Joyce Glasser reviews Elvis (June 24, 2022) Cert 12A, 160 mins.

After the Freddie Mercury biopic, Bohemian Rhapsody and the Elton John biopic, Rocketman, comes Elvis, Baz Luhrmann’s (The Great Gatsby, Moulin Rouge) biopic of the Elvis who needs no surname. Elvis matches its predecessors’ in energy and epic scale, but lacks their sense of fun, drama and focus on the music. The ambitious cradle to grave story, narrated by Presley’s slippery manager, Colonel Tom Parker (Tom Hanks) has Luhrmann connecting the dots with frenetic pacing rather than filling in the canvas with emotional substance, depth and the sordid physicality of the King’s slow demise.

Colonel Tom Parker is the film’s unreliable narrator, and he is neither a real Colonel, nor a Tom nor a Parker. He was a carnival barker. Nor did this carnie, who is, in the 1930s, featuring country western music acts like Hank Snow (David Wenham) have an ear for music. Unfortunately, we gain as few insights into Parker as we do into Elvis.

In short, Parker’s an opportunist who was at the right place at the right time, telling a vulnerable dirt poor talent, eager to buy his mother a house, what he wants to hear. Parker tells us, ‘I am the man who gave the world Elvis Presley. But there are those who would make me out to be the great villain of the story.’

Flashback to Elvis (Chaydon Jay), who spends the first thirteen years of his life in a black neighbourhood in Tupelo, Mississippi, experiencing the frenzied singing and dancing in the Pentecostal revival tents, and then moves to Memphis, Tennessee, where he imbibes country music, fusing it with African-American rhythm and blues. By 1954, Presley (now played by Austin Butler) is recording with former DJ turned record producer Sam Phillips, who is sowing the seeds of rock and roll and lets amateurs of any background – like Otis Redding – record at his studio.

Parker first hears about the 19-year-old’s capacity to draw crowds from Hank Smith’s son, Jimmie Rodgers Snow (Kodi Smit-McPhee, wasted) as Elvis is arriving at the Louisiana Hayride, with fellow band members guitarist Scotty Moore and bassist Bill Black. Parker tells Jimmie, ‘they aren’t putting a coloured boy on the Hay Wagon?’

The scene in which Parker, lurching in the shadows, first sees Presley on stage – and the reaction of the audience – is terrific. Here is his dream: a white boy who sounds and moves like he’s black and is causing gay boys and straight girls to swoon while their mothers pretend to disapprove.

The middle section races along like a fairy tale. Parker promises Elvis the moon and the Presley family attribute Elvis’s meteoric rise – a cat-and-mouse game between the censorious local governments and police and Elvis’s determination to express himself – to Parker. Parker realises that Elvis is “forbidden fruit” and the more fuss that is made of his scandalous movements, the more tickets are sold.

As the film makes clear, Elvis is very close to his mother, Gladys (Helen Thomson) whose only child is all the more precious for being a surviving twin. Perhaps her smothering love is what he looks for on stage, and perhaps Gladys’ early death of a heart attack when Presley is on military service in Germany is the result of the strains of separation. When Elvis departs on his first road trip with Parker, he reassures her that the whole celebrity thing, as his spineless father Vernon (Richard Roxburgh) predicts, ‘will probably be over in a flash.’ But Gladys is more worried that the hungry crowds ‘will come between us.’

In an interesting bit of dialogue we learn that Parker’s carnie act, Hank Smith, has allowed Elvis to record and perform all his songs on the condition that there are no “gyrations.” Along the way we see how Elvis sings the provocative Hound Dog after seeing Sister Rosetta Tharpe’s (Yola) perform it, and that he picks up moves from Little Richard (Alton Mason) and advice from his friend BB King (Kelvin Harrison Jr), with whom he hangs out on Beale Street in Memphis. The Beale Street scene is a montage, glossed over with a bit of dialogue rather than dramatized conversations.

Two white, Jewish, Northerners, Jerry Leiber and Mike Stoller, wrote Hound Dog, and went on to write four other songs, including Jailhouse Rock for Presley, but they are not mentioned. Nor is there any other mention of where his songs came from, what Presley added to the songs in the recording studio or why he didn’t take up BB King’s advice to start his own label.

The purchase of Graceland (Elvis delivers on his promise to his mother); Presley being carted off to do military service in Germany at the height of his fame in lieu of going to jail; his meeting and marriage to Priscilla (Olivia Dejonge), the daughter of an army officer, are rushed through in a series of montages. It is Elvis’s movie career that dominates the 1960s, when his corny movies like Blue Hawaii (competing with Psycho, Dr Strangelove, A Fist Full of Dollars, Lawrence of Arabia, The Misfits etc) leave him exhausted and demoralised. The soundtrack albums fail to register on the charts. We never experience Presley’s depression and the toll on his marriage.

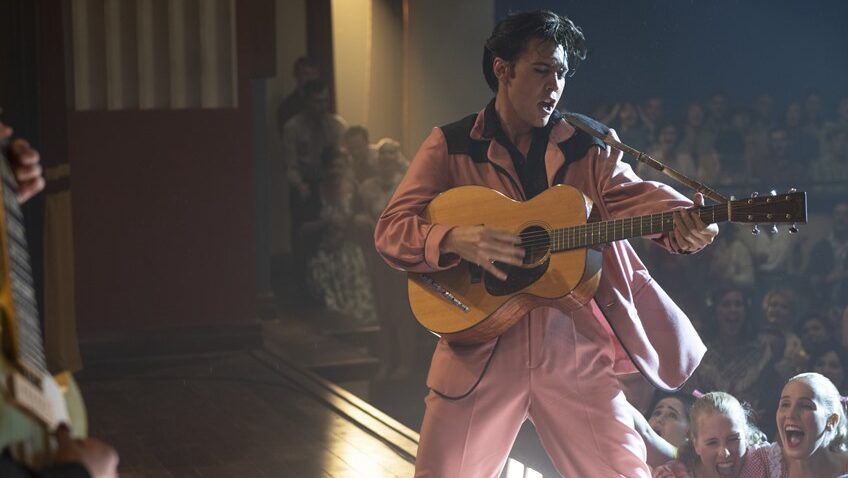

Parker thinks up a sponsored television Christmas special to re-launch Presley’s sagging career. Much is made of the tension between the divergent approach of Elvis’s young, hip producer, Steve Binder (Dacre Montgomery) and Colonel Tom’s obligations to the sponsors. Elvis oozes sexuality in his 1968 Comeback Special, playing his guitar in tight, black leather, to a small crowd, and it relaunches his record career. But the happiness is short lived and not only because, due to Parker’s immigration status, Elvis cannot tour abroad. Behind his back and counting on his Business Manager father, Vernon’s ignorance, Parker locks Elvis into a gruelling, long term contract in Vegas, a deal that will write off Parker’s gambling debts. Not known for his subtlety, Luhrmann stages an insistent performance of Caught in a Trap when we learn that Presley does not have enough money to buy out Parker.

Austin Butler is terrific: he looks like Elvis and moves, sings and lip-syncs (all the Vegas songs are the originals) impressively, but there’s no time for him to display the acting that wowed audiences who saw him on stage in The Iceman Cometh on Broadway opposite Denzel Washington. The fat suit and the heavy makeup fail to convey how fat, sick and pathetic the real Elvis was during his last years, performing non-stop in Vegas. His dependence on the drugs that killed him to keep up the merciless routine and combat his unhappiness after Priscilla leaves, are barely mentioned, perhaps to secure a 12A rating. It is Luhrmann who is caught in a trap. Elvis is a tragedy, one that Luhrmann, who directed Romeo and Juliet, recognises, but cannot bring to life.