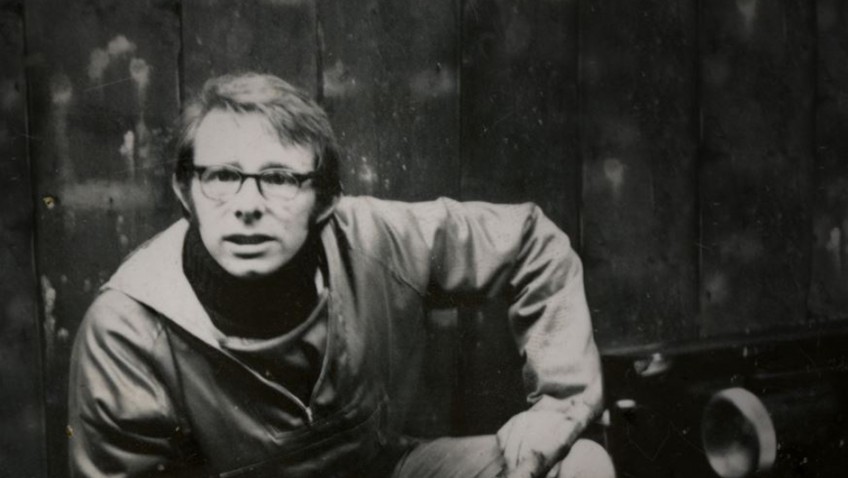

Joyce Glasser reviews Versus: The Life and Films of Ken Loach (June 3, 2016)

Call it serendipity or a well calculated bet, but there’s no doubt that interest in Versus: The Life and Films of Ken Loach will be bolstered by the announcement, on 22 May, that Loach won the Palme D’Or at Cannes for his latest film, I Daniel Blake. A early birthday present (Loach turns 80 on 17th June), Loach’s second Palme D’Or winner (after the Wind that Shakes the Barley) is a typically hard-hitting criticism of the welfare system.

While Louise Osmond’s (The Dark Horse, Richard III: The King in the Car Park) film does what it says on the tin, that image is unfortunately apt. For this workmanlike documentary is a processed, homogenised tribute to a filmmaker who is remarkable for his shelf life alone. Filmmaking is a part of Loach’s DNA. One of the film’s few revelations is that during a particularly low point in his career, Loach resorted to making commercials, for at least he was behind a camera. He sheepishly admits to compromising his anti-capitalist principles by making a commercial for McDonald’s.

Osmond gathers a number of high profile talking heads (including Cillian Murphy, Gabriel Byrne and director Alan Parker) to panegyrize their friend, colleague, director, father, husband, in the usual manner. No one, least of all Loach himself, however, says anything that would make the 6 o’clock news. Loach’s account of the car accident that killed his five-year-old son is very moving, although it is an isolated, tragic fact that sheds no light on anything that follows.

The most interesting part of the film is when Loach talks about the filmmaking process, illustrated by clips. This is nicely done when Loach focuses on first-time actor, 14-year-old Dai Bradley’s speech before the class in Kes and how he achieves that unaffected acting that is a hallmark of his social realist style. But relatively few of the films are explored in a way that shed light on his filmmaking which we already know to be unconventional. Loach primarily shoots in chronological order to avoid reminding actors where they are emotionally and physically in the story, and they often have no idea where the story is going until the day of the shoot.

Actor and producer Tony Garnett (who collaborated with Loach for thirteen years) talks about the early days at a rapidly expanding BBC, which provided ‘working class ruffians like us’ with jobs. They were asked to make single dramas, in-studio ‘in a class-ridden society’. Loach and Garnett wanted to make dramas on location about working class people facing real problems in life and ‘having sex and enjoying it.’

The documentary singles out the positive reaction and the social impact of their courageous film, Cathy Come Home (1966), about a young mother (played by Carol White) whose children are taken away from her by social services when their father falls on hard times. Loach makes a point of telling us that White went to Hollywood on the back of her stellar performances in this and Poor Cow, only to be swallowed up by the system, leading to drug abuse and an early death. He does not mention the fate of David Bradley, however, who, after winning the BAFTA for Best New Comer for Kes, had a frustrating career in the UK film industry, a career that dried up completely by the early 1980s.

Given the fact that Loach, like Woody Allen, has been making films for over 50 years, it would be impossible to do justice to the film side of the ‘life and films’ claim of the title. We already know that, in one of cinema’s most long-term and remarkable collaborations, Paul Laverty has written almost all of Loach’s films since Carla’s Song in 1996. Their collaboration is glossed over, but it’s clear that they share the same political views. Loach vents his political views in his films and Loach’s family and friends all claim that there is a marked difference between the mild-mannered, quiet father and friend and the dangerous subversive revolutionary on a film set.

That being said, Osmond does not seem keen to explore Loach’s leftist socialist political life even when he begs the question by observing that he came from a conservative background, and went to Oxford. While it is one thing to criticise a system that fails working people who fall on hard times, it’s another to start a new political party (Left Unity), support Julian Assange and boycotts of Israel, none of which activity is mentioned in the film.

Another controversy that involves Loach’s views of Israel, however, is recounted in some detail. Loach was the director of the late Jim Allen’s play Perdition based on an actual trial (Rudolf Kastner, of Budapest Aid, was acquitted by Israeli’s Supreme Court). The play recreates a mock trial, asking whether saving some Jews for repatriation to Israel in exchange for sacrificing others to the gas chambers was in fact a Zionist collaboration with the Nazis. Loach has harsh words against The Royal Court’s Max Stafford Clarke for bowing to pressure and cancelling the production.

Also omitted is Loach’s statement that it would be pointless to screen I Daniel Blake, for the conservative government because ‘punishing the poor is part of the prime minister’s project’. Preaching to the converted seems equally pointless, however, particularly as Loach says that he came out of retirement when Cameron was elected to make I, Daniel Blake. Perhaps Osmond’s refusal to be as controversial in the documentary as Loach is in his films has something to do with the documentary’s producer, Rebecca O’Brien. She is Loach’s partner in Sweet Sixteen Films and has produced most of his films since Hidden Agenda in 1990.

You can watch the film trailer for here: