What a farce! Well, what else would you expect when a play by France’s foremost comic playwright is rendered into riotous rhyming couplets by Scouser poet Roger McGough? The premiere and subsequent tour of The Hypochondriac were a great success in 2009, as was Tartuffe the year before. And this production? Superb! A joy from start to finish!

Huge hit with extravagant, big-wig Sun King, Louis XIV in the 1660s, Moliere was the first French writer to revolve and spiral his comedies, like Shakespeare, around the quirks, flaws and eccentricities in real human nature. Like the Bard, he also acted in his own plays, ran his own company and had a monarch as patron, and though he didn’t write in verse, he took great relish in words and laughter. Huge hit of 1960’s pop charts three hundred years later was Lily the Pink, co-penned by poet, performer, author, playwright Roger McGough – the one in The Scaffold with the black beatnik specs – who takes even greater relish in words and having a laugh.

Seemingly without effort, the mesmerising flow of words, music, movement and unflagging humour glides smoothly along in light-hearted, uplifting mood, making the darker, more tragic aspects of Moliere’s play much lighter. The physical humour is rarely overblown and rhyme never overlaboured, all serving to do well-balanced justice to McGough’s stimulating, witty script. Watching from the stalls, the man himself, along with the entire magnificent cast, was, naturellement, ultimately rewarded with standing ovations.

Written in 1673, Le Malade Imaginaire satirises Argan, a selfish hypochondriac whose overwhelming, unhealthy fixation on nothing but his health and bodily functions rules and wrecks his own life and the lives of his entire household. By way of social comment (in times before the welcome advent of the NHS – Non -Harmful Surgeons) Moliere mocks, too, the incompetent, greedy quack doctors who preyed on gullible middle-class fools like Argan, lining their pockets at the expense of patients while dispensing all manner of nasty nonsense – enter giant syringes, lengths of tubing, bottles, potions and enemas. Far from being a hypochondriac himself, though, Moliere suffered from very real TB, so much so that even as he performed as Argan he suffered a severe coughing fit and died later that evening. It’s pretty unlikely anyone will ever outdo him when it comes to irony.

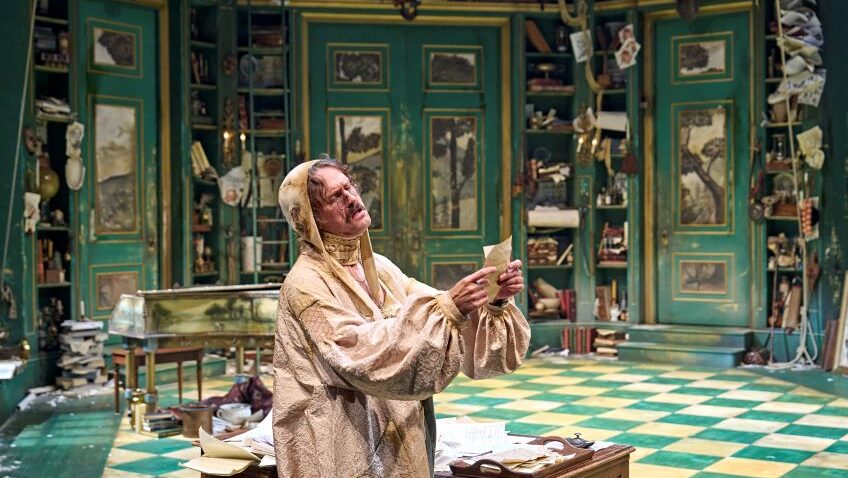

Pace, movement, rhythm and timing are generally spot-on. Silky-smooth delivery of lines, excellent comic timing and sturdy acting skills from a strong, role-doubling cast ensure characters spring to life as credible (yet unbelievable) personalities and not merely caricatures. High praise to Edward Hogg as Argan: as his body droops and stoops, bends and slouches, moans and groans, the glorious physical comedy he delivers enhances the verbal humour while a perky, playful spark lurks beneath. Less odious than Moliere’s man, he’s even likeable despite his crotchety anger and unreasonableness. Bourgeois gents dress, of course, as this production shows beautifully, in elaborate seventeenth century frock-coat elegance; but not Argan: he drops, flops, shuffles and slobs about in shabby bonnet, mouldering linen gown and surgical corset. First seen staring into his chamber-pot after a bout of loud flatulence, he declares with a pitiful sigh, “Rien… je regrette… rien.”

As Argan’s second wife, the villainous Jessica Ransom (most widely known in Doc Martin and Horrible Histories) is splendid in gorgeous, period blue gown. Though she’s a monstrous, heartless gold-digger who deceives Argan into believing she’s a loving wife whilst being desperately keen for him to pop his clogs, Ransom’s wonderful comedic skills make her a thoroughly pleasing villain.

Colin Redmon’s spectacular set, like the costumes, is a feast for the eyes and almost a character in its own right. A cock-eyed, messy clutter of long collected, neglected possessions towers up as far as the eye can see, on shelves and off them, and extends round the perimeter of the thrust stage – ill-stacked books, unruly papers, paintings, diagrams, chalkboard, lamps, ladder, all manner of unkempt odds and tatty sods and a dangling replica skeleton. This chaotic debris nicely reflects the overwhelming, stifling disarray of Argan’s trapped mind (and my loft).

Onstage is an equally messy desk to slouch at, hide behind or crawl and chase through, the odd chair and hip-bath and, of course, a keyboard spinnette. Ballet and music featured large in Moliere’s comedies (especially from friends and collaborators Charpentier and Lully) and we are likewise blessed, at intervals, with musical delights from composer Oliver Birch. Fine treats of instrumentals, songs and harmony evoke both Argan’s era and our own via tinkling period music that’s got big-voiced, modern-genre knobs on. Accordion and violin appear later, likewise played onstage by talented actor/musicians, Andre Erfig (aproned servant and red-coated, wily notary) and MD, Jonathan Ainscough, aptly named since he also plays big, pompous quack Doctor Purgeon as well as aproned servant.

Musical hilarity arises from the “improvised” pastoral song skit between Argan’s Fol-de-Rol daughter Angelique, played lovesick, loving, be-ribboned and bubbly in a big, pink frock by Saroja-Lily Ratnavel, and rock-voiced Cleante, her secret love who pretends to be her music teacher, played by fine-voiced Zak Ghazi-Torbati, a tall, blue elegance whose initial clumsy nervousness is so warm and natural it makes him endearing and brings genuine laughter.

But Argan demands his daughter do her filial duty and marry a doctor for then he can cut his colossal medical bills. Enter ludicrous Thomas Diaforius, Welsh-lilting, lop-haired, fop-haired, boring nincompoop (Garmon Rhys) and his stalwart, Welsh-accented doctor father (Chris Hannon). Rhys causes fits of laughter with his over-the-top, ridiculous flourishes, wordy idiocy and the subtle deployment of his walking cane in a humorous location, while the comic interactions and silly walks of the father-and-son comic duo also delight. Hannon later magically transforms into Argan’s sensible brother, Beralde, in lovely lilac and not Welsh at all. With wise common sense, Beralde is the voice of reason, Hannon giving another very fine performance as he delivers home truths to Argan about his wily wife, his doctors’ devilish quackery and the imaginary poor status of his health.

Another full of sense – and feisty, sharp-tongued, scheming and resourceful besides – is Argan’s chief servant and major player, Toinette, played with beautifully engaging, twinkling verve by Zweyla Mitchell Dos Santos. In wily disguise as a moustachioed Italian doctor, though, she lowers her voice and the evening’s otherwise sparkling clarity of words is briefly lost. Clarity’s essential, of course, not just so we laugh on hearing “I’m agog” rhyme with “to the bog” or “mole on” with “colon”, but so that the entire oeuvre’s subtler, cleverly crafted flow of mots justes delights with continuous treats.

Of course, after three cheers for Moliere (and none at all for Racine or Corneille) everyone ends up singing about a medicinal compound, which is, apparently, most efficacious in every case, and they all live a bit more happily ever after. Heaps of fun with oodles of zut allure!

Eileen Caiger Gray

The play continues at The Crucible until Oct 21st.