The BFI’s Reiner Werner Fassbinder Retrospective

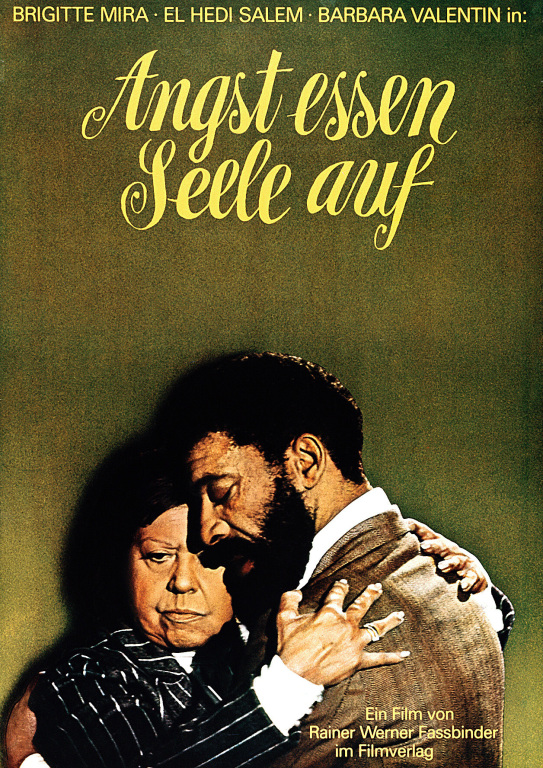

Joyce Glasser reviews Ali: Fear Eats the Soul (Angst essen Seele auf)

When the lights went up following a showing of Fear Eats the Soul at London’s BFI Southbank cinema, a group of silver-haired viewers, primarily women, did not stand up to leave. They wanted to talk about the film and did, until an apologetic usher entered the room. All of the women had seen the film in 1974 when they were in their 30s and had remembered it. This is not a film you can forget. Along with All That Heaven Allows, the 1955 Douglas Sirks’ film that inspired it, this is a film that speaks to our deepest and most universal emotions.

When Todd Haynes remade Sirks’ film in 2002 as Far from Heaven, he had the frustrated, affluent housewife fall in with a younger man who was not only of a lower class, but was black. Fassbinder got there first on the youth and race front, but to add an ironic dimension to his commentary on racism, and to heighten the pathos, he widens the age gap and closes the class divide.

When Todd Haynes remade Sirks’ film in 2002 as Far from Heaven, he had the frustrated, affluent housewife fall in with a younger man who was not only of a lower class, but was black. Fassbinder got there first on the youth and race front, but to add an ironic dimension to his commentary on racism, and to heighten the pathos, he widens the age gap and closes the class divide.

A ‘guest worker’ from a small town in Morocco who has been in Munich for two years, Ali (El Hedi ben Salem) is proud to be a car mechanic. His imposing body intimidates German men and attracts the very women who claim to be repulsed by North Africans, for everyone knows that they do not wash. Emmi Kurowski (Brigitte Mira) who has three selfish, narrow-minded, married children and is old enough to be Ali’s mother is ashamed to admit she is a cleaning lady. Both are working class, but Ali earns slightly more than she does.

The film is divided into two halves, divided by an off-screen holiday. In the first half, Emmi, an overweight, nondescript woman of around 60 takes refuge in a seedy bar to get out of the heavy rain. When she takes a seat at the first table she sees, Fassbinder’s trademark mixture of realism and stylisation is what hits you. A small, mixed-race crowd of youngish adults is clustered at the corner of the bar at the far end of the room. The shot is held for a long time while you feel the tension in the room and Emmi’s discomfort. The room is silent. Everyone is staring at Emmi.

Then the bleached blond-bar owner saunters over to the woman for her order. When Emmi tells the bar maid/owner that she has always been attracted to the Arab music when she passes the bar, the group, as a joke, urge Ali to ask the woman to dance. After the dance, Ali, troubled by the prank, insists on walking Emmi home.

The development of the relationship between Ali and Emmi is always plausible and natural; sometimes romantic and intentionally predictable. In the first half Emmi and Ali’s happiness is almost instantly shattered by prejudice and Fassbinder’s catalogues the various forms racism can take. The local shop keeper pretends he does not understand Ali who has a limited vocabulary and speaks in sentences that consist of a noun and a verb. When Emmi presents Ali to her children, instead of a handshake, there is a chilling silence that ends when her son smashes the TV set.

The television episode – one of many references to All That Heaven Allows – parallels the scene where Jane Wyman’s offspring present her with a television.

Whether Ali looks at Emmi as a mother figure or is attracted to her kindness, humility and non-judgmental deportment, we do not know. It is not a matter of sex, as Ali has all the women he can handle. The bar owner temps him with couscous (which Emmi dislikes and refuses to cook) – and her bed for the night whenever he wants.

What binds them is that they are both lonely (Emmi’s three children never come to visit and she does not seem to have friends) and have endured prejudice (Emmi’s parents disowned her for marrying a Polish worker). Both are also insecure. When Emmi confesses that she feels afraid of her happiness, Ali warns her that ‘fear eats the soul’. But it is Ali who collapses with a perforated stomach ulcer. A doctor informs her, ‘It happens to a lot of foreign workers. It’s the stress.’

In the second half of the film Fassbinder (who plays Emmi’s lazy, hot-headed son-in-law) shows how the relationship develops once society becomes accustomed to the couple, or when they start to realise their hostility is impractical. The shopkeeper’s wife realises they have lost a good customer and puts her husband on the charm offensive, while a nasty neighbour becomes friendly after Emmi offers to give the neighbour space in her basement. One of Emmi’s sons comes by to reimburse her for the TV while asking if she could babysit. Emmi is more relieved than offended.

When Emmi’s work colleagues decide to involve Emmi in their bid for increased wages, Emmi goes along with their decision to shun an estranged Czech worker, new to the job. And when Emmi invites the neighbours in, she encourages them to feel Ali’s muscles as though he were an animal. Emmi might be different from the average working class 1970s German, but she is no crusader.

It’s not just the great acting, script and moving love story that make Fear Eats the Soul so compelling. The film is a treat for the eyes, with its 1970s fashion, décor and with its symbolism. In one scene when the couple are at the breakfast table after their first argument, we notice a bad painting of three stallions behind Ali, while a painting of a stormy sea hangs behind Emmi.

Check the BFI website for lectures about Fassbinder’s contribution to cinema history and for the schedule of films in the retrospective. These include his adaptation of Theodor Fontane’s 1896 masterpiece of poetic social realism, Effi Briest and The Bitter Tears of Petra von Kant, with an all female cast. Melodrama continues with Martha, based loosely on a short story by Cornell Woolrich whose stories inspired many filmmakers, including François Truffaut and Alfred Hitchcock. And this Saturday there is a rare opportunity to see World on a Wire, Fassbinder’s 1973 television miniseries about a cybernetics engineer who begins to suspect that our world exists within another.