Ammonite (March 26, on BFI iPlayer and digital outlets) Cert 15, 120 mins.

Francis Lee’s God’s Own Country might have been a pale, self-conscious, and heavy-handed imitation of Brokeback Mountain, but it garnered enough attention for Lee to cast in this new film, Ammonite, two of the world’s greatest actresses. Kate Winslet is early 19th century geologist, palaeontologist and fossil dealer Mary Anning, and Saoirse Ronan is her friend and lifelong supporter Charlotte Murchison. They portray their respective characters admirably but by superimposing the template of God’s Own Country onto Mary Anning’s remarkable life, Lee does both women a disservice.

Ammonite eschews a cradle-to-grave biography, dispensing with arguably the most interesting years of Mary’s career, which, despite her lack of education and the harsh life of working-class women, was remarkable. When the film begins, Mary is in her forties (she died aged 48) and lives with her elderly mother Molly (Gemma Jones, the knowing granny in God’s Own Country) in a small house behind their fossil shop. One older brother who would accompany Mary and their father on his fossil outings, survived her, but is not part of Lee’s female-centric story.

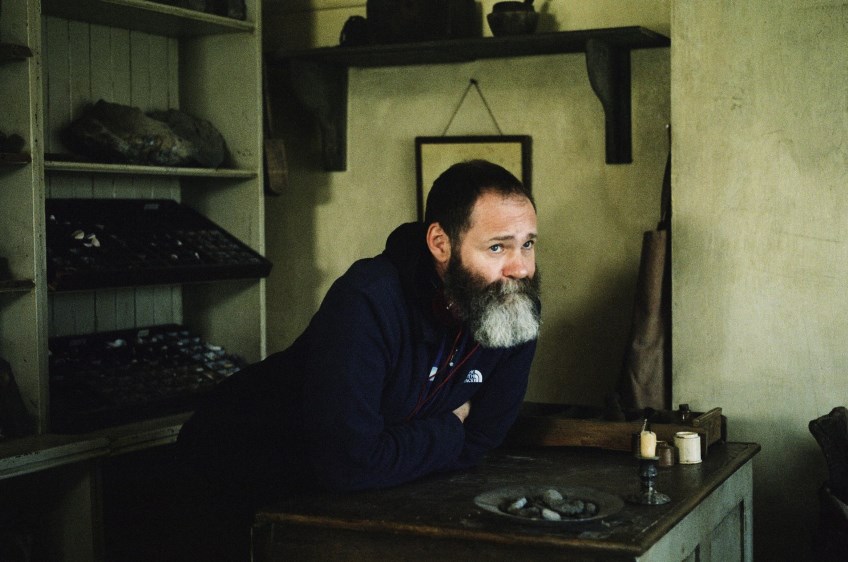

Unconcerned with her looks and dressed in unflattering, informal dresses, Mary runs the shop while receiving occasional visits from scientists and amateurs who would pay their respects as her achievements were recognised by 1840. In earlier days she led excursions to the fossil rich Blue Lias and Charmouth Mudstone cliffs.

When we first see Mary, she is returning from the nearby beach covered in mud. The best time to find fossils is in winter when the mud slides erode and open the cliffs, but you have to be quick and know the tides, or the fossils will wash out to sea. It is dangerous work, but in Lyme Regis alone, Mary, and, for a time, her collecting partner, Elizabeth Philpot (Fiona Shaw) made this activity their vocation and living.

A gloomy Molly puts two bowls of gruel and an egg, which is rotten, on the table. Like Molly, Lee’s Mary is a woman of few words and no nonsense. The cottage behind the shop is a spartan, joyless place.

Though poor, Mary is proud, greeting the wealthy Londoner Roderick Murchison (James McArdle) with a dismissive curtness, warning that she no longer gives tours. (In real life she met Roderick and Charlotte Murchison in her twenties when she did give tours). Murchison reassures her he is not a tourist, but a scientist, and will compensate her well. What Murchison really wants is to get his “bright, funny, clever wife back” because since their wedding Charlotte has not been herself. As we see from their intimate scenes together, the problem might be him.

Murchison decides to leave Charlotte behind in their comfortable hotel and offers Mary money she cannot refuse to take Charlotte fossil hunting. This, along with therapeutic dips in the sea in a bathing machine, which had become popular from the mid-18th century, is designed to cure her melancholia.

Winslet plays Mary as a withdrawn, repressed woman who cannot hide her annoyance. But she is a businesswoman, too. Soon after accepting the job, however, Charlotte collapses at Mary’s front door with a high temperature and Doctor Lieberson (Alec Secareanu, co-star of God’s Own Country) is aggrieved when neither Mary nor Molly offer to nurse her back to health. Eventually, fearing Charlotte might die, Mary overrules Molly and agrees to take on the task.

As in God’s Own Country, Lee turns the women’s relationship into a graphic, passionate same-sex love story, in which both women find a release from claustrophobic societal mores. Not everything is rosy though. Perhaps it is Mary’s bitterness about being left out of the male-only Geographical Society that heightens her resolve not to lose this last chance at love.

When Dr Lieberson invites Mary and Charlotte to a concert at his home, Mary, portrayed as uncomfortable around people and antisocial, prefers not to attend. Charlotte, all dressed up, radiant and thrilled at a bit of culture, chats with Elizabeth Philpot in the front row, while dowdy Mary, sulks in the back row and leaves early.

Mary’s long anticipated visit to London to be reunited with Charlotte some time later goes badly due to Charlotte’s naïve misreading of her mentor. The real Mary Anning did visit Charlotte at the Murchison’s grand home in London, but when she was 29 and the visit was apparently a success. For nearly two decades, Charlotte promoted Mary’s work on her many foreign expeditions with her husband.

But for Lee history must be revisited with the assumption that spinsters were really closet lesbians. As a result, the film is less about a self-taught scientist’s craving for the professional recognition she deserved, than about her craving for love. Aside from two scenes at the British Museum where crowds admire one of Mary’s early uncredited fossils, we learn almost nothing about her many important scientific discoveries. In this, the film resembles The Dig where an invented love-triangle masks the contribution of Sutton Hoo’s only female archaeologist, Peggy Piggot.

The celebrated partnership of Anning and Philpot is commemorated in Tracy Chevalier’s novel, Remarkable Creatures and Lee takes it for granted their fossil finding was coupled with love making. But Philpot lived in a “women’s” (low ceilinged) house with her two unmarried sisters, considered poor marriage prospects for various reasons) all her adult life. Were all three lesbians, or just independent fossil hunters of some repute who developed a medicinal balm (Philpot’s Salt) that they made and distributed?

It is true that Mary never married and had children, but it is not surprising when her father died young and exhausted; nine of her ten siblings never reached adulthood,and a husband could have prevented her from pursuing her vocation.

A husband might object not only because of the physical dangers and improprieties, but because of Mary’s friendships with prominent men. Though conspicuously excluded from the film, these included the wealthy collector James Birch, who saved her from bankruptcy by auctioning his collection – comprised mainly of Mary’s discoveries – and her admirer, the esteemed palaeontologist Sir Henry De La Beche, who marketed lithographic prints of his famous sketch, A More Ancient Dorset for her benefit. Later in her life, the theologian and palaeontologist William Buckland persuaded the government to grant Mary a lifetime annuity for her contribution to British science.