Joyce Glasser reviews Cézanne – Portraits of a Life (Tuesday January 23, 2018)

Paul Cézanne, hardly a self-publicist, was 56 when the young art dealer Amboise Vollard gave him a solo show in Paris in 1895. But he had to wait another 122 years to have a solo exhibition of his portraits, which have received much less attention than his landscapes and still lives. Now, in a beautiful exhibition at London’s National Portrait Gallery (October 26, 2017-February 11, 2018), the portraits, 20% of his oeuvre, are in the spotlight. If you cannot make it to the exhibition, or even if you have seen it, Phil Grabsky’s terrific documentary Cézanne – Portraits of a Life is a must. The film is in selected cinemas in the UK on Tuesday 23 January 2018, as part of the Exhibition on Screen series.

When Pablo Picasso, who was also to be represented by Vollard, called Cézanne ‘the father of us all,’ the ‘us’ was painters. It took the public a while to understand why every painter since 1906 has been influenced by Cézanne. The Nabi painter Maurice Denis, in a rut in his mid-thirties, travelled to Aix in 1906 the year of Cézanne’s death to meet him. Before his pilgrimage, Denis was planning a large group canvas to be entitled Homage à Redon, as a token of his esteem for the great symbolist painter Odilon Redon. Upon his return from Aix, Denis painted a copy of a still life by Cézanne on Redon’s easel and the title was changed to Homage à Cézanne. Denis was hoping that he, and those immortalised in his painting, would be deemed modern painters by association.

Boy in a Red Waistcoat, 1888-90 by Paul Cézanne. National Gallery of Art, Washington. Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Paul Mellon, in Honor of the 50th Anniversary of the National Gallery of Art, 1995.47.5

Ridiculed and insulted in his native Aix-en-Provence until his death, Cézanne was a painter’s painter, a genius like Picasso who found a new way to see the world – and to see the friends, relatives, peasants and labourers who modelled for him. He only paid one professional model, an Italian boy named Michelangelo de Rosa, whom he painted four times. The best of the four is a large canvas on loan from the National Gallery of Art Washington where the exhibition travels after London. What makes The Boy in the Red Waistcoat (1888-90) so beguiling is how uncannily Cézanne captures an adolescent who has not entirely grown into his body or reached psychological maturity, despite a swagger and his nonchalant pose. His right arm sits on his hip, while his impossibly long left arm hangs down his body like another fold in blue drapery that seems to support him.

Also in the exhibition is a portrait of the artist’s son,‘little Paul’, that will remind you of Picasso’s portraits, a cross between his blue and his neo-classical stages.

Producer, Writer/Director Phil Grabsky, head of Seventh Art Productions, can be relied upon for guiding us through an exhibition and an artist’s life with articulate and erudite experts. He does not ask them to dumb-down. The result here is a fascinating art lesson that not only enhances the National Portrait Gallery (NPG) exhibition but provides the kind of insightful information that you wish were available from the rather stingy exhibition audio-guide.

Peppered through the visual gallery tour, original and archival footage and stills of Provence, and of Cézanne’s friends, family; family home (Jas de Buffan) and studio are segments with the experts, usually focusing on one painting or stylist advance.

The experts include: NPG Director Nicholas Cullinan and Senior Curator John Elderfield; the Musée D’Orsay’s Laurence des Cars and co-curator Xavier Rey; co-curator Mary Morton. We also hear from Philippe Cézanne, the artist’s great-grandson, the wonderfully descriptive Bruno Ely, Director of the Musée Granet in Aix-en-Provence and Denis Coutagne, head of the Paul Cézanne Society.

Self Portrait in a Bowler Hat, 1885-86 by Paul Cézanne. Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek, Copenhagen. Photo: Ole Haupt

Grabsky is, thank goodness, of the view that it cannot hurt to learn about an artist’s life, although Cézanne, who was intensely private, would have disagreed. The film is structured around letters written by Cézanne (voiced by Brian Cox) to his son, father, dealers, art critics, and to his friends. His closest correspondent is the writer Emile Zola, born in Aix just a year after Cézanne. There are also moving and enlightening letters from his friends (such a Monet and Pissarro) to one another or to Cézanne.

