Listen to Me Marlon is a fascinating, revelatory and unique documentary that premiered in the UK at the London Film Festival two weeks ago and is now on general release. Though considered to be the greatest American actor of the 20th Century, Marlon Brando remained a private man and a professional enigma.

But Director/co-writer Stevan Riley has gained access to a previously unknown archive of audio/visual material compiled by Brando himself that is a cross between a long confessional, self-analysis and hypnosis and an honest, introspective meditation on his personal and professional life.

Ingeniously, Riley uses the contemporaneous tapes, albeit enhanced by film clips, photos and a few short third-party testimonials, to create an autobiography: one that is narrated by the late actor as though from beyond the grave.

The film is a treasure trove for fans of Brando and cinema in general, but it should also be of interest to anyone interested in the human mind. Although Brando did not destroy the tapes, he did not, as far as we know, intend them to be heard by anyone else.

Fortunately, Riley’s brilliant editing and sensitive writing not only enhance our understanding of the actor, but also draw painful parallels between his relationship with his father and with his own troubled son Christian, who died at age 49 in 2008, just four years after his father.

We follow Marlon from a miserable childhood – his alcoholic mother died young, suffering at the hands of his peripatetic, abusive father, Marlon Senior – to salvation through acting. No wonder Marlon considered acting Guru Stella Adler to be a surrogate mother. She invited the handsome, wild, young man to live at her home and, unlike his father who told him he would never amount to anything, recognised and encouraged his talent.

Classified as 4-F by the war office, Marlon benefited from a jump start on his career and by 1944 he had progressed to his first Broadway role.

Classified as 4-F by the war office, Marlon benefited from a jump start on his career and by 1944 he had progressed to his first Broadway role.

In his mid-twenties, Brando exploded on the stage in 1948’s A Streetcar Named Desire. Three years later Tennessee Williams watched in awe as Brando lit up the screen in Elia Kazan’s film production that made Brando a poster boy and household name.

Riley begins to construct a narrative through his editing here as we watch Marlon’s Stanley Kowalski bullying the fragile Blanche Dubois while hearing Marlon talking about how his father ‘used to slap me around, and for no good reason.’ Stella Adler showed Marlon how to put these memories to work in his acting.

Referring to his father’s criticism when he was rejected from the army, Marlon says, ‘I was making more in six months of work than he made in ten years.’ Just as we hear Marlon remember threatening to kill his father if he abused his mother again, we see an odd clip from a 1955 CBS-TV Person to Person interview in which a spruced-up Brando, 30, is standing next to his seated elderly father as though they were posing for a portrait.

Brando had just won the Academy Award for On the Waterfront, and Edward R Murrow, the interviewer, asks Marlon Sr if he were proud. Marlon Sr replies cryptically: ‘Well, as an actor not too proud, but as a man, why, quite proud.’ Marlon Sr also offers a cruel understatement about his son’s upbringing: ‘I think he had probably a little more trouble with his parents than most children do.’

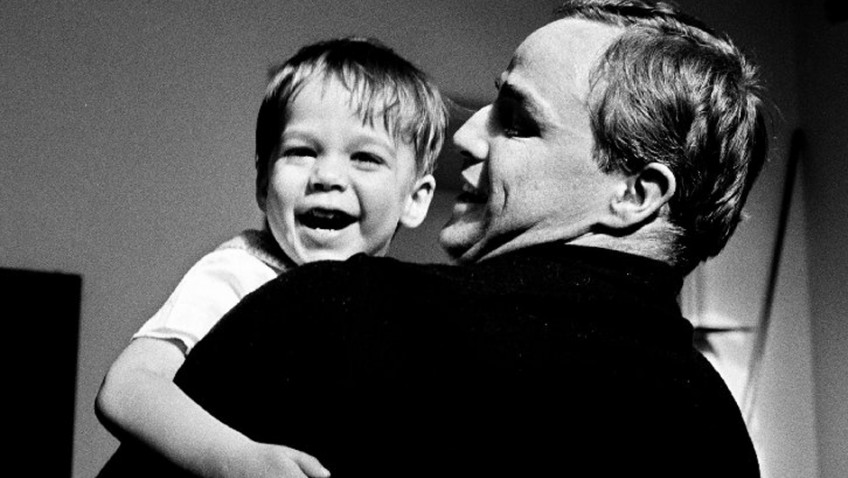

From the triumphant actor and vindicated son, we see the husband (he married Anna Kashfi in 1957) and proud, though neglectful father of Christian. Christian, like his father, grew up in a divided family as his parents divorced a year after he was born. Like his own father, Marlon was generally absent from Christian’s life. He also had a steady stream of affairs (and children).

In 1962 work took him to Tahiti to play the rebellious Fletcher Christian in Mutiny on the Bounty where, it is generally acknowledged, Brando staged his own mutiny, costing the production millions.

While critics blamed Brando’s casting and performance for the disastrous box office, we hear Brando condemn the film industry, including Academy Award winning director (All Quiet on the Western Front) Lewis Milestone.

Life imitated art in another way, too. Riley shows us the scene in which Christian sets eyes on the enticing young native princess Maimiti. She was played by Tarita Teriipaia, whom Brando immediately married despite the nearly 20-year age and cultural gap.

Their ten year marriage (Brando’s third and longest by far) produced a son and, in 1970, a daughter Tarita Cheyenne who grew up in Tahiti, seldom seeing the father she longed to be with.

Sound editing enables Riley to connect background gun shots illustrating Brando’s threat to his father, with the gun shot that sent Christian to prison for killing his half-sister Cheyenne’s boyfriend Dag Drollet.

Cheyenne, 23, was pregnant at the time. Christian served five of a ten year prison sentence while Cheyenne’s mental health disintegrated. Understandably, the most moving moments of the film centre around Brando’s speech at Christian’s trial and his reaction to Cheyenne’s suicide in 1995, age 25.

This overview of Brando’s enthralling life, enhanced by wonderful clips and stills, is reason enough to see the film, but Riley’s reveals that despite his apparent success, Brando’s lifelong struggle with his inner demons sabotaged his chance at happiness as he, no doubt subconsciously, repeated the sins of his father.

Behind the actor who, in later life, was deemed a greedy, unreliable, uninsurable ego maniac, was a sensitive, intelligent and probing mind searching for a meaning to life, and to the profession that he elevated to a new level.