Joyce Glasser reviews Hallelujah: Leonard Cohen, A Journey, A Song (September 16, 2022) Cert 12A, 118 Mins.

Today it is hard to find a singer who hasn’t covered some version of Leonard Cohen’s song Hallelujah, or an occasion at which it has not been solemnly played. But in 1984, the album on which it featured, Various Positions, was rejected by Columbia’s new CEO Walter Yetnikoff, one of the rare instances where an album that was already paid for was not released. As the title promises, Hallelujah: Leonard Cohen, A Journey, A Song is about that iconic song and how it managed to be revenged through our love of music. Though it’s a treat for Cohen fans, the film tends to depart from its remit, losing its narrow focus, if not our interest.

So we tend to get the salient points of Cohen’s life to put the song in context and learn that he was born into a wealthy orthodox Jewish family and that he retained ties to his synagogue throughout his life. His father died when he was 9, although we hear less about his mother, whose love of singing was contagious.

No biopic of Cohen can omit his late and dramatic start in the world of music after graduating from university and publishing his first book of poems. Dissatisfied with his writing (the early 1960s in Hydra were covered in the 2019 documentary Marianne and Leonard: Words of Love) in 1966 Cohen decides to try his hand as a folk singer-songwriter. He had written published poems and a novel, and had written a song, Suzanne, but did not know if it was a song. He asked Judy Collins who played the song and told him she was going to record it. It was a hit.

Then she famously invited him to sing it at a fundraiser where Jimi Hendrix, among others, would be performing. He balked and walked off the stage. Collins dragged him back where, with Collins also singing, he finished it to great acclaim. Despite being strange and “old” (he was over 30) he was subsequently signed to Columbia records.

We find out that the Suzanne in that song was not related to the Suzanne he later married and with whom he had two children. But we never hear about Marianne, about whom Cohen wrote three of his best known songs. We are however, introduced to fashion photographer Dominque Isserman of whom Cohen says, ‘I was fifty when I first fell in love.’ They met on Hydra. She was living with him when he was working on Hallelujah, but asked about its meaning, refers us to Larry ‘Ratso’ Sloman (a music journalist).

The filmmakers centre the narrative around a 1992 coffee chat between ‘Ratso’ and Cohen. ‘Ratso’ is a Cohen expert, but this thread can be distracting. So too are other choices, such as the diversion to talk about his unfortunate experience with Phil Spector. Spector used his wall of sound in 1977’s album Death of a Ladies Man, of which Cohen said, ‘Tina Turner should have sung it.’

It is a while before we focus on Hallelujah, understandably. It is hard to talk about that song without talking about Cohen’s religious life and his lifelong quest for spiritual meaning. But do we have to spend so long hearing once again about Cohen’s six years on a zen retreat on Mount Baldy?

In terms of his spiritual quest, Cohen claims to be a man of discipline, but he’s also a creative writer and a man. A commenter adds, “it’s in his work that he reconciles those deep conflicts.” Few songs exhibit that dichotomy as clearly as Hallelujah. In that respect it might have been more interesting, if less visual, to see how the religious words in Cohen’s original were transformed into the hit version by John Cale. What was lost and what gained?

It’s when we get to John Lissauer that the trail turns hot. Cohen and Lissauer, though younger than Cohen, hit it off and, at Cohen’s suggestion, booked rooms at the Chateau Marmont in LA to collaborate on some songs if not an album. Cohen said he had to go somewhere and disappeared for eight years.

When he returned, they wrote Hallelujah, or the version that was rejected by Yetnikoff. Lissauer was more or less blacklisted in the industry over the debacle. The music producer Hal Willner fared better as did Cohen, who, close friends say, maintained his confidence. The album was later published by a tiny label with no fanfare. It was a disappointment, but Cohen could go on. Lissauer had to wait. In 2019 he was inducted into the Grammy Hall of Fame.

A documentary about this song might have examined Walt Yetnikoff who, at CBS records, launched the careers of dozens of famous artists, championing their cause. The “tone deaf”’ record head’s change of personality and increasingly violent temper around the time he was promoted to CEO of Columbia in 1975 has been written about and might be germane to this story.

Once we get to 1991 and the idea of asking John Cale to appear in a Cohen tribute concert, the film turns thrilling. Cale had heard Cohen sing it at the Beacon a few years earlier ‘and it blew me sideways,’ he recalls.

The filmmakers postulate that the route to the song’s success was (i) Cale, (ii) Jeff Buckley and (iii) Shrek. The film is at its best when they examine these somewhat overlapping stages in detail. We learn for example, that co-director Vicky Jenson had to find the music for a particularly contemplative and emotional scene in Shrek.

Being a Cohen fan she thought of Cale’s Hallelujah, but though he had reduced it to pop hit length, she needed it reduced to two minutes and all the sexy bits removed.

Meanwhile, Rufus Wainwright had a contract with Dreamworks to sing the song, but Jenson thought his voice too young for the sequence. The compromise was that Jeff Buckley’s voice is in the film and Wainwright’s on the best-selling soundtrack album.

From the moment we hear a bit of Cale until the end of the film, you will marvel (Bob Dylan’s cover and the hilarious anecdote about his meeting with Cohen in Paris); you will cry (Jeff Buckley who sang the song like an angel but never wanted Cohen to hear it); and you will laugh (when the song proves a guaranteed hit for various stars of American Idol and The Voice). Despite the sexy bits, Yolanda Adams sang the song at the Covid-19 remembrance service in Washington DC).

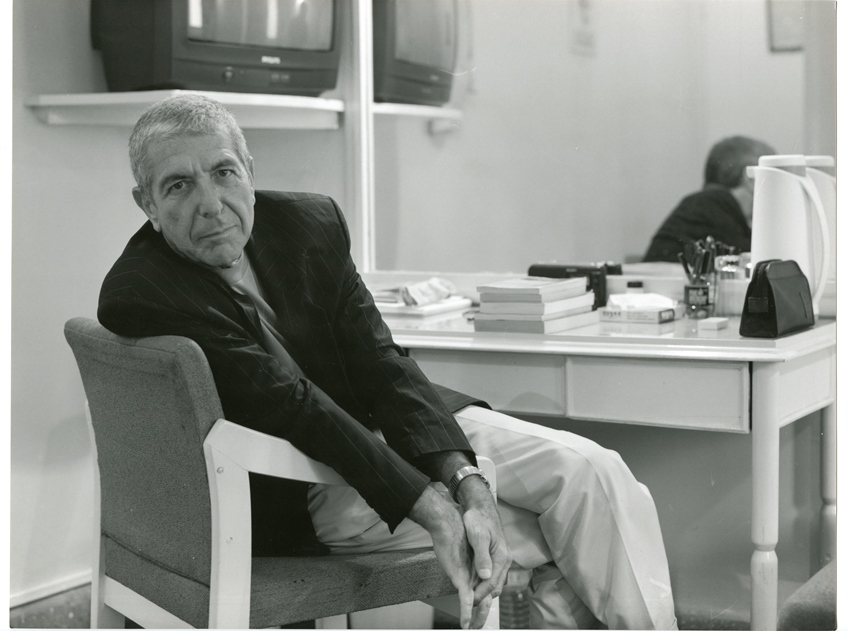

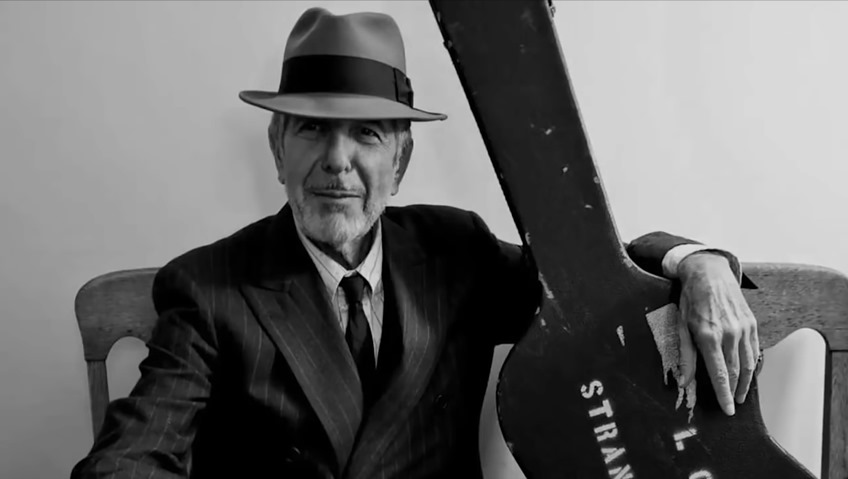

But no one performs Hallelujah like Cohen, obliged to return to the stage after a 15 year absence due to his manager’s fraud. His return was a giant hallelujah. There are few cities where the septuagenarian who wanted to be “a Hebrew elder” did not perform, often falling to his knees, closing his eyes and chanting the lyrics of Hallelujah like no one before or after him ever could.