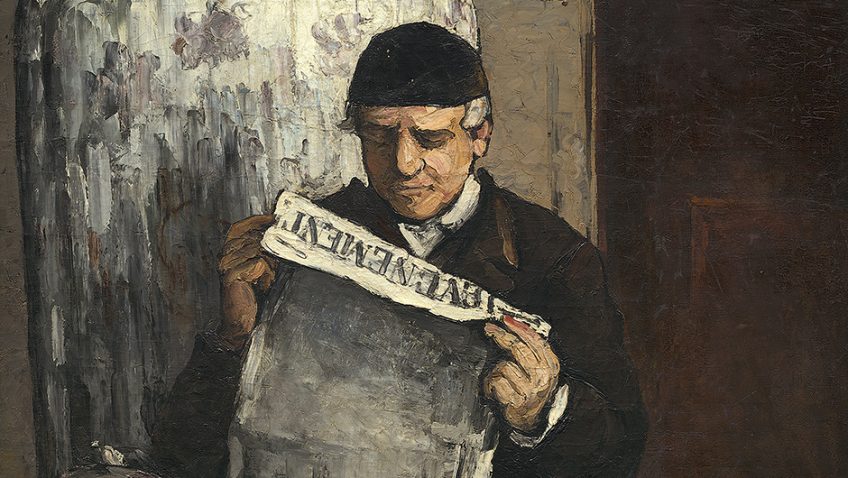

In 1866 the artist Guillemet wrote to Zola about Cézanne’s imposing, vertical portrait of the artist’s father Louis-Auguste (1866) that greets the visitor at the NPG. ‘He has the air of a Pope on his throne in a big armchair,’ wrote Guillemet, were it not for the newspaper he was reading. While Paul was disorganised, evasive, shy, literary and dreamy, Louis-Auguste, a self-made man, was, in Zola’s words, ‘bourgeois, cold, stingy and mocking’. But despite the difficult relationship between father and son, the portrait appears as a tender tribute to the man whose money enabled him to paint. A painting by Cézanne hangs behind the chair and the newspaper he is reading is L’Evénement, a radical paper that had published Zola’s defence of Cézanne.

Courtagne tells us how Louis-Auguste, a successful hatmaker who bought a bank, opened a letter addressed to Paul at the family home Jas de Bouffan, and learned that he was a grandfather. He said nothing to Paul, but cut off his allowance. It was Zola who stepped in, helping Cézanne financially from 1876-1886.

The artist also wrote (in later life via ‘little Paul’) to his long-time mistress and housekeeper turned-wife/mother/model – and housekeeper, Hortense Fiquet. She was Cézanne’s ‘Paris’ wife. Painting was his Aix, but never ex-wife, as he was travelling out to paint all day in nature until his death at 67. Hortense sat for Cézanne 17 times in the 1880s and moved house 22 times, but she also travelled with their son as we know from a lovely letter about a trip to Switzerland.

If the self-portraits (so dramatic with his palette knife application and then with his wide, diagonal brush strokes) are an exhibition within an exhibition, so are the many portraits of Hortense. John Elderfield tells us that ‘Cézanne was not interested in providing a great deal of information about the inner life of the people he was painting’, while Xavier Rey points out how Cézanne paints her in the revolutionary colour planes he was developing in his landscapes and moves her around in the pictorial space like the apples of a still life. The portrait is not the sitter, but the whole canvas, so compare Madame Cézanne in a Red Arm Chair with the paintings of Matisse in which textured background, foreground and sitters melt into one another.

For ticket information visit the website www.exhibitiononscreen.com

You can watch the film trailer here: