Joyce Glasser reveiwsThe Black Panthers: Vanguards of the Revolution

Director/Producer/Writer Stanley Nelson has done the world a great service in The Black Panthers: Vanguards of the Revolution. The Black Panther Party (BPP) played a crucial role in the raising of black consciousness and in the civil rights movement, but sorting out the history of the movement is a pretty daunting task.

Fortunately, Emmy Award winning Nelson has done the hard work for us and has delivered an engrossing, dramatic narrative, albeit with a bias in favour of the organisation and, understandably, significant omissions.

Combining fascinating archival footage with a particularly articulate and compelling array of interviewees, many of whom are former BPP members, Nelson takes us back to its roots in Oakland California. In 1966 Bobby Seale and college student Huey Newton started the Black Panther Party for Self-Defence to resist police brutality and the racially-motivated killing of innocent black people.

With the Vietnam War and draft in mind, beleaguered young black men felt: ‘if we’re going to fight, we may as well fight in our cities.’ The BPP had a ten point plan that included freedom, safe housing, good education and a halt to police brutality and rule by Capitalism. Inundated with calls for new chapters across the country the party could not always screen the membership to determine who was joining.

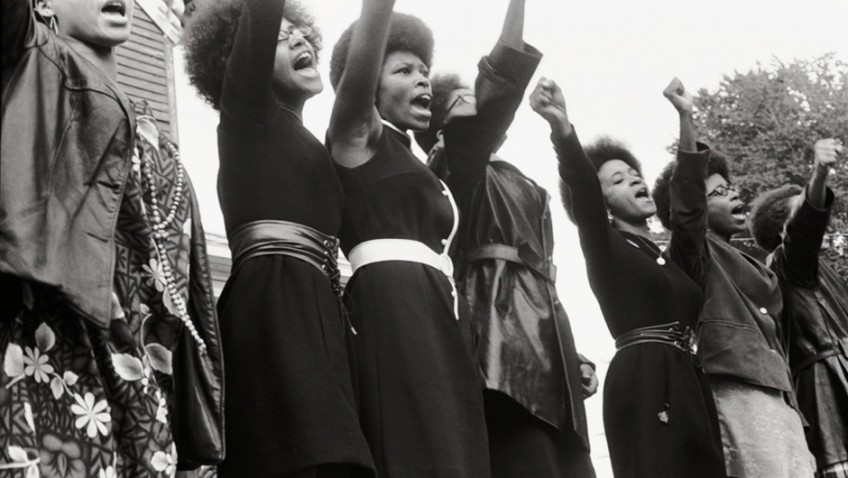

In Oakland and other cities the Panthers established breakfast programmes for black school children to give them a fair start. There was even a newspaper, where the police ‘pig’ was born under the caustic pen of the movement’s ‘Minister of Culture,’ the graphic artist Emory Douglas. Image, in the form of a dress code, was also important in raising awareness. The group’s gun-toting swagger, black leather jackets and black berets attracted the media as well as young white people and became known as radical chic.

Individuals and specific incidents on both sides of the BPP/ Government divide meant that the BPP was not only misrepresented, but misunderstood and maligned. Nelson shows Minister of Information Eldridge Cleaver challenging Ronald Reagan to a duel, and only half joking about battering him to death. This kind of aggression fuelled the twisted agenda of J Edgar Hoover who convinced President Nixon that the BPP was ‘public enemy number 1.’ Hoover’s true colours were unfurled in his malicious dirty-tricks campaign to destroy the  organisation.

organisation.

As we see from early archive footage, the BPP, that ran self-defence patrols, used guns against armed police if it were deemed justified. One such confrontation between police and Panthers resulted in the death of a police officer and the wounding and arrest of Huey Newton. The limited evidence, combined with Newton’s treatment while in prison, became the basis of a widespread ‘Free Huey’ campaign that the Panthers turned into a cause célèbre. Newton became a media celebrity when his conviction of Voluntary Manslaughter was overturned.

Bobby Seale (who ran for Mayor of Oakland in 1973) was another living martyr. He was charged with conspiracy and inciting to riot in 1968 and imprisoned as part of the Chicago 8 trial, in which he was shown bound and gagged in court. This caused outrage and a welcome media frenzy. The evidence was thin enough for the Chicago 8 to become the Chicago 7.

Innocence was not always so easy to establish. As a reaction to the assassination of Martin Luther King, Eldridge Cleaver initiated an ambush on police officers in Oakland. Two were wounded, as was Cleaver, but 17-year-old activist Bobby Hutton was shot dead. Cleaver claimed Hutton was shot 12 times after surrendering. Hutton became a national symbol of police brutality and racism and we see Marlon Brando speaking (‘that could have been my son’) at Hutton’s funeral.

Cleaver fled the country, receiving a warm welcome in Cuba until Castro learned that the BPP had been infiltrated by the FBI. Cleaver and his wife Kathleen, who had been Communications Secretary in the BPP and became an author, lawyer, and academic, then went to Algeria. Eldridge returned to America in 1975 only to became born again Christian and conservative Republican. He died of cancer at age 62.

Nelson is particularly explicit about how J Edgar Hoover used all the forces at his disposal to discredit the movement and cripple its leaders. He created an ultimately fatal wedge between Newton and Cleaver (who did not help matters) and struck a blow at party membership by infiltrating the party until no one felt safe.

The FBI was behind the cold blooded murder of the talented communicator and Chairman of the Chicago branch, Fred Hampton, who had a knack for building coalitions with disenfranchised white groups and Latinos. One by one the promising leaders were neutralised until the party closed in 1982 with only 27 members.

This well-researched and well-made film is essential viewing for anyone interested in racial politics, black history or American history. Even with a 115 minute running time, Nelson had to be selective in what he chose to portray, so this is not a definitive or even entirely objective version of the story.

One aspect of the BPP that Nelson had no time to mention is the list of publications and professional accomplishments of the party leaders – both women and men – whose true potential was only partly realised by their involvement in the Party.