Joyce Glasser reviews The Shining (October 31, 2017) Cert. 18, 119 min.

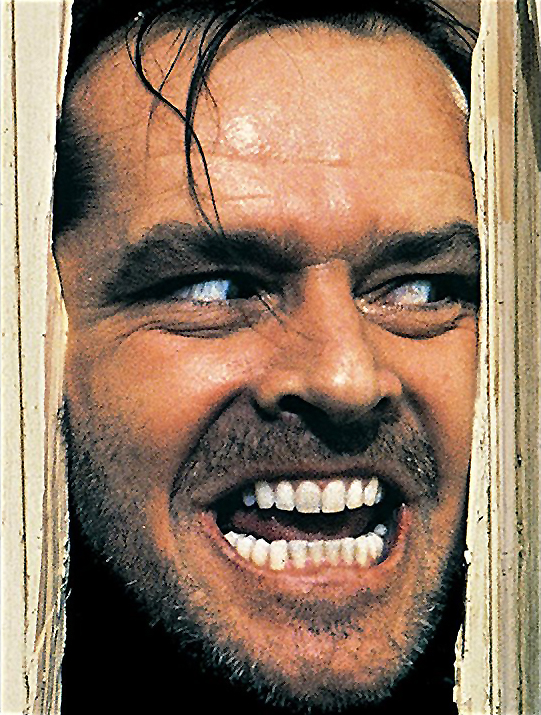

Re-released for Halloween, Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining, considerably edited to its final version after its first, much criticised release in 1980, has become more than a cult hit. Despite Stephen King’s harsh criticism, it has become a reference point for many horror movies that followed because no one can shake its haunting images from their mind, and not just the Freudian kind.

Kubrick’s daughter Vivian made a ‘The Making of the Shining’ documentary that aired on BBC and in 2012, the documentary Room 237, presented various conspiracy theories and a case for coded symbols referring to the Holocaust – amongst others. In fact, the original room number for the film’s historic Brady family tragedy was 217, but it was changed after the manager of the Timberline Lodge, in Mount Hood Oregon, where exteriors of the film were shot, appealed to Kubrick in a letter:

It is very probable that once the movie is released and known locally, we might have serious difficulties renting our Room 217 as some of our guests could be afraid of being chased by the bloated body of the bath-tub lady. If at all possible, Dick would like you to change the number of 117 to 237, 247 or 257, neither of which exists at Timberline Lodge.’

The plot should by now be familiar to almost everyone. Jack Torrance (Jack Nicholson), a would-be writer and recovering alcoholic in Denver, takes a job as an out-of-season caretaker at the Overlook Hotel in the Canadian Rockies (though the film was made at EMI Elstree Studios and four other locations in Southern England). Jack is warned about the effects of the long, lonely, snowbound, dark winters and the fate of a previous off-season caretaker, Delbert Grady (Philip Stone), his wife, and their twin girls (Lisa and Louise Burns appear in the short documentary).

Within a short time Jack is terrorizing his wife, Wendy (Shelly Duval) and young son, Danny (Danny Lloyd). Danny has an imaginary friend who is much more alarming than most. For Danny possesses what departing hotel Chef Hallorann (Scatman Crothers) recognises as ‘the shining’: a psychic ability to see – in this case, the hotel’s grim past – and to relate the past to the present.

In 1980, director and co-writer (with novelist Diane Johnson) Stanley Kubrick was 52, and the height of his fame. The film’s star, Jack Nicholson, was 43 and at the height of his incredible career. That year was arguably the pinnacle of 28-year-old Shelley Duval’s film career: Robert Altman’s Popeye, in which Duvall co-starred, was also released in 1980. She remained active in television for a time before retiring, allegedly due to mental health problems. The Shining marked the beginning and the end for the incredible six-year-old first-time film actor Danny Lloyd, who was never to make a feature film again. Despite telling an interviewer that he was unaware he was making a horror movie at the time he is now a biology teacher in a community college in Kentucky.

Witness accounts of Kubrick’s obsession with his first real horror film can leave you wondering to what extent the director’s perfectionism was a factor in the fate of Duvall and Lloyd. In the documentary Stanley Kubrick: A Life in Pictures Nicholson stated that Kubrick, whom he found ‘great to work with’ (Nicholson was allowed to improvise extensively), ‘was a different director with Duvall.’ They had arguments on set (to the extent that her hair began falling out) and it seemed to witnesses that he intentionally isolated her from the rest of the cast and crew.

Principal photography lasted a year, an unheard of length of time that would have taken a toll on any actor. But if Duvall was forced to cry hysterically while swinging a baseball bat at her screen husband 127 times before Kubrick was satisfied, imagine the toll on a six-year-old of repeating a dark kitchen conversation about his supernatural gifts with Chef Hallorann 148 times, day after day.

But Nicholson was not immune to what was apparently Kubrick’s way of antagonising the actors to put them in the right psychological frame of mind. Apparently the script changed so often that Nicholson, duly frustrated, stopped reading the drafts, let alone learning the lines, until the very last minute.

If the film is remembered for the inordinate duration of principal photography (an entire year) and for the demands on cast and crew, it is also remembered for the remarkable and pioneering use of the newly-invented Steadicam. In Matt Wells’ 7-minute documentary, ‘Work and Play: a short film about the Shining’, which will be shown before the feature, Steadicam operator Garrett Brown talks about how the camera freed the director from dolly tracks and static tripods. Kubrick used it to disorientate the viewer as well. He turned it upside down so that it creeps along the floor of the corridors and, with wide angle lenses, the corridors or lanes of the maze loom up over the viewer.

But most of all we remember The Shining for its haunting images which, like those of a dream or a nightmare, speak to our sub-conscience and remain lodged in our mind’s eye. The blood gushing out of the elevator doors; the Grady girls inviting Danny to play; the pages of Jack’s manuscript that Wendy discovers next to his typewriter; Danny’s rides along the corridors and his footprints in the snow-covered maze; the 1920’s bar and restaurant; Lloyd the bar tender (surely the model for Michael Sheen’s android bartender in 2016’s Passengers); the food store room; Harroran’s Florida home; the snowcat; the bloated lady in room 237 – and the hotel itself, a central character and the epitome of the haunted house that is now embedded in our psyche.

You can watch the film trailer here: