Joyce Glasser reviews The Red Turtle (May 26, 2017) (PG)

The Dutch born, London-based writer/animator/animation director Michaël Dudok de Wit could be the most talented paradox in the film world. His animated films are so non-commercial that his first four were shorts; full of gorgeous 2D line drawing, but with no dialogue. Yet Dudok de Wit has made his living in the very commercial world of advertising and television animation. His third short, Father and Daughter won an Academy Award, making it the perfect calling card for a feature film with a sizeable budget. Yet it has taken him 17 years to release a feature. That said, clocking in at 81 minutes and with no dialogue, Dudok de Wit has once again defied what we call mainstream cinema. And while young directors are chomping at the bit to make their first feature, Dudok de Wit, though he is now 63, had no such ambition. It was only when Japan’s famed animation house, Studio Ghibli, approached him that Dudok de Wit came up with the idea for what became the Academy Award nominated, The Red Turtle.

The story is as deceptively simple as the gorgeous, graceful 2D animation (which co-writer and director Dudok de Wit did not do this time around). The plot might strike you as a cliché as it is a castaway movie, you know: the victim of a ship wreck ends up alone on an uninhabited island and learns to survive while trying to escape. But if you are imagining scenes from Cast Away, Blue Lagoon, Swept Away or even Robinson Crusoe, think again.

The film opens with a young man caught in a storm at sea although the depiction of the thunder storm is so real – despite being animated and in black and white – that you feel you are caught in it. The sound effects in particular are astonishingly real. The next morning the young man finds himself washed up on shore and disorientated. Unlike in many castaway films, this island has an abundance of fresh water, food, warm weather and wood, although, as we see when he slides down a cliff into a hidden pool, it is not without danger. Once you are caught in Dudok de Wit’s spell, you won’t ever doubt that uninhabited islands can still exist in a world where celebrities buy their own little islands and no part of the globe is left unexplored.

The man sets about making a raft to escape, all the while accompanied by a group of curious little crabs that are so adorable they bring a smile, if not some laughter. Still, the creatures are also very real in the way in which move and interact with their environment.

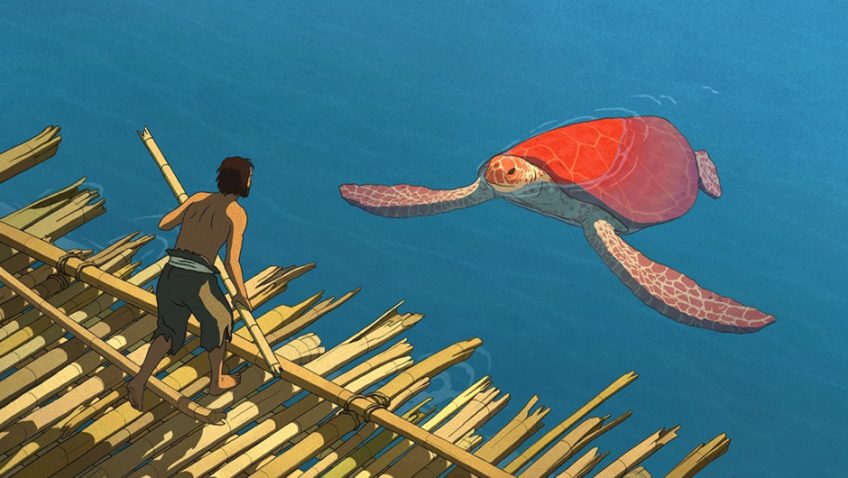

Each time the man sets out to sea on his substantial raft, something sabotages it from underneath and breaks it apart. Frustrated and furious, the man can only start again. On the third venture, the man discovers the impediment. He sees a giant red (the first appearance of colour in the film) turtle approaching the raft and they engage in a staring match. The man attacks the turtle and stomps on it, leaving it to die on its back on the beach.

To draw a comparison with the sailor who kills the albatross in Samuel Coleridge’s ballad would be too heavy handed, but, full of remorse, the man returns to the dead turtle the following day. Along with the contrite man we witness one of nature’s more astonishing metamorphoses.

To draw a comparison with the sailor who kills the albatross in Samuel Coleridge’s ballad would be too heavy handed, but, full of remorse, the man returns to the dead turtle the following day. Along with the contrite man we witness one of nature’s more astonishing metamorphoses.

For this film, the animators used digital pen for the characters and charcoal on paper for the background, digitally creating only the raft and turtles (yes, more appear later on). While the raft and turtles were digitally created, they blend in seamlessly. The music, the characters’ breathing and other occasional sounds are rare, but so expressive that you never miss the dialogue.

How can a film with three characters, no villains, and after the first twenty minutes, no unusual obstacles, sustain itself and keep our interest? The question does not really crop up while you absorbed in the story and its style: an exercise in the elegance of simplicity. In an interview, the director states that he did not want to show how the man survives as that is usually the focus of castaway films. The Red Turtle is more about why the man survives. This involves the cycle of life itself and the mysteries of birth, childhood and death.

While Dudok de Wit and the animators researched nature carefully, with the film’s subtle touches of magic and mystery, it is hardly a nature documentary. Nor is it a conventional mystery story. We know nothing of the young man’s life before he survived the storm at sea and landed alone on the island. Was he a fisherman? Was he on a honeymoon cruise or in a yacht race? Or was he an escaped convict?

The turtle is transformed – at least temporarily – and you could say that the man has conquered nature and is now free to escape. But while the man’s initial hostility to the turtle is also transformed, the animal nonetheless exerts a hold on its killer. We are left to ponder on the nature of free will when the man no longer seeks to leave once the main obstacle to his escape is removed.

Nor can we prevent ourselves thinking of how his life would have been had he escaped. He might have died at sea, or he might have gone on to be reunited with his family and to enjoy the richness of the culture and society in whatever country he lived in. But what is remarkable is how much we grow to care about him throughout the course of the film, without ever hearing him speak or knowing his thoughts. Like Father and Daughter, it is a tour de force in animation and in capturing the workings of the human heart.

You can watch the film trailer here: