The title of the thought-provoking documentary Point and Shoot refers as much to pointing a camera and shooting video footage as it does to pointing at a target and shooting an M-16 assault rifle or M240 machine gun. In fact, Point and Shoot is a documentary within a documentary and both raise interesting questions about how cameras shape events as opposed to records them.

Filmmaker Marshall Curry (Mistaken for Strangers) is the credited director, but the subject of his documentary, Matt VanDyke, is the producer and cinematographer of almost all of the incredible footage we see.

Aside from being afflicted with OCD, VanDyke’s story is not particularly unusual until he reaches the age of 27. An only child growing up on a diet of action movies in suburban Maryland, Vandyke was loved, coddled and spoiled by his doting (single) mother and grandmother, and then by his steadfast girlfriend, Lauren. He was well-educated, but never had a real job and had never done his own laundry. Then one day he saw an Australian TV programme about a dashing adventurer seeker and ladies’ man who recorded his own exploits on camera. VanDyke decided to embark on what he calls his own ‘a crash course in manhood’.

VanDyke took a course in photography, and with the alias of Max Hunter, set out on what was to become a three-year, 35,000 mile solo motorcycle trek across Northern Africa learning how to film his adventures. The footage is incredible, and part of you wants to be on the back of that motorcycle. As he drives to Afghanistan he tells us that, ‘over time, I think I grew into the image I presented on camera.’

He drove through Iran dressed as an Afghan, was beaten in Kabul, visited the former house of Osama bin Laden and spent time with US soldiers, imbedded as a journalist. Then VanDyke met Nuri, a pacifist Libyan hippy, who invited him to Libya to visit him. Bribing an official to gain entry, VanDyke, who never had friends in America, became close with Nuri and all of his friends.

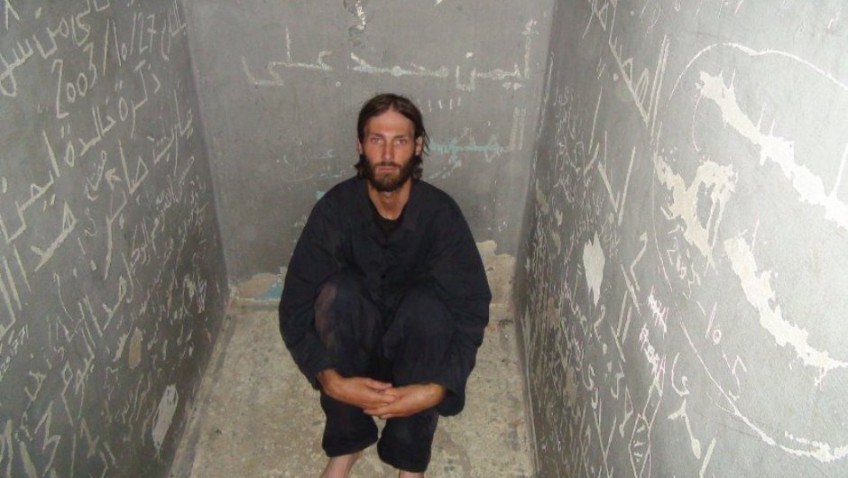

Shortly after VanDyke returned to Maryland in 2010, the Arab Spring had reached Libya. He could not sit in front of TV watching ‘his friends’ being killed and set off to join the revolution in Libya. Smuggled into Benghazi from Cairo, like a Special Ops hero, he met up with Nuri and their friends. ‘This time, I was in a war zone as a participant,’ VanDyke states. Ambushed by Gaddafi’s men in Sirte, VanDyke was wounded, beaten and hauled off to a Libyan prison. He spent nearly half a year in solitary confinement, sharing a cell with insects, filth, and faeces. By the time he was freed by rebel troops, the tide of the revolution had changed. Urged to return home, VanDyke put on the uniform Nuri gave him and seemed delighted to notice that he had become a celebrity in Libya and on CNN.

With the war over, and victory celebrations complete, Van Dyke returned home to Lauren and his mother. At the end of his five year ‘crash course in manhood’ a tall, handsome 31-year-old Matt VanDyke is being interviewed by the director. He still wonders whether the crash course worked and so do we. Has VanDyke become a reality TV hero or a man who will pitch in at home and earn a living? He also wonders whether he was successful in affecting effects, or merely documenting them as an outsider.

Now, somewhere in Libya, Nuri might be asking the same thing. Since VanDyke departed, triumphant, the vacuum left by the loss of Gaddafi and the absence of a replacement government has been filled by Islamic extremists. Libya is used as a new route for drug and arms smuggling and human trafficking. Now, Islamist militants pose a threat that is every bit as great as Gaddafi to Nuri and his increasingly unusual moral values.

Joyce Glasser – MT film reviewer