Joyce Glasser reviews I am Belfast (April 8, 2016)

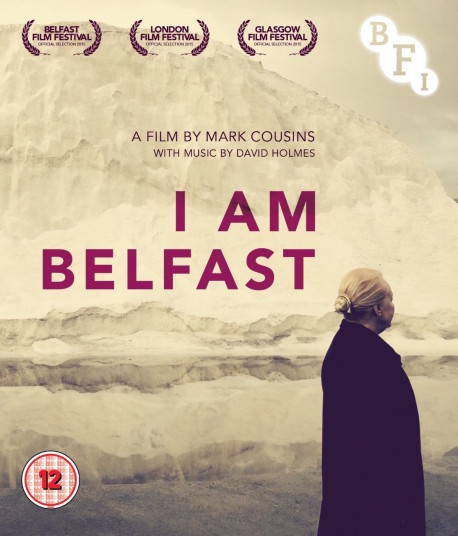

Mark Cousins narrating his epic documentary series, The History of Film: An Odyssey is an often perceptive and fascinating, sometimes irritating and notably subjective exploration of international cinema from one who knows and loves the medium. Cousins’ latest, theatrical, documentary, I am Belfast has a bit of the Odyssey in it, too, as Belfast’s Prodigal Son returns from his adoptive home in Edinburgh after a long absence to revisit the city of his formative years.

The Penelope he finds awaiting him weaves a meandering story that could well have kept suitors at bay for a decade. Now it’s our turn to hear it. For Cousins is guided – as Dante is guided by Virgil and Beatrice – by a mystical 10,000-year-old woman (Helena Bereen) who is the personification of Belfast. Together they travel through the streets of his native city in a dreamlike reverie mixing verbal metaphor with visual footage and specific references to past people and events.

The woman says, ‘When I look at myself I see colour’ and the camera shows us some graffiti, coloured walls and houses with autumn leaves. There is then a reference to Van Gogh and ‘this is a colour study,’ referring to a nondescript corner of an unidentified street. We hear her say, ‘So much of what I am is a stage or a frame,’ and the camera focuses on a tunnel and a large, freestanding metal door-like frame to a factory. So far, Belfast looks like any run down city.

The woman says, ‘When I look at myself I see colour’ and the camera shows us some graffiti, coloured walls and houses with autumn leaves. There is then a reference to Van Gogh and ‘this is a colour study,’ referring to a nondescript corner of an unidentified street. We hear her say, ‘So much of what I am is a stage or a frame,’ and the camera focuses on a tunnel and a large, freestanding metal door-like frame to a factory. So far, Belfast looks like any run down city.

The woman wants to stress that the natural character of the people from Belfast is caring, not combative. People stop to help a man lying on the steps of a building. Two ladies who have a bit too much to drink amuse us (for a minute) with their candid, but actually rather mindless, banter.

When we have some facts and information to anchor us, the film fares better, but these moments are almost all centred on the Troubles. I jotted down the following passage that is uttered with no context or explanation: ‘Salt and sweet, Nationalist and Unionist, salt and sweet forced one another apart. The largest enforced movement of people since WWII.’

There is one interesting story that is touchingly told against the background of the actual site of McGurk’s Bar, which is now a trompe l’oeil painting of Mr McGurk at the entrance to the bar. Even, here, however, the story is incomplete. We are told that on 4 December 1971 the Ulster Volunteer Force bombed McGurk’s a bar frequented by Irish Catholics nationalists.

There is one interesting story that is touchingly told against the background of the actual site of McGurk’s Bar, which is now a trompe l’oeil painting of Mr McGurk at the entrance to the bar. Even, here, however, the story is incomplete. We are told that on 4 December 1971 the Ulster Volunteer Force bombed McGurk’s a bar frequented by Irish Catholics nationalists.

Fifteen people were killed and seventeen wounded (all Catholic). Among the dead were Patrick McGurk’s wife and 12-year-old daughter. He was seriously wounded, but went on television to plead that there be no retaliation (regrettably, his moving statement is not read or replayed). What is not specifically stated was that retaliation had begun almost instantly and was to make1972 the bloodiest year of the troubles.

Despite the occasional tangible facts and visits to the historic docks for a few minutes with the Titanic and to an historic coop store, now closed, I am Belfast sinks under the weight of its rhetorical pomposity. Cousins seems to forget the audience, particularly given the demographics of his target audience, who come away from the film knowing almost nothing about Belfast that they had not already known.

The concept of Belfast personified as an old woman grows so tiresome that you wonder why Cousins felt the need to delegate his task of personalising his visit home. Most people would prefer to hear Cousins’ talk about his childhood in Belfast than watch, for example, a baffling mock funeral of a bigot named Hale that ends the film.

There is little explanation for non-locals that Leslie Hale was a Belfast preacher who allegedly – he denied it – owned a Rolls Royce and a private Jet. He moved to Tampa Florida to preach, and raise funds, on television. One has to assume he is the object of the ‘funeral of a bigot.’

Along with the paucity of information, we are shown mainly derelict buildings as our narrator obsesses on paint chipping off neglected old buildings. But Belfast has several interesting 20th century, 29 museums and galleries (of varying degrees of interest) and historic buildings that are in use. The political conflict has even left an artistic legacy that has been turned into the unique and informative Belfast Murals Tour. Sadly, our tour with the old woman does not cover these.