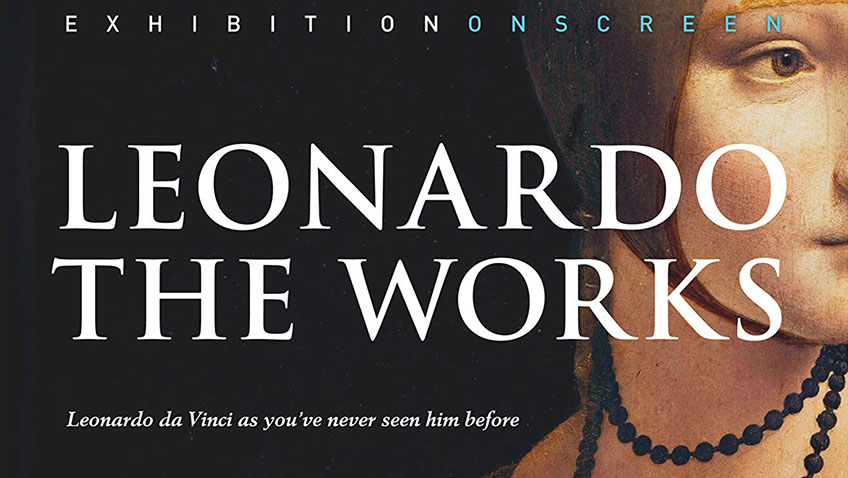

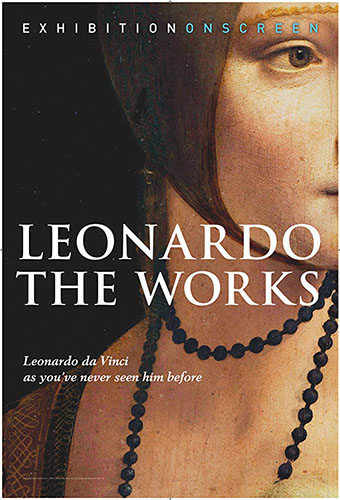

Joyce Glasser reviews Leonardo: The Works (Exhibition on Screen: Tuesday, 29 October), Cert. U, 102 min.

Phil Grabsky’s Exhibition on Screen series normally delivers a documentary around a specific exhibition for those who cannot travel or would like to benefit from the commentaries from experts that you would never find on an audio-guide. But for several reasons, Leonardo: The Works is not an exhibition at all but an edifying, entertaining and accessible art history lesson that captures, in high definition and examines with the benefit of experts the 22 extant paintings attributed to his hand.

The first reason why Grabsky’s film is not focusing on a specific exhibition is that 2019 marks the 500th anniversary of the death of his great painter and polymath. Every institution that owns a Leonardo da Vinci wants to show it off, and as Leonardo completed fewer paintings than Vermeer, no one has an extra one to spare.

The first reason why Grabsky’s film is not focusing on a specific exhibition is that 2019 marks the 500th anniversary of the death of his great painter and polymath. Every institution that owns a Leonardo da Vinci wants to show it off, and as Leonardo completed fewer paintings than Vermeer, no one has an extra one to spare.

Even if the institutions in the UK, France, Germany Italy, Poland, the USA and Russia that are lucky enough to own a painting attributed – even in part – to the Renaissance genius would lend a work, there are simply not enough to go around. So, Phil Grabsky, with David Bickerstaff and Hugh Hood, went around the world filming, in high definition, every extant painting that bears the brush of Leonardo.

Just why Leonardo’s output of paintings – and the completed paintings are even rarer – is so small is addressed in the biographical portions of the film that are sparing, but always enlightening. When Leonardo went to work for a princely fee for François I, he was appointed “First Painter, Engineer and Architect to the King.” Some of his appointments did not include painting at all, opting for Leonardo’s expertise in designing military defences and bridges. He abandoned a July 1481 contract with the Monks of San Donato in Scopeto for an Adoration of the Kings (Magi) when he fled to Milan. He was not just fleeing from the debt for the unfinished painting, but rushing to the vibrant city of Milan where, he knew, the flourishing art scene offered him greater freedom of expression.

Evelyn Welch, Professor of Renaissance Studies at Kings College, London tells about Leonardo’s job application when he learned of a job opening with the powerful Ludavico Sforza. Leonardo stressed his skill at architecture, bridges, military machines, etc, and added, as a postscript, ‘by the way, I can paint as well.’

But Robert Hollingworth of University of York tells us that his posting from Florence to Milan was more related to Leonardo’s musical skills than anything else. Leonardo apparently played the lira da braccio, a kind of Renaissance violin, better than any of the musicians at the Milanese court. Leonardo drew parallels between the rhythm of painting and music and wrote, ‘if painting is science made visible, then music is science made audible.’ Grabsky includes, of course, The Musician (The Singer) from 1481-85, from the Pinacoteca Ambrosiana in Milan and a wonderful reading by Glen McCready from Leonardo’s writings in which he compares music (the second sense) and painting (the first sense).

All of this gives you an idea of why, according to Vasari, on his deathbed, lying in the arms of François 1, Leonardo regretted that “he had offended against God and men by failing to practice his art as he should have done.” Whether he was referring to painting is not known. As the recently concluded exhibition of Leonardo’s drawings at the Queens Gallery, London, showed, his drawings served as his laboratory, providing a good idea of his many unrealised projects and of his many interests including sculpture, anatomy, engineering, cartography and geology.

Leonardo was born out of wedlock to a peasant girl in the hilltop town of Vinci outside of Florence in 1452, but his father, a wealthy legal notary, did not disown his son. When Leonardo was 14, his father took some of Leonardo’s drawings to his friend, the famous painter Andrea del Verrocchio, for his opinion. Verrocchio was astonished and, recognising the boy’s talent, if not yet his genius, invited Leonardo to become his apprentice in his workshop.

The film traces Leonardo’s progress through his apprenticeship. In the Baptism of Christ (1475-76), now at the Uffizi Gallery, Leonardo apparently worked with his master on the angel, which, commentators agree, is better than anything done by Verrocchio. Cecilia Frosinini, a Florentine conservator and art historian tells us that the long, rectangular Annunciation (1472-73) also at the Uffizi, has to be seen as the culmination of Leonardo’s apprenticeship where he dazzles with, as Martin Kemp from Trinity College, Oxford points out, the perspective of Mary’s house; sculptural draperies; angel’s wings modelled after his observations of a bird, and a carpet of flowers full of symbolic life, vitality and perhaps hints at the garden of Eden.

Frosinini points out another, final reason for Leonardo’s low output. When experts were studying the changes Leonardo made in this (and other) paintings, it seems that the painting expresses his need to challenge himself. ‘It’s more a dialogue with himself than with the rest of artistic society.’

Among the most enthralling paintings and analyses are Portrait of Lucrezia Crivelli, (1498) – known in English as Lady with an Ermine – the cultivated mistress of Sfroza. The beautiful, stylish young woman does not look at us directly, but is captured in motion, as she seems to turn to a presence to her left, suggesting that she only has eyes for her lover. Other highlights include Saint Anne, the Mona Lisa and the astonishing application of the concept of the spiritual and the physical in the divine that Leonardo expresses with light and shadow in Saint John the Baptist, all paintings Leonardo brought with him to France.

But no film about Leonardo would be complete without the two versions of his masterpieces, The Virgin of the Rocks and here, the lingering camera and the enlightening commentary do not disappoint. The two paintings are identical save for certain key differences that you will be contemplating if you have the opportunity to see both paintings first-hand. The Louvre’s Leonardo exhibition opens today and the National Gallery’s exhibition, that focuses on the Virgin of the Rocks, opens on 9 November.

You can watch the film trailer here: