Joyce Glasser reviews The Teachers’ Lounge (April 12, 2024) Cert 12A, 99 mins. In cinemas (This review may contain a spoiler)

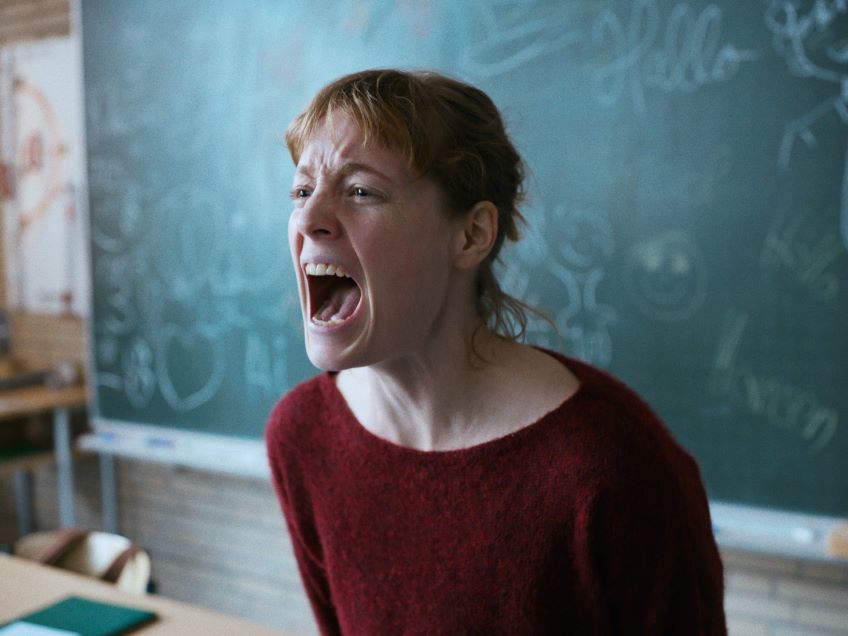

German Director and co-writer (with Johannes Duncker) Ilker Çatak (I Was, I Am, I Will Be) went to High School in Germany and Turkey and though his memories are happy ones, The Teachers’ Lounge is both autobiographical and topical. Schools today are microcosms of society where arriving at the truth is complicated by an inability to get everyone to accept the same truth. Çatak’s tense, riveting drama lands dedicated teacher Carla Nowak (a terrific Leonie Benesch) in a juicy moral dilemma, then undermines its heroine in an off-putting ending.

Carla is in control of a largely obedient class of mixed sexes, races, ethnicities and aptitudes. The problem she puts before the class is whether 0.999 is the same as 1. The point of the lesson is to introduce the class to the mathematical proof. They learn that a proof is a deductive argument showing that the given assumptions logically guarantee the conclusion. The problem is also a metaphor for the film because Carla cannot guarantee the truth of what appears to be an evident conclusion.

As Carla, a new maths and PE teacher, settles in to her job she learns the high school is plagued by a spate of mysterious thefts. Faculty members inform the student reps that they have to put a stop to it, but their means are questionable. Carla is uncomfortable when two teachers ask the reps to make a list of suspicious classmates and when, in her classroom, girls are ordered to leave and boys to remain and put their wallets on their desks.

Two of the teachers suspect Ali (Can Rodenbostel) in whose wallet they find a large amount of cash. They do not believe his story that he was going to buy a computer game after school and the principal calls in Ali’s parents who confer amongst themselves in Turkish. They are offended when they are asked to speak German and verify Ali’s reason for having the money.

Perhaps because Carla is self-conscious about speaking Polish with a Polish speaking colleague at the school, she is sensitive to the situation and concerned that Ali’s father’s employment came up in the conversation.

Dissatisfied at the school’s approach to identifying the thief, after informing the staff that she believes Ali is telling the truth, Carla, who has her own suspicions, decides to identify the real culprit.

Her simple plan involves using her own wallet inside a jacket pocket as bait. She puts the jacket on the back of her seat in the teachers’ lounge in view of her laptop with a video camera pointed at the jacket pocket. The camera can see nothing else, so wider issues of illicit filming are relevant only in principle. Returning to the lounge and watching the playback, Carla is shocked to see the unmistakable, distinctive patterned blouse sleeve of a staff member reaching into her jacket pocket.

Carla assumes that a quiet, private word with the thief will suffice. If she returns the money and promises to put an end to the crimes, that will be the end of the matter. But the suspect is outraged at the accusation, forcing Carla to escalate the complaint to the principal who, after seeing the video, reports it to the police. Unfortunately, the accused’s son Oskar (Leo Stettnissch), the brightest boy in Carla’s class, is caught in the cross hairs with conflicting loyalties.

Caught in a web of half-truths, innuendos and misunderstandings, Carla’s determination to do the right thing ends up making matters worse. And she does make a series of strange decisions, for example, being drawn into questions about the theft in an interview by the school newspaper.

Çatak’s ability to create suspense is admirable, but his real triumph is turning the viewer into a participant in the moral quagmire, forcing us to think at every turn.

The problem is not that the film presents us with pretty solid proof of the culprit’s identity and then wants us to accept there is room for doubt. The problem is that Çatak and Johannes, whose idea the ending was, seem to have their moral compasses out of whack.

In the production notes, Çatak justifies the final scene: ‘I see it as…a plea for resistance, that one must not let the system get you down. What Oskar is doing is admirable …I wanted to grant him an exit.’ This is astonishing when, in the film’s most dramatic scene, Oskar physically attacks a sympathetic female teacher, nearly taking out her eye, and destroys her personal property, refusing to apologise. What the audience want is not for Oskar to have a triumphant exit but to learn a lesson.