although Camille did not have a religious upbringing. His father moved there to take over an uncle’s hardware business and then caused a stir by marrying his uncle’s widow. Forty one years later, Camille defied his parents by marrying (during their two years in London to escape the Franco-Prussian war) his parents’ former servant, a French Catholic peasant (painting, Julie Pissarro Sewing, The Red House, Pontoise, 1877).

Camille knew what he needed. Julie’s ability to run the household on very little money, put up with periods of abject poverty and Camille’s nomadism, and raise their children – three of whom died under the age of 10 – enabled him to paint. Julie even had the good sense to borrow money from Monet behind her husband’s back to buy the house they were renting in Eragny – with the big garden the family loved.

Pissarro: Father of Impressionism is able to go where the exhibition does not or cannot go: providing us with a detailed and rich biographical film and showing us works of art that are not in the exhibition. Thanks to the experts, we also learn about Pissarro’s anarchism (the family were friends with the infamous, marvellous anarchist, Felix Fénéon) and involvement in the Dreyfus Affair (1894-1906) which the exhibition ignores. For although Pissarro was never a practising Jew, the anti-Semites Renoir and Degas turned against the man to whom they owed so much with vile insults about his character and art. They even poisoned the mind of the wealthy Julie Manet, whose late mother, Berthe Morisot, exhibited with Pissarro in all but one of the Impressionists Exhibitions.