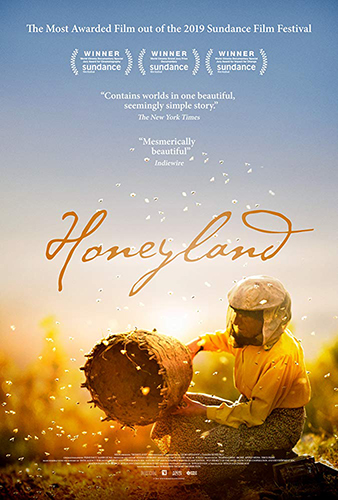

Joyce Glasser reviews Honeyland (September 13, 2019), Cert. 12A, 85 min.

Honeyland, a ravishingly beautiful documentary by co-directors Ljubomir Stefanov and Tamara Kotevska, demands patience like the bees kept by Hatidze Muratova but repays it with a rich and novel experience. Although the film is set in our times, 54-year-old single, childless, and all but toothless beekeeper Hatidze lives in a land that time forgot. Hatidze herself, however, is unforgettable as she maintains her humanity and her dignity when we could excuse her for losing it. Never sentimental, this small gem runs the emotional gamut from heart-wrenching to hilarious.

Hatidze shares a remote hut in an otherwise abandoned settlement in the Macedonian valley with her elderly, bed-ridden and half-blind mother Nazife Muratova, and their cat and dog. And then there are the bees hidden away behind rocks in the mountains and in the barks of trees that repay Hatidze’s loving care with the purest honey in the Skopje markets.

Hatidze shares a remote hut in an otherwise abandoned settlement in the Macedonian valley with her elderly, bed-ridden and half-blind mother Nazife Muratova, and their cat and dog. And then there are the bees hidden away behind rocks in the mountains and in the barks of trees that repay Hatidze’s loving care with the purest honey in the Skopje markets.

During the course of the film we pick up bits of biographical information from Hatidze, and though her age is impossible to guess, we learn that she was born in 1964 and never married. This is the only life she’s known. We see that she is good with children and would have liked to have had her own. The harshness of life has taken its toll on her appearance, and there is no one around to impress, but Hatidze is still determined to colour her hair, which is quite a ritual without running water.

Hatidze’s endearing relationship with her mother is one of the pleasures of the film. Hatidze is her mother’s carer and the 85-year-old is totally dependent on her daughter but is still self-aware and opinionated. When Hatidze is worried about her mother’s non-responsiveness, the elderly woman pipes up, ‘I’m not dying; I’m just making your life a misery.’ It is only at the end that we realise how much Hatidze, too, depends on her mother for her company and their shared past.

If there is no running water, there is no electricity, phone, or transportation either, and in winter Hatidze treks through the snow to a mountain side where, behind a stone, is the thick, golden honey that, in the film’s tear-inducing ending, she shares with her dog.

But long before this, we see Hatidze trekking alone to Skopje, the Macedonian capital, to sell her honey in jars. Throughout the film there are signs of modernity that seem jolting. We watch Hatidze bargain in Euros (and not Denar), and watch, with Hatidze, as a truck load of new neighbours move into an abandoned farm next door.

At first Hatidze welcomes the family with its cattle and seven young children. She is happy to have their company and is generous and kind. She spends time with the children, teaching them, playing with them and telling them stories, but for their parents, they are young farm workers. The children are put to work, with the parents almost comically oblivious to health and safety concerns.

The patriarch, Hussein Sam, and his wife betray Hatidze’s trust after she shows Hussein the secrets of her trade. Hussein is not a bad man, but when he tells a local businessman who is interested in his honey that the children are sources of cheap labour, we do not warm to him. Indeed, the Husseins show little interest in the children’s welfare, let alone in their education. The children are filthy and pretty much left on their own amid all the dangers of the farm. A toddler bursts out crying when it is covered in bee stings and a slightly older child is kicked by a cow in revenge for the child’s aggression. Some of the scenes offer a kind of black humour and we can laugh as, miraculously, everyone is still alive when the family move out at the onset of winter.

If Hussein does not come across as a good neighbour, he himself is pressured into providing larger amounts of honey to the local businessman than he should. While he tries his best to follow Hatidze’s advice of leaving half of the honey for the bees, commercial interests prevail, and he is too weak to hold out.

As the ancient sin of greed brings destruction, we find humour in Nazife’s surreal outbursts. When she learns from her distraught daughter what Hussein has done, she curses, ‘may god burn their livers,’ and God, in his way, appears to listen to these wonderful women.

The film becomes a metaphor for topical environmental issues western agriculture and for that matter, Brazilian. In microcosmic form, there is nothing short of tug of war going on between the drive for economic growth, a short-sighted government, the immediate demands of its citizens and the need for sustainability.

In Honeyland, we are not just reading about the negative effects of these issues on the native population like Hatidze, we are experiencing it. Hatidze is the last of her kind in the area and we are watching traditional practices, and values, die.

The directors are not heavy-handed about this topicality, and while the film is always thought-provoking, it never feels worthy or message laden. In any event, for the film’s short duration we are too absorbed in a totally different world to think about anything but a woman who might not know about women’s liberation but is one of the strongest and independent women you will see in any film this year.

You can watch the film trailer here: