Joyce Glasser reviews The Phantom of the Open (March 18, 2022) Cert 12A, 106 mins.

Twelve years before Maurice Flitcroft became the world’s worst golfer with a score of 121 (49 over par) at the 1976 British Open Golf Championship, Bob Dylan opined, “you know there’s no success like failure, and failure’s no success at all.” Some of our top film directors have managed to turn failure into box office success by recognising the appeal of dedicated underdogs who win our hearts. Dexter Fletcher (Rocket Man, Wild Bill) celebrated ski-jumper Eddie the Eagle, who, representing Great Britain at the Winter Olympics in 1988 came last; and Stephen Frears (The Queen, The Grifters, My Beautiful Laundrette) paid tribute to opera lover Florence Foster Jenkins, of whom Stephen Pile wrote, “No one, before or since, has succeeded in liberating themselves quite so completely from the shackles of musical notation.”

Pile, who published The Book of Heroic Failures in 1979 could omit Flitcroft: he was an artful dodger who, as depicted in Craig Roberts’ hilarious biopic, The Phantom of the Open, continued entering competitions under a stream of outrageous pseudonyms like Arnold Palmtree, and always outstaying his welcome.

Unlike Roberts’ under-par features as writer-director, Just Jim and Eternal Beauty, here Roberts wisely lets Simon Farnaby (Mindhorn and Paddington 2), adapt his own funny biography of Flitcroft (written with Scott Murray). Mark Rylance, a master of deadpan humour and loveable underdogs, does the rest, nailing Flitcroft, the 46-year-old crane operator from the Vickers’s Armstrong shipyard in Barrow-in-Furness.

At a loss of what to do with his life with shipyard redundancy looming, Flitcroft has an epiphany while channel hopping late one night and seeing the American golfer Tom Watson’s surprise win at the 1975 British Open. Those who saw King Richard, will recall Richard Williams’ epiphany watching tennis pro Virginia Ruzici win in 1978 – a chance tune-in that determined the future of his unborn tennis pro daughters.

With the help of his supportive wife Jean (Sally Hawkins), ever grateful to Maurice for marrying an ostracised single mother, we watch the Flitcrofts’ hilarious registration to enter the Open, and Maurice’s practice sessions on a windy beach. Even if he could afford the membership fees, there is the cost of the required clothing and the connections with members to be nominated. Then, there’s the waiting list.

Jean, a secretary at the shipyards, handles the forms, but is puzzled by the terminology. For handicap, they agree Maurice should mention his arthritis. By entering “professional,” Maurice can circumvent a lot of troublesome questions, such as the numeric value of his handicap. When Jean is hesitant about his claim to being a professional when he had never played a single game in his life, he replies, ‘You didn’t see me practising this morning.’ To his credit, Flitcroft practised long hours in all weather and anywhere in fact, but on a golf course. He was banned from those after trespassing on the Cumbria Country Club course.

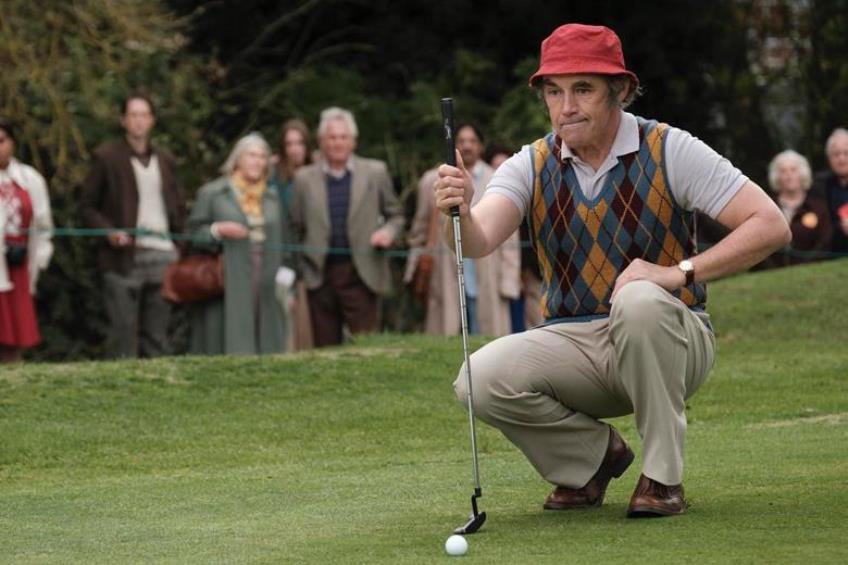

The qualifier for the Open itself takes place at Merseyside’s Formby Golf Club, and Maurice, entering for the first and last time under his own name, has his teenage son Gene caddying. Deadly serious, he tells a reporter, ‘I think my problem today is that I left my four-wood in the car.’ But when his playing annoys the professionals and his score of 121 attracts the attention of R & A governing body supremo Keith Mackenzie (Rhys Ifans), he takes Flitcroft’s unapologetic ineptitude as a personal attack and banishes Flitcroft from the course.

This begins a hilarious (the correspondence has apparently been saved) correspondence between Flitcroft (Jean typing away) and his nemesis. We see the female secretary who was rebuffed and ridiculed for warning Mackenzie about Flitcroft’s suspicious application dutifully typing his replies.

Flitcroft’s stepson, Mike (James Davies, excellent) has become a rising star in the Vickers-Armstrong managerial team, assigned to oversee the change-over. Angry about his stepfather’s notoriety, Mike tells him that skipping work and embarrassing the shipyard with his illicit antics would cost him his job.

While Flitcroft had his fans, including the Blythefield Country Club in Grand Rapids, Michigan, which ran a Maurice G. Flintcroft Tournament for the world’s worst golfer that inspired at least one young man’s successful career in golf, Roberts does not shy away from showing the costs of Flitcroft’s magnificent folly. The family lose their home and Jean and Maurice spend their later years isolated in a cramped caravan.

Mickey becomes estranged from his family, although there is a wonderful scene in which a trio of Japanese investors enquire about the surname that he shares with the golfer, now infamous in Japan. Mickey’s horrified boss instantly denies the connection to save the deal expecting company-man Mickey to do the same.

When Maurice realises he cannot enter another tournament, Jean suggests he use an alias. In 1984 he dons a moustache and enters under the name Gerald Hoppy, a Swiss player. Unfortunately, his caddy friend keeps calling him Maurice and by then, Mackenzie could recognise Flitcroft’s signature on the applications.

The unstoppable Flitcroft, to paraphrase Samuel Becket, “Tries again. Fails Again. Fails Better.” He has three more attempts at the Open, the last in 1990 under the pseudonym Gene Pacecki (as in the pay cheque he never received).

Roberts and Farnaby go overboard in hammering home the heart-warming nature of Flitcroft’s “every dreamer deserves a shot” pursuit, but Hawkins comes to the rescue as Jean who startles a Sun sports reporter (Ash Tanton) when she thinks his high score is great news. Just when you don’t know what is dramatic licence and what is true, we meet the Flitcrofts’ twin sons, Gene and James (Jonah and Christian Lees). They are chasing their own improbable dream of becoming world disco-dancing champions and give us a demonstration.