Joyce Glasser reviews Inversion (Varoonegi) May 19, 2017

What most of us know about society in Tehran and Iran in general is what we have seen in the films of Iranian filmmakers such as Jafar Panahi, Asghar Farhadi, Mohsen Makhmalbaf and his daugther, Samira. We instinctively thank our lucky stars that we live in London and not Tehran. But London and Tehran have something in common that affects everyone and is unrelated to nuclear weapons or religious ideology. Both cities are plagued by fatally high levels of air pollution.

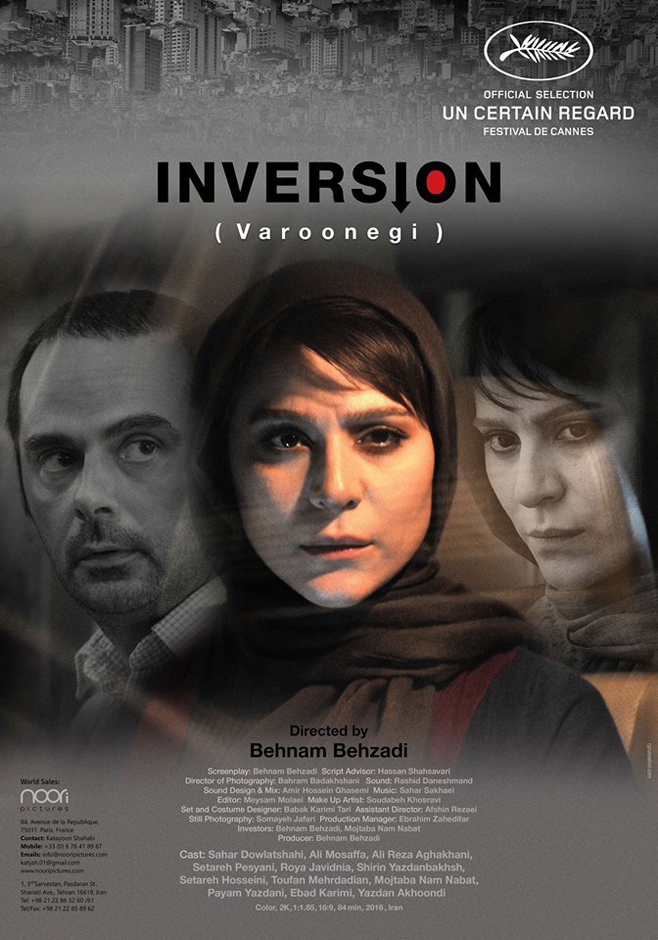

Behnam Behzadi’s revealing slice-of-life family drama uses a panoramic image of the city obscured by smog as its establishing shot. The metaphorical title refers, in the first instance, to thermal inversion caused by warm air settling over cooler air that traps the harmful particles in the atmosphere close to the ground. But it is the intricately related cultural and social trap in which on 35-year-old single, shop owner Niloofar (Sahar Dowlatshahi) finds herself that is the focus of Inversion.

Behnam Behzadi’s revealing slice-of-life family drama uses a panoramic image of the city obscured by smog as its establishing shot. The metaphorical title refers, in the first instance, to thermal inversion caused by warm air settling over cooler air that traps the harmful particles in the atmosphere close to the ground. But it is the intricately related cultural and social trap in which on 35-year-old single, shop owner Niloofar (Sahar Dowlatshahi) finds herself that is the focus of Inversion.

There are good days and bad days for Niloofar’s elderly mother, Mahin (Shirin Yazdanbakhsh), with whom she shares an apartment in Tehran. On days when there is thermal inversion Mahin cannot breathe. Mahin’s doctor advises her not to go out at all, but, like her independent daughter, she is stubborn and relishes her freedom.

What might surprise us in the first half of the film is how relatively familiar life in Tehran appears to be. Niloofar wears a headscarf, and her arms are covered, but she is comfortably dressed, often in trousers and wears make up. We never see her in a mosque or being encouraged to marry and have children. She drives herself to her thriving tailoring workshop where she employs a dozen workers and she does business with male suppliers and customers.

Although, like single thirty-something women in London Niloofar finds it difficult to meet eligible men, she is asked out to dinner by a good-looking, supportive man with a good sense of humour named Soheil (Ali Reza Aghakhani). It is clear from their romantic dinner that they both share a love of music and that the physical attraction is strong and mutual. While Niloofar shares her newfound happiness with her colleague and good friend Soudabeh (Setareh Pesyani) at work, she keeps her relationship with Soheil a secret from her family.

And then suddenly, the thermal inversion, literally, puts pressure on Niloofar, trapping her between her family responsibilities and loyalty and her independent, hard-earned lifestyle. When Mahin collapses from pollution and is ordered by her doctor to leave the city immediately, her older brother, sister and brother-in-law decide that the unattached, childless, female of the family should accompany their mother to a family property in the countryside.

Mahin feels guilty about imposing this move on her daughter, but there is no choice. Niloofar puts decides to move with her mother, but refuses to close her business. She decides to commute to the shop when needed while handing over the day-to-day management to Soudabeh. But the pressure intensifies when Niloofar discovers that behind her back, her family has sold her shop to pay off her (recently separated) brother Farhad’s (Ali Mosaffa, The Past) debts.

Mahin feels guilty about imposing this move on her daughter, but there is no choice. Niloofar puts decides to move with her mother, but refuses to close her business. She decides to commute to the shop when needed while handing over the day-to-day management to Soudabeh. But the pressure intensifies when Niloofar discovers that behind her back, her family has sold her shop to pay off her (recently separated) brother Farhad’s (Ali Mosaffa, The Past) debts.

When Niloofar discovers that Soheil has also been manipulative, keeping her in the dark about a piece of his past, she begins to feel surrounded by a conspiracy of men (although her jealous eldest sister is unsympathetic) determined to curtail her illusory freedom. The pressure of losing her home and friends in Tehran, her business and a chance at love through no fault of her own is too much and she decides to confront her family and then Soheil.

This quietly uplifting story of a woman’s courageous stand against her sexist culture is hardly subtle, but it is a non-didactic and satisfying critique against a society in which a female’s freedom is held hostage by the whims, needs and indulgences of brothers, fathers and husbands. While it is initially confusing to piece together the various family relationships, the camera cannot tear itself away from the lovely and charismatic actress Sahar Dowlatshahi. Like the actress Narges Rashidi who appeared in the marvellous Tehran-set political/horror film Under the Shadow (which was not in fact shot in Tehran), you could watch Dowlatshahi going about her business all day without being bored. She turns Niloofar into a real person, with her energy, compassion, determination, foibles, vulnerability and fighting spirit.

Paradoxically, while we are accustomed to seeing women in films set in the Middle East who lead lives we cannot imagine, there are probably a fair number of single, childless woman in the UK or in any Western, industrialised country who might find themselves with pressures and dilemmas similar to those Niloofar has to deal with. It is not just the smog that London and Tehran have in common, but the slow and slippery road to sexual equality.

You can watch the film trailer here: