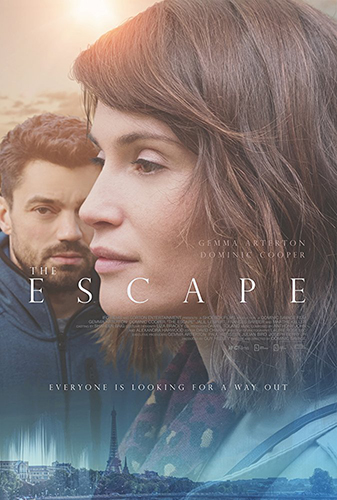

Joyce Glasser reviews The Escape (August 3, 2018) Cert. 15, 101 min.

Gemma Arterton is a curvaceous beauty and can be a good actress, too, although her recent career has not been helped by starring roles in films like Their Finest, The Girl with all the Gifts and Gemma Bovary. She landed a glamour role, too, playing one of the less memorable Bond Girls in Quantum of Solace. The Escape, written and directed by British television director Dominic Savage, is a platform for Ms Arterton to show us her impressive acting range. Arterton is in every single shot, and many of those are of spontaneous tears, proving that she is in touch with her inner character. There are no period details, spies or Sci-Fi apparatus to distract us either, as this pared down, small scale drama traps its makeup-free heroine in an unglamorous cocoon and then lures her out into the big, indifferent world.

An opening bookend device aside, for nearly the entire first half of the film Savage takes us through the mundane life of a wife and mother who remains nameless for some time, as though she has lost her individual identity. At first cinephiles might be mistaken for thinking that Savage has adapted Chantal Akerman’s Jeanne Dielman, 23, Quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles to modern day suburban Kent. But Savage’s depiction of oppressive ennui, is less artful and we, too, are eventually clamouring to get out.

An opening bookend device aside, for nearly the entire first half of the film Savage takes us through the mundane life of a wife and mother who remains nameless for some time, as though she has lost her individual identity. At first cinephiles might be mistaken for thinking that Savage has adapted Chantal Akerman’s Jeanne Dielman, 23, Quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles to modern day suburban Kent. But Savage’s depiction of oppressive ennui, is less artful and we, too, are eventually clamouring to get out.

An alarm rings and Mark (Dominic Cooper), a good-looking man approaching 40 wakes up next to a pretty 30ish, woman: his wife (Arterton). We later learn her name is Tara. When he snuggles up to her as a prelude to a morning ‘quickie before work’, she turns away. When he pleads, she grimaces, but gives in because she does not have the will to send a stronger message.

When Mark emerges from the shower, he complains that the towels are not laid out for him. ‘I’m at work all day; I can’t do the laundry,’ he reminds her, as though there are not millions of people who manage to do both every day. Downstairs is a frenzied breakfast with two adorable kids (Teddy and Florrie Pender) and the school run. Then it’s time for the supermarket. In the car park the woman watches a mother with a child load the boot with plastic bags. Tara has six. Saving the planet is not high on this suburban mother’s agenda. But can she save herself?

It’s soon time to collect the children, prepare dinner and, in bed, submit to her husband – still enthusiastic about sex after nearly a decade of marriage. He either pretends not to notice, or somehow does not, that she is not responsive. Yet it’s clear to us that she feels trapped in a family that gives her no pleasure and joy.

Her single mother (Frances Barber) is, like Mark, unable or unwilling to read Tara’s messages and cries for help. She reassures Tara that ‘it’s just a phase’. She tells her, with a hint of jealousy, ‘you have it made… You have two cars and a beautiful house. I had to do it all on my own!’ Tara has a husband who makes a good living; he is not violent, does gamble or come home drunk and is a loving father.

Escape is at first a trip to nearby Ashford, Kent, where she parks the car and watches the Eurostar trains head for Paris. The antithesis is a typical Sunday afternoon in the garden where Mark is entertaining friends at a barbeque. Tara is visibly bored and removed. That night after passionless sex, she bursts out in tears and tells Mark, ‘I’m not happy.’ Mark can only reply: ‘Did I do something wrong?’

Escape is also, at first, a day out in London where she purchases a book on the Lady and the Unicorn tapestries that are in fact in Paris. When she tries to discuss her find with Mark, the best he do is humour her enthusiasm with a marked absence of interest. When her son accidently damages the book, she explodes, as though he is literally responsible for destroying her dreams.

The trouble here is that while Mark’s insensitivity is all too apparent, it’s difficult for the audience to take Tara’s newfound passion seriously either. With no evidence Tara has sought to indulge her interest in art before now, is she just one more woman (and one who lacks an MA or PhD) whose dream job is working in the arts or creating her own?

After a particularly frazzled breakfast leading to an argument, Tara packs her bag and heads to Paris to see the real Lady and the Unicorn tapestries. Just as plaintive violin strings overwhelm us in the UK, a redundant dose of angelic choir music does so in the museum. Not only is it clichéd, but it’s all wrong for the tapestry and the situation, which hardly need this external boost to tell us what Tara is feeling.

After a romantic encounter with a suspicious photographer in the museum, Tara unravels in her newfound freedom and guilt. The music, tone and look of the film alter dramatically when Tara arrives in Paris to a surge of pianos. Cinematographer Laurie Rose substitutes the crisp, flat-coloured, utilitarian style of the British segments with a melting kaleidoscope of coloured lights as the bustling Parisian streets blur and spin, enveloping a distressed woman. Before we know it Tara is recovering in a splendid apartment on one Paris’s most expensive squares and a sympathetic older lady (Marthe Keller) – who speaks fluent English – is feeding her soft words of wisdom about the need to make contact with Mark.

This cut from night to day is so disorientating that you find yourself wondering what you missed before a bit of expository dialogue fills in the missing information: ‘you looked too unhappy to pass by’ the lady tells Tara, and you think, finally, someone has noticed! But if this benign wealthy lady picks up stray tourists and brings them home, she must be running Europe’s only unlicensed, luxury hostel.

If the second half of the film feels anti-climactic, despite the romantic frisson, so too is Savage’s failure to use The Lady and the Unicorn, with its tantalising interpretations, as a perfect metaphor rather than a rather a facile plot devise.

Where The Escape succeeds is in getting under Tara’s skin as a romantic soul who married too young and now feels trapped in the material comforts of an insufferable, but superficially ideal, marriage. Tara’s breakdown is skilfully executed by Arterton who is more convincing as a modern day Madam Bovary here than she ever was in Gemma Bovary.

You can watch the film trailer here: