Joyce Glasser reviews Manifesto (November 24, 2017) Cert 15, 101 min.

When Cate Blanchett took on the role of iconic singer/songwriter Bob Dylan in Todd Haynes’ thinly disguised 2007 biopic I’m Not There, there was no doubt that the two-time Academy Award winning actress could do anything. The question was, rather, where could she go from there? Not one to rest on her laurels, the 48-year-old actress is pushing the boundaries of acting once again in a film that, fittingly, is pushing the barriers of the feature film genre.

Don’t let the initial scene in which Cate reads from The Communist Manifesto put you off. As arts institutions around the world are commemorating the Russian Revolution this year with art, music, poetry, film and fascinating stories from history, so Manifesto began in an arts’ venue as a multi-screen installation created by Julian Rosefeldt, a Berlin based conceptual artist. Its adaptation to screen is as daring as anything promulgated by Marx and Engels, and if it’s equally challenging, it’s much more visually inventive and mesmerizing.

Don’t let the initial scene in which Cate reads from The Communist Manifesto put you off. As arts institutions around the world are commemorating the Russian Revolution this year with art, music, poetry, film and fascinating stories from history, so Manifesto began in an arts’ venue as a multi-screen installation created by Julian Rosefeldt, a Berlin based conceptual artist. Its adaptation to screen is as daring as anything promulgated by Marx and Engels, and if it’s equally challenging, it’s much more visually inventive and mesmerizing.

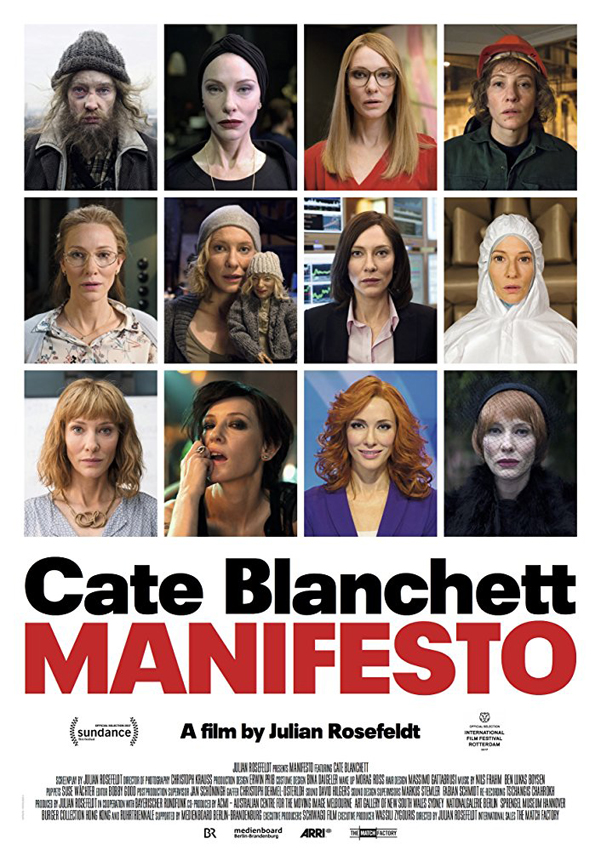

And then there’s Blanchett. If Alec Guinness is partly remembered for having played nine members of the D’Ascoyne family in Kind Hearts and Coronets, Blanchett will undoubtedly be remembered for her thirteen roles in Manifesto – all so different that you might have to convince yourself the woman is not a new species of chameleon who changes a lot more than her colours. She is also very funny.

Manifesto is not going to spoon-feed you its dogma, and if you are not willing to sit back and enjoy being baffled, this might not be for you. For even if you know your Futurism from your Suprematism and Constructivism; and your Vorticism from your Surrealism and Spatialism, you have to adjust to Rosefeldt’s personal rendering and reinterpretation of these movements and their manifestos.

If you’ve ever visited the Estorick Collection in Islington, you will know all about Futurism. That movement had a famous manifesto written and published in Milan and Paris in 1909 by Filippo Tommaso Marinetti. A poet who inspired many of the finest Italian painters of his day to join the reactionary movement, Marinetti celebrated Italy’s progress as a 20th century nation and used industry, in particularly the car industry, and speed in general as a symbol of modernity. If the nationalism behind his manifesto worried the French artists of the period, the Manifesto’s glorification of war in Article 9, pretty much killed off the movement which did not survive WWI. To represent this movement, Blanchett is a Broker in a busy stock exchange. What could be more apt – or more bizarre?

If Article 10 of the Futurist Manifesto states: “We want to demolish museums and libraries, fight morality, feminism and all opportunist and utilitarian cowardice…” For the international Dada movement, ‘Dada means nothing’. The horrors of the First World War had turned the world upside down and to express this sensation in art, the art had to be as nonsensical as the war. Hugo Ball, the writer of the first Manifesto, read in Zurich in 1916 did not want DADA to be turned into an artistic movement, but it was – thanks to avant-garde poet Tristan Tzara and his followers, Hans Arp, Max Ernst Marcel Duchamp, Salvador Dali, Man Ray, and Hannah Hoch amongst others. Here, as in Communism and Futurism, it is the wordsmiths who create the manifestos and painters, sculptors and photographers who develop it.

‘The magic of a word—Dada—‘Tzara wrote, ‘which has brought journalists to the gates of a world unforeseen, is of no importance to us.’ For this section of the film Blanchett, arriving at a traditional, rural European outdoor funeral, begins reciting the manifesto as part of her funeral oration, drawing on poet Paul Eluard’s Five Ways to Dada Shortage or two Words of Explanation; poet Louis Aragon’s Dada Manifesto and Richard Hulsenbeck’s First German Dada Manifesto of 1918.

Surrealism follows, and while you might think you will find your feet here, Blanchett’s Puppeteer (inspired by André Breton’s Manifesto of Surrealism) and puppet – a Blanchett clone – are, well, a bit surreal. Rosefeldt seems to link Surrealism with Spatialism, Lucio Fontana’s 1947 art movement intended to synthesize colour, sound, space, movement and time into a new type of art. In the creepiest segment, Blanchett, a mother solemnly pontificates around the dining room table of their strangely furnished home as though she were saying grace. Her patient husband and children look on and the food gets cold.

Two of the best segments are saved for last. To express Conceptual Art and Minimalism, Blanchett is a well-dressed studio anchor woman firing off questions about conceptual art to a newsreader on location in a violent storm (also played by Blanchett). This segment uses conceptual artist Sturtevant’s 2004 Shifting Mental Structures (‘man is double, man is copy, man is clone’) lecture and painter Sol LeWitt’s Sentences on Conceptual Art of 1969.

In the hilarious final segment Blanchett is a primary school teacher teaching the Dogma 95 rules to her well-behaved students before giving them a chance to show off their creativity using the rules. She walks down the aisles of the classroom correcting the students, using bits of filmmaker Jim Jarmusch’s Golden Rules of Filmmaking, Werner Herzog’s Minnesota Declaration and. Of course, the Dogma 95 Manifesto created by Danish filmmakers Thomas Vinterberg and Lars von Trier’s, Like most art movements, Dogma 95 was a reaction to the status quo in this case, big budget Hollywood films.

Blanchett’s characters cover the gamut without regard to nationality, gender, age, religion or social status. If some of her characters are fanatics, such as her homeless man shouting nothings from a rooftop, it is a fair commentary on manifestos, which are, after all public proclamations of aims and policies, many of which prove chimerical, self-serving, limited and limiting. Unlike politicians who depend on manifestos for votes, artists usually do not like to classified and labeled. Rosefeldt’s manifestations are full of these contradictions and while not an outright parody of manifestos, certainly one of the most creative responses to them that you will ever see.

You can watch the film trailer here: