Hope Gap (playing in cinemas and on Curzon Home Cinema from August 28, 2020) Cert. 12A, 100 mins.

William Nicholson has had a long and successful career as a novelist and writer, with two Academy Award nominations (for Gladiator, which he co-wrote and for the 1993 film adaptation of his play Shadowlands), but has only directed one of his scripts, the largely forgotten Firelight. There was, perhaps, no one else who could have directed Hope Gap, an adaptation of Nicholson’s autobiographical play, The Retreat from Moscow, about a young man caught in the middle of his parents’ painful divorce. Though marred by an excess of literary and symbolic allusions and the questionable casting of Annette Bening, it is a perceptive and moving depiction of the hurtful end of a bad marriage that lasted too long.

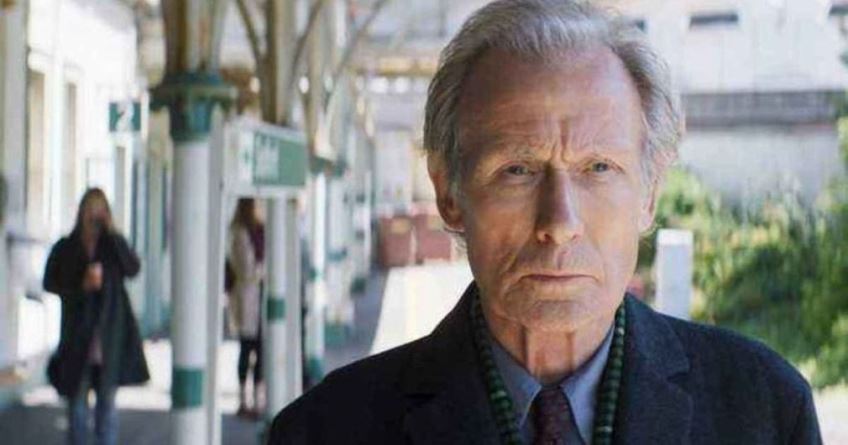

Jamie (Josh O’Connor, God’s Own Country), enjoyed an idyllic childhood in Seaford, Sussex with Grace, his gregarious, poetry-reciting, Roman Catholic mother (Annette Bening, Film Stars Don’t Die in Liverpool) and Edward (Bill Nighy, Love Actually), his quiet, history teacher father. In an expository introductory voice over which almost derails the film at the start, the camera shows us exactly what Jamie’s voiceover is telling us. You can almost feel Alfred Hitchcock turning over in his grave. Jamie remembers his mother on the beach, watching him explore the tide pools, but never asked what she was thinking or whether she was happy: “you don’t, do you?”

When we first meet Grace, she is taking that nostalgic walk to Hope Gap. Passing by a man untangling a large kite or small glider plane, she chirps, ‘”a lonely impulse of delight”, eh Garry’ and then, like a school mam, informs him that the line is by WB Yeats. Although Grace later tells her husband she has not done the walk for ages, Garry says, ‘Oh, it’s you Grace’ as though they meet every day, and Grace does not stop to catch up, although they are on a first name basis.

Grace is not exactly a bundle of good cheer, as some viewers might recognise the line from the poem An Irish Airman Foresees his Death, written in memorium to the son of Yeats’ friend Lady (Augusta) Gregory. Then again, neither is Edward, who walks around their tired, but comfortable, sprawling seaside home as if sedated, obsessed with his gory Wikipedia entry on Napoleon’s retreat from Moscow.

When Edward returns home from work, we sense both the familiarity of years of marriage, and the boredom of their routine in a scene about a cup of tea. Edward makes his own without offering Grace one. When Grace protests, he notes that she already has a cup. She says it’s cold, although it is only half empty.

‘Why don’t you ever finish your tea?’ he asks, (can this be the first time in nearly 30 years of marriage that he’s been curious about this?). Grace replies, ‘I suppose because I don’t want things to end’.

This weighty line is one that works better on stage than in a film where every gesture and line is magnified. It is a brilliant punchline, as it is not only in keeping with Grace’s character (a Catholic, she believes a marriage vow is forever, and a long marriage cannot just be discarded), but it is also prescient. Yet you cannot help but feel that the dialogue around it was written for this striking riposte.

From a symbolic cup of tea, Grace’s thoughts turn to their only son and she reflects out loud on how much she misses him, as though he were the tragic airman. Now a thoughtful, compassionate computer programmer in London, Jamie’s close work colleagues fear that he is “unreachable” while his mother has her own theories about his status as a bachelor in a basic flat big enough for one.

Grace complains that Jamie never visits, never suspecting that she might be the reason, while Edward claims, “he has his own life.” For the past year, it turns out, Edward has had his own life, too, and in some brilliantly written and acted scenes, we are the uncomfortable voyeurs of Edward’s long overdue endgame.

When Edward surprises Grace with the good news that Jamie is coming for the weekend, only Edward knows it is step one in his own retreat strategy. Railroaded, Jamie’s life becomes consumed by the revelation that the happy marriage he took for granted had died years ago. Used by Edward to buffer the blow to Grace, Grace clings to Jamie in her denial, suicidal self-pity, and bitterness.

We are treated to light relief when Grace buys a puppy, names it Eddy and teaches it to roll over and play dead. The film is always on the verge of turning to melodrama as Jamie comes to terms with the situation by supporting his mother in her depression and eventual reawakening.

Nicholson is a master at blending his themes into his dialogue. In Edward’s college lecture, his students debate the morality of the retreating French soldiers who took the clothes off the dying to prolong their own lives. Asked why she took Edward, his lover Angela (Sally Rogers) answers, ‘I think I thought there were three unhappy people and now there’s only one.’

This line suggests why the play was more aptly entitled, The Retreat from Moscow, a title too metaphorical for a film, perhaps, which is replaced with the metaphorical Hope Gap, more a theme than a place. Right until the bitter end when there is no chance of victory, Grace clings to the hope of reconciliation that Edward and Jamie know is impossible. While Angela’s self-righteous, reserved demeanour, prematurely dowdy appearance and depressing bungalow (loads of cups of tea) says more about Edward’s character than Grace’s, it is hard to imagine how this couple stayed together as long as they did.

That this prevarication is Edward’s source of guilt, not his decision to leave adds more depth to his character and makes Grace somewhat more sympathetic. While Bill Nighy is perfect casting and O’Connor is impressive in an awkward role as a half-baked character, it may strike you that Bening was chosen with an eye on the box office. Since her accent does not quite work, we keep expecting a line or two about how this staunch English teacher met a gregarious American ten years his junior, but we only learn that they met when, literally, he got on the wrong bus.

There is enough sincerity and depth in this candid story of a late life marital breakdown to keep you watching, but Grace’s endless poetry reading is more pretentious than powerful, and leads to a cringeworthy ending.