Joyce Glasser reviews Mrs Lowry & Son (August 30, 2019), Cert. PG, 91 min.

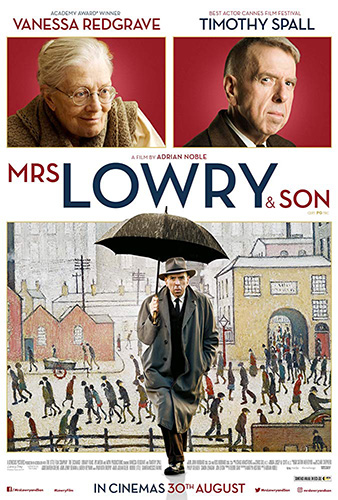

Mrs Lowry & Son is based on Martyn Hesford’s Radio 4 play and neither Hesford, as screenwriter, nor theatre-turned-film director Adrian Noble, can shake off the film’s provenance. The performances of Vanessa Redgrave, 82, as the abusive, but vulnerable social snob Elizabeth Lowry and Mr. Turner star Timothy Spall as her long-suffering, full-time carer son, “Laurie”, make up for many an awkward turn in the film, not the least of which is Lowry’s visit to the Lowry Centre (opened in 2000) in Salford.

The film begins with a close up of Spall (an amateur painter in his own right), bearing the same resemblance to L.S. Lowry as he did to J.M.W. Turner, standing in the rain in that industrial redbrick landscape familiar from his paintings. He stares at the camera and declares: ‘I paint what I see. I paint what I feel. I’m a man who paints, nothing more, nothing less.’ This refrain will be repeated on two further occasions as it is based on a real Lowry quote.

The film begins with a close up of Spall (an amateur painter in his own right), bearing the same resemblance to L.S. Lowry as he did to J.M.W. Turner, standing in the rain in that industrial redbrick landscape familiar from his paintings. He stares at the camera and declares: ‘I paint what I see. I paint what I feel. I’m a man who paints, nothing more, nothing less.’ This refrain will be repeated on two further occasions as it is based on a real Lowry quote.

Most of the action takes place in the Lowrys’ kitchen, in L.S.’s upstairs studio, or on the first floor, in Mrs Lowry’s bedroom, where her son, after preparing their tea, shares the meal with his bed-ridden mother. We do not know what is wrong with her, but we do learn that Dr Mills provides her with happy pills and that the husband she does recalls with little affection has predeceased her, leaving debts.

There are some external shots of L.S. Lowry playing with the neighbourhood children, and one or two shots of a neighbour, Mrs Stanhope (Wendy Morgan), who is one of the few people Elisabeth Lowry approves of. Mrs Stanhope “is immaculately dressed,” suggesting a kindred spirit, and she does not get on with her husband who lacks her refinement.

Through heavy doses of expository writing and characters talking aloud to themselves for our benefit, we learn that this oedipal battle is set in 1934, twenty-five years after Mrs Lowry was condemned to the working-class purgatory of Pendlebury, an industrial district of Manchester, by her husband’s failings. She looks back nostalgically to her piano playing days in the upmarket Victoria Park area and tells us that she dreamt of being a concert pianist and practised every day. Her aspirations apparently diminished with her health.

We learn that Lowry is dutifully paying back his father’s debits, although, in a clever bit of information giving, Mrs Lowry snaps, ‘How are you going to do it on a junior clerk’s salary with no promotion in 25 years?’ From this exchange we learn that Mrs. Lowry will find any reason to put her son down and that Lowry is less ambitious with his career as a rent collector – which he continued until retirement – than he is with his art.

While his mother bemoans her surroundings, Lowry has come to find beauty in the industrial landscapes of Pendlebury that were his making. He does not care about the mean-spirited criticism, but his status-conscious mother would rather read the critics than look at the paintings herself. We are treated to many of the reviews she reads out loud, one of which calls Coming from the Mill, “an insult to the people of Lancashire.”

Embarrassed at the criticism of his “squalid” mill scenes and “matchstick men” figures, she pleads with her devoted son to ‘give it up; you’re not an artist and never will be.’

It is understandable, therefore, that Mrs Lowry is suspicious when the critically maligned Coming from the Mill attracts the attention of a London gallery owner. We see Lowry opening the envelope and hiding it in the cupboard, and then finally plucking the courage to tell his mother. ‘If he likes what he sees, I’ll have an exhibition in his galleries’, Lowry announces gingerly.

Instead of being proud of her son, she warns him that pretentious people make all sorts of promises, adding that ‘everything depends on whether he can be trusted.’

One person Elizabeth Lowry does trust is Mrs Stanhope who, when she stops by for a fundraising campaign, mentions that she admires Lowry’s Sailing Boats, and to Lowry’s surprise, his mother asks to see the painting (which she had removed from her bedroom when he originally gave it to her as a gift). Mrs Stanhope’s opinion causes Mrs Lowry to look at the painting anew and in it she finds the memories of her happy times with young Laurie on the beach. In a touching moment, sitting side by side on Elisabeth’s bed, they both stare at the painting and she murmurs, ‘life at the beginning had so much promise.’

Caught somewhere between Mommy Dearest and Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?, the sparks fly but the film never ignites. Redgrave is terrific, and her Mrs Lowry is outrageous, delivering her insults right to the jugular, but knowing when to retreat. Just why Lowry takes the abuse is unclear as he goes way beyond a dutiful son. It is only in a coda that we learn that Lowry really did paint to impress his mother. He rejected a knighthood in 1968, presumably because after his mother’s death in 1939, such high-profile recognition had no meaning.

It is a shame that we gain little insight into Lowry’s work or the impact on his art of his lifelong, co-dependent relationship with his mother. Lowry never married or, apparently, dated, but he did, it seems, make friends with young girls. Carol Ann Lowry is not a daughter, but an adoptive goddaughter who was left the rights to his archive.

During the seven years after his father’s death that Lowry cared for his mother, he began painting his “horrible heads” one of which is shown at the end of the film in the Lowry Centre that show some psychological expressionism. But the filmmakers disregard a cache of erotic canvases that were found in his studio after his death that express a deep sexual anxiety that might have shed some light on a missing dimension of this deceptively “naïve” painter’s life.

You can watch the film trailer here: