Joyce Glasser reviews Lost in Karastan (January 22, 2016)

Ben Hopkins (The Nine Lives of Tomas Katz, Simon Magus) is one of the few British Directors who did not look west to Hollywood or New York, but east, first to Berlin where he lives, and then to Turkey.

There he made his 2006 documentary, 37 Uses for a Dead Sheep and became one of the first filmmakers to go inside the formerly nomadic Pamir Kirghiz tribe as they adapt to their new home in Turkey. He stayed in Turkey for to shoot his excellent 2010 feature film, The Market: A Tale of Trade, a witty and well-timed parable about the dual nature of Capitalism.

In addition to winning awards at the Ghent and Locarno film festivals, The Market was the first film in 64 years written and directed by a foreigner to win an award at the Antalya Gold Orange Film Festival.

It is, for this reason hard to resist thinking that Hopkins’s latest film, Lost in Karastan is, if not autobiographical, then certainly inspired by Hopkins’ experience filming in out of the way locations and appearing on the festival circuit.

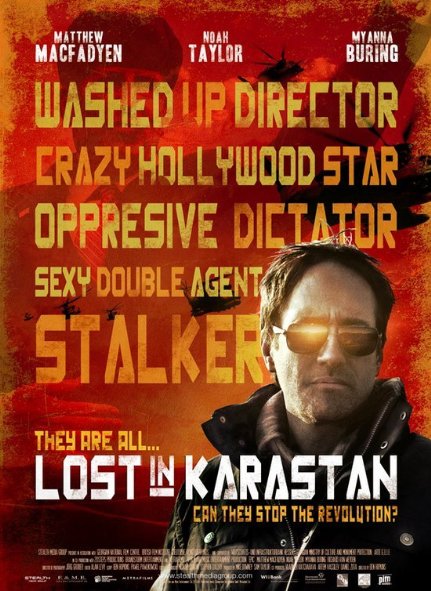

Forty-something, bachelor Emil Forester (Matthew Macfadyen), an art house auteur with a fading cult following is in a rut. He shares his Swiss Cottage apartment with his dog and the occasional visit of a housekeeper whom he cannot afford to pay.

Forty-something, bachelor Emil Forester (Matthew Macfadyen), an art house auteur with a fading cult following is in a rut. He shares his Swiss Cottage apartment with his dog and the occasional visit of a housekeeper whom he cannot afford to pay.

That he has a housekeeper, despite living alone and being skint tells us something about Emil. One day out of the blue he receives a call from the Palchik International Film Festival, inviting him to attend a retrospective of his 3.5 films.

We then hear the publicity: the autonomous Republic of Karastan: a land of mountains, lakes, hardworking people, a stable government – a land of inspiration. This is just what Emil needs, as he lives his dog in the care of the housekeeper.

Naturally, mountains aside, the truth is somewhat different, and the first half of the film chronicles Emil’s surreal, off-putting, if not scary, experiences in Palchik, the capital of this newly formed so-called Republic, governed by shady ‘President’ Abashiliev, educated at the ‘Royal College of Holloway’.

Unbeknown to Emil, Abashiliev is fending off a revolt, which explains the tanks Emil has noticed. He offers Emil unlimited access to the country’s resources and unlimited funds to make a film about a 14th century Karastanian folk-hero.

What washed-up filmmaker could resist such an offer? Abashiliev, we learn, wants to claim this hero as his ancestor in order to reassure the population of his dubious legitimacy.

Emil’s one link to sanity is the beautiful festival organiser Chulpan (Macfadyen’s co-star in Ripper Street), but here, too, nothing is as it seems. Chulpan appears to be Abashiliev’s mistress and Emil suspects that her affections for him are not sincere.

The absurd, the surreal, strong atmosphere, exotic locations and the sense of people existing in an unstable and hostile world are trademarks of Hopkins’ films that are all present in Lost in Karastan.

Hopkins makes the most of his location shooting in Georgia, with buildings and landscapes from the Black Sea town of Batumi, Tbilisi, the former cultural capital of Eastern Europe and Tkibuli, a coal mining centre. Particularly effective are the dystopian shots of Batumi housing where Emil’s presence attracts a hostile crowd.

What is less successful, is the script, which is all the more surprising as is it co-written with Pawel Pawlikowski (The Last Resort) whose 2013 film, Ida, won the Oscar for Best Foreign Film. Macfadyen conveys the insecurity of a man who gradually comprehends that he is a pawn in a lethal game that he does not understand.

He realises that his film is a sham and he cannot trust anyone. But in a situation and character driven film, what is sorely missing is any sense of character development. We remain largely indifferent as to Emil’s fate.

The romance between Chulpan and Emil is too underwritten to be very unconvincing, but perhaps the biggest misfire is Noah Taylor as Xan Butler, the resident actor whom Emil is forced to use in the film. Taylor (Lara Croft: Tomb Raider), who was so perfect as the eponymous Simon Magus in Hopkins’ enchanting 1998 debut feature, is allowed to overact to the point of embarrassment.

But the fundamental problem is the mix of tones that fail to marry. We are given a mix of black comedy that is half social satire, on the model of Borat: Cultural Learnings of America for Make Benefit Glorious Nation of Kazakhstan (which the first half resembles) and half horror film, as Berberian Sound Studio or Barton Fink.

In both of those films a lonely man who works in the film industry (sound designer and writer respectively) thinks he has been offered the answer to his problems when he is invited to a faraway location to work on a film, only to find he is out of his depth.

In Borat, the disconcerting scene in which children have been invited to a screening of Emil’s The Line of Infinity, an 18-rated adult film, might have gotten laughs, but here, it is truly unsettling and part of Emil’s nightmare